While doing preliminary research on Berlin’s Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum, we came across the amazing artworks of Larissa Fassler, a Canadian artist living in Berlin. Her works are inspired by everyday life in cities and focus on perceptions, patterns and human behaviour within the built environment. She uses traditional architectural instruments such as drawings, models and maps, but adds anthropologic layers and personal impressions to them. The results are fascinating cityscapes that combine the hardware and software of a city: a mapped aggregation of the actions and perceptions of the users within the architecture they inhabit. She also worked on Kottbusser Tor and the Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum, which has been subject to our 5-day workshop in Berlin.

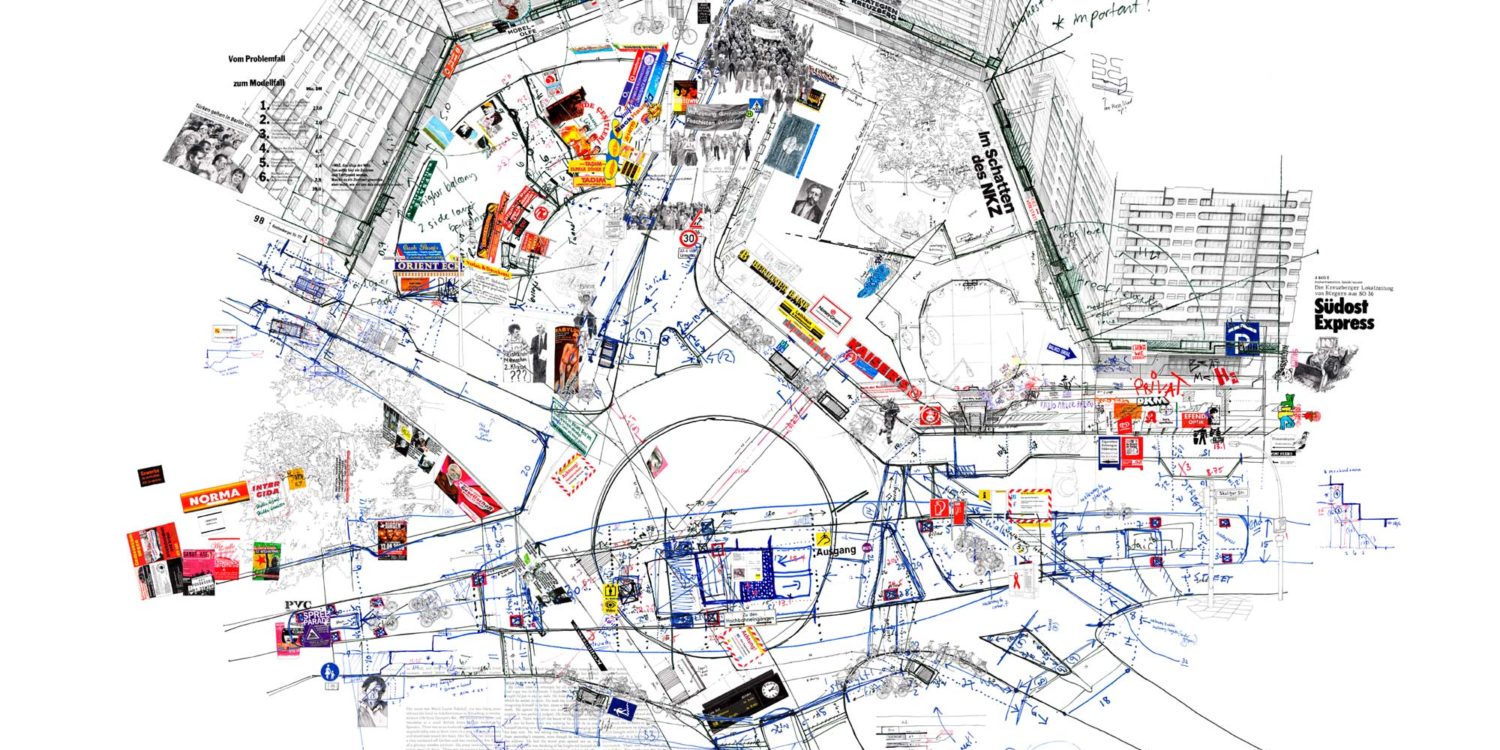

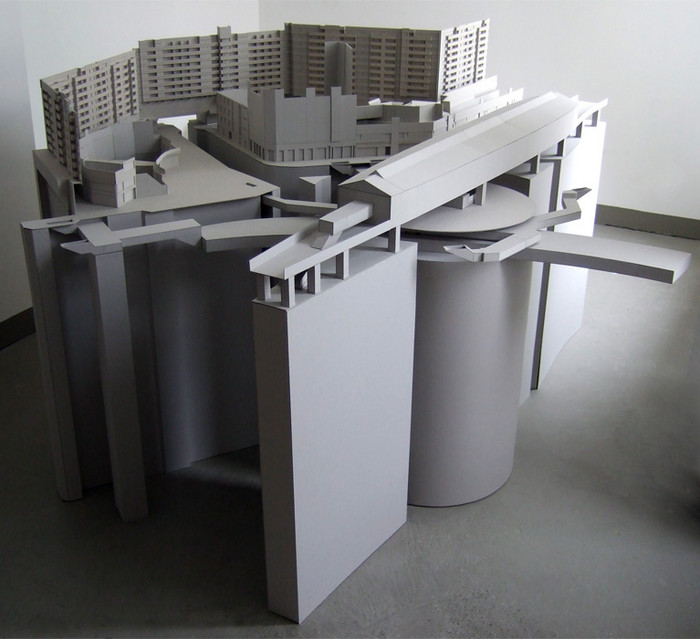

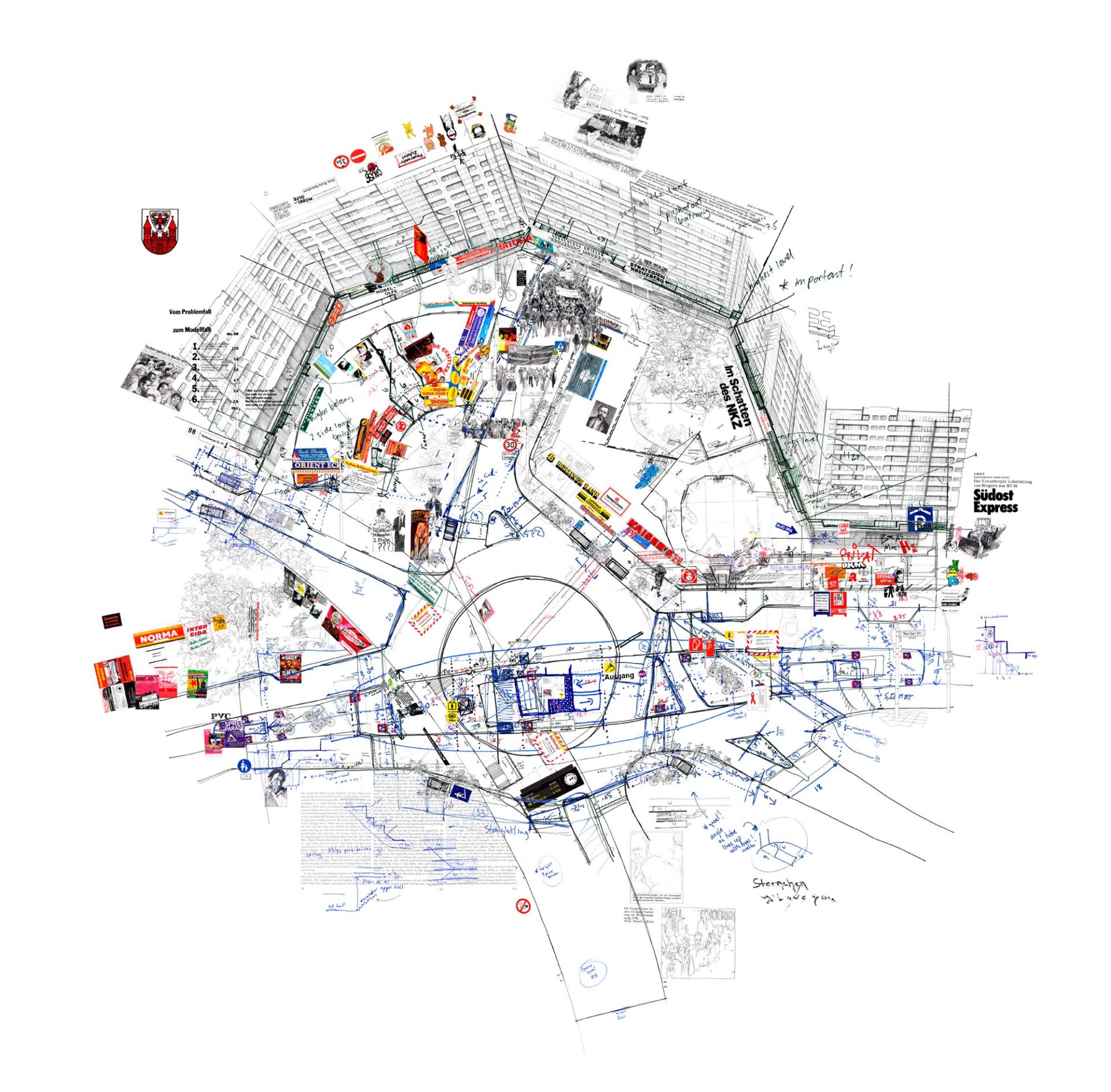

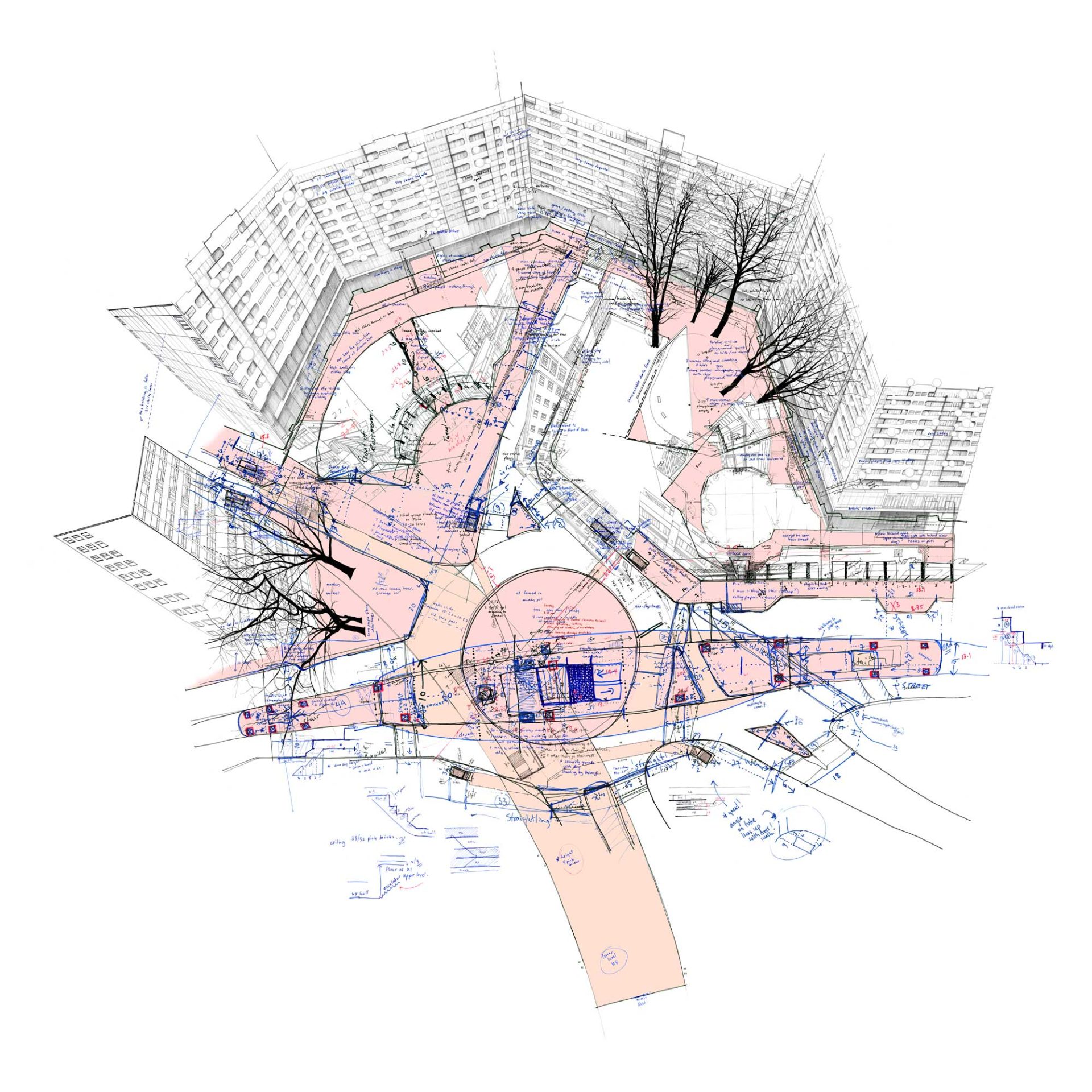

“Kotti” is one of her works, consisting of a scaled model and drawings. The scaled model is a representation of the publicly accessible spaces of the NKZ and its surrounding area. The cartography drawings include a wide variety of information, from the number of people crossing and the places were people urinate to the current weather and the locations of the food stalls. It seems to be a combination of mind mapping, community mapping, and ethnographic research.

We wanted to know more about Larissa’s inspirations, impressions and ideas regarding Kottbusser Tor and the Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum, and she has been so kind to answer some questions.

MM: You have made artworks of other places before working on Kottbusser Tor. What triggered you about Kotti that made you want to get into it and make art pieces on it?

LF: Before beginning work on my sculpture and subsequent drawings of Kotti, I had done two other pieces focusing on urban architecture. The first Hallesches Tor and the second Alexanderplatz are both works that are based on underground sites. At that time I was interested in looking at the subterranean spaces of cities that contain public life. In 2004 I moved to Kreuzberg not far from Kottbusser Tor and ‘Kotti’ became a place that I used and passed through daily over a period of years. This over-scaled, monolithic concrete structure, an amphitheatre-like space, held such a clash of people― punks, dogs, addicts, tourists, street-drinkers, commuters, shoppers, Turkish business owners, charity-workers, beggars, buskers, families and artists. It was a place of noise and chaos, of forced-tolerance, of misunderstanding and clashes all pressed together in an array of derelict passageways, plazas, stairwells, tunnels, platforms and aboveground walkways.

Rather than constructing a model based on the positive masses of the buildings, I wanted to built and define the public space – the negative volumes – in the tunnels and between façades, following the surfaces of sidewalks and plazas, and leaving the rest as empty voids. By creating an inversion of the classic planning model I wanted to make visible the in-between, uncertain and transient spaces that delineate public life.

MM: What do you like about Kotti, and what do you like less?

LF: I like the complexity of the place – socially and historically; its liveliness and chaos; the mix of shops, cafes and housing; its atmosphere – it is a place for anyone, for everyone.

What I like less is the traffic and the traffic circle. Moreover, some of the back passageways, especially on the north-east side, behind the shops and below the first balconies. It can feel quite dangerous there and one can find oneself suddenly alone and not visible to people on the street or to the inhabitants above. Also, I don’t like the fact that the rents are going up and low-income residents are being forces out.

MM: Did your impression of Kotti change after working on it?

LF: I came to respect it more as I learned about its history, mostly from the Kreuzberg museum and archive (Bezirksamt Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg) which is based just behind the NKZ.

During the time I lived nearby (2004-2008) the shops in the NKZ kept failing – a flower shop for example couldn’t survive. Commuters wouldn’t stop at Kotti to shop and the residents couldn’t afford the goods of the shops moving in. Today shops – especially cafes and lunch places seem to be doing good business but I believe this has to do with the fact the area is gentrifying and many people now using Kotti have more money.

MM: Do you think anything should change about Kotti or the NKZ?

LF: I worry that the rents are going up. The area is becoming popular, cool, even hip and the people who have been living there for decades are being moved out. I think low-income residents must be better subsidized and/or rents better controlled to allow people to stay.

I think as well some sections of the NKZ could be redesigned to be safer, lighter, more accessible and to increase visibility – more “eyes-on-the street”.

MM: In what ways do you think Kotti/NKZ has failed? And in what ways do you consider it a success?

LF: Even within an absurd architecture that blocks light, shuts off streets and sight lines, is too high, too narrow and creates dark passageways and blind corner, there is a lot of life and energy and many different communities. I don’t think Kotti has failed. It is definitely not pretty but I believe it succeeds it being a thriving, changing and energetic place.