Future People (‘how modernism killed itself’) is an art project developed by New York based artist Yana Dimitrova, as part of her residency in Amsterdam’s Open Ateliers ZO.During her stay, Yana studied the symbols of progress, industrialization and globalization in the city’s South East area, popularly known as ‘the Bijlmer’. Among other things, the Bulgarian-born artist is interested in how residents of the single largest housing estate in the Netherlands peer into the future.

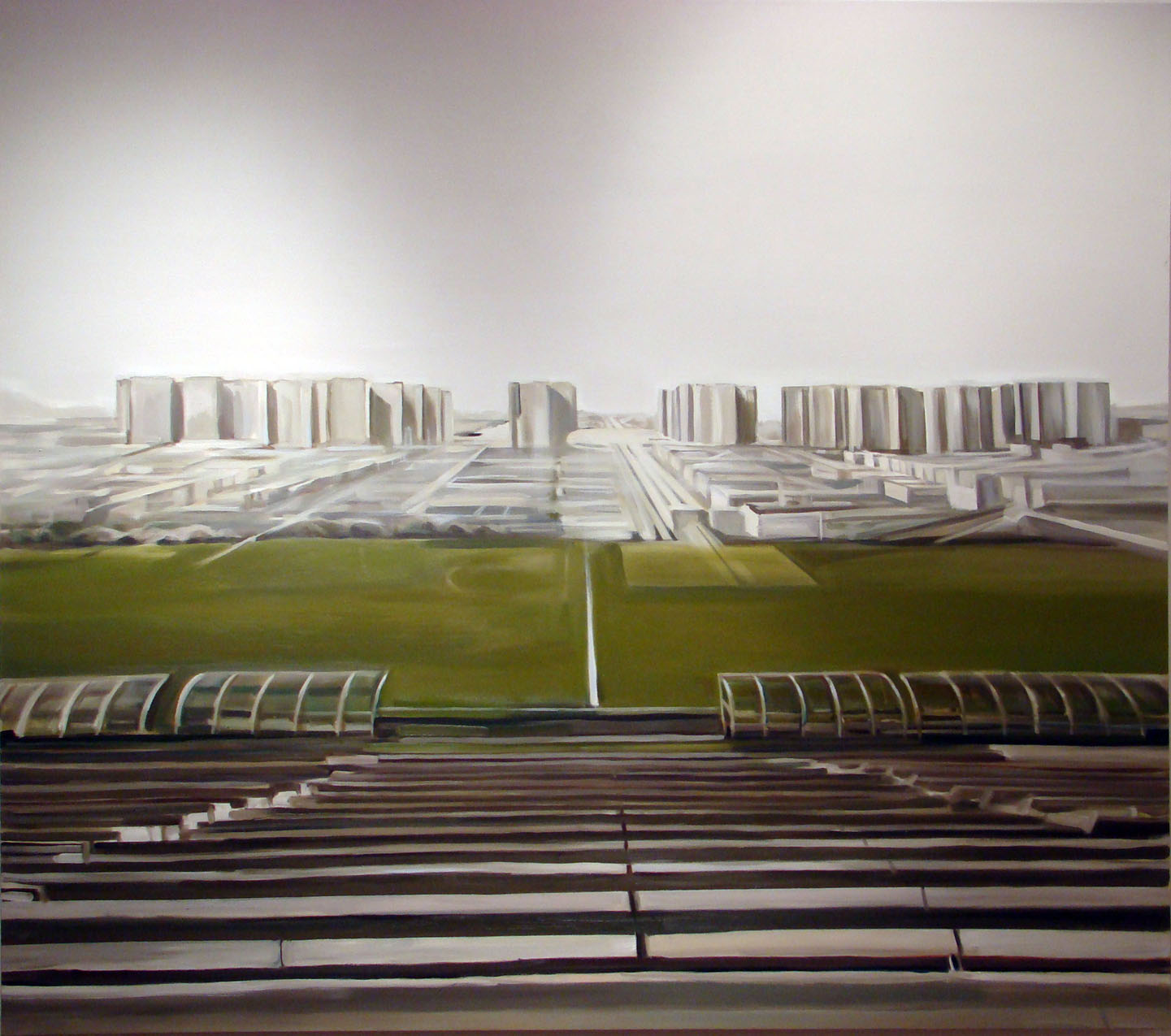

The Bijlmer’s CIAM-inspired plan, presented to the public in 1965, was based on a coherent, modernist design of repetitive and uniform superblocks. The utopian plan strongly adhered to the designs of Sheffield’s Park Hill and Toulouse’s Le Mirail developments. Although initially met with great enthusiasm, the Bijlmer soon received a bad press due to high vacancy rates and a severe lack of everyday amenities. From the mid-1970s onwards the estate became synonymous with crime and poverty. The Bijlmer soon shared the same fate as so many other post-war housing schemes in the Western world: it turned from utopia into dystopia. In the early 1990s the municipality and housing corporations initiated a large-scale regeneration scheme to enhance the Bijlmer’s urban fabric. Since then, the number of high-rises in the estate has been reduced from 95 to 45 percent of the total building stock, concrete underpasses and alley ways have been demolished and residents have been provided with more amenities.

While most of the utopian aspects of the Bijlmer’s built environment are gone nowadays, the question remains what is left of the initial ideals in the hearts and minds of the residents themselves. In her research project, Yana focuses on how the visions of the current Bijlmer residents and the future itself are opposed and function today. For her, researching the past, present and future of the area is also a personal journey. Yana: ‘As an artist in residence, I felt quite at home here. The Bijlmer is so similar to the estate I grew up in, that I actually felt mesmerized.’ She also points out some striking differences. ‘The Bijlmer really feels as if it’s from the future. If you compare this estate to similar developments in Sofia or Brooklyn, this place looks beautiful!’ Yana thinks the Bijlmer’s bad reputation has more to with the social fabric than the architectural qualities of the tower blocks: ‘In Bulgaria people with middle and high incomes still live in flats like these, whereas the poor live in individual homes on the countryside. That’s probably the main reason why modernist tower blocks are not considered to be failures in my home country.’ She does not think modernist architecture itself has failed, but rather the political systems with which it was aligned during the post war era. ‘When buildings are unquestionably constructed in the name of something, chances are they will get torn down. In that sense I think postmodern cookie cutter houses, which were built in a more individualistic laissez faire spirit, can fail just as easily.’

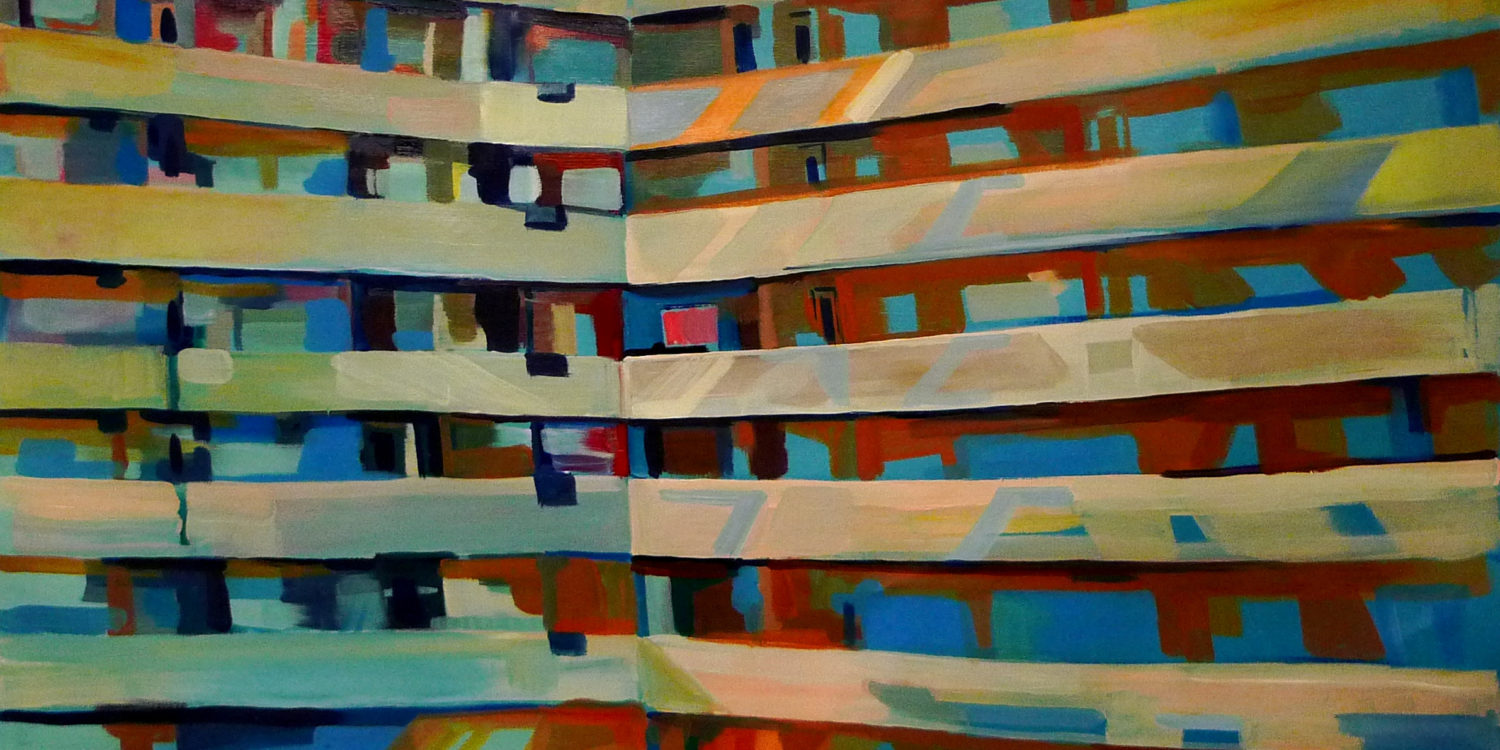

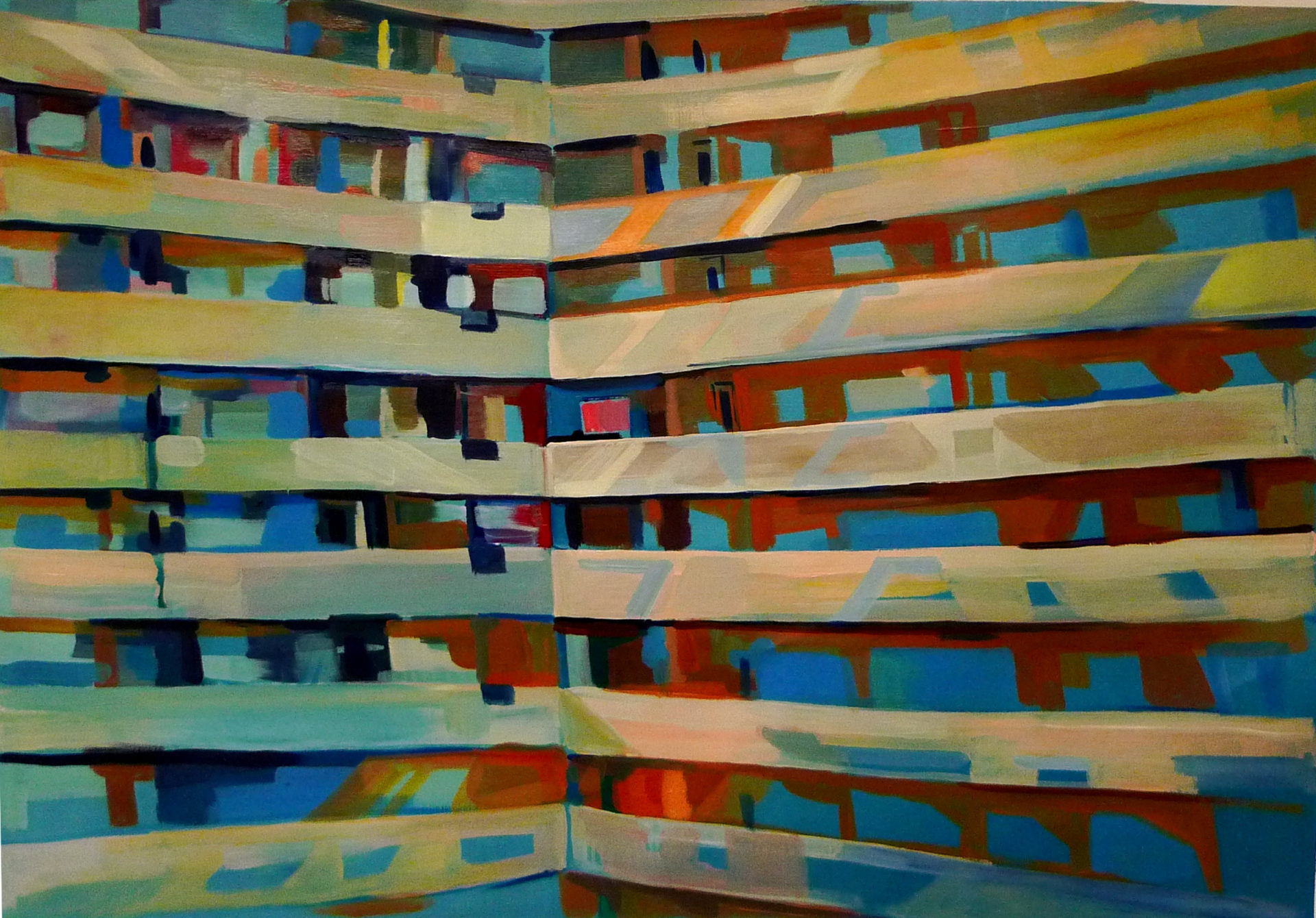

While the subtitle of her art project – ‘how modernism killed itself’ – suggests otherwise, Yana has a favorable opinion of modernist architecture and the ideals behind it. Yana: ‘I sincerely believe architecture is capable of achieving certain idealistic objectives. The communal areas of the estate I grew up in truly enhanced my friendships.’ Despite this rather positive take on modernism, her work is mainly concerned with feelings of dread and fear. The people in her paintings, often surrounded by modernist urban environments, seem to feel estranged to say the least. Yana: ‘This really crazy, utopian idea of embarking on an unknown mission and the radicalism by which architects such as Le Corbusier were in pursuit of a better future in disregard of the negative consequences, is what fascinates me the most.’ Repetition plays a big role in the artist’s work. Repetitiousness is also one of the critiques modernist architecture often receives. Yana: ‘Repetition creates voids: there is no sequence, no beginning and no end. It creates a liminal state that might estrange people who have to cope with it.’ Through the use of paintings, drawings and installations, Yana aims to construct a ‘deceptive space’, questioning concepts of desire and the proposed values of the every day. In this way her work often functions as a social critique or commentary.

With regards to her ongoing project in the Bijlmer, Yana discovered residents are not really concerned with the built environment in which they live. Yana: ‘People are having a hard time here, but they don’t blame architecture or the physical state of the buildings in which they live for it. It’s much more their financial and social situation, and adapting to everyday life in this country (the Bijlmer is known for its high proportion of residents of varied ethnic backgrounds, TV).’ According to Yana, local residents are rather ambivalent about their future: ‘They talked a lot about good morals. Religion seems to be very important; some of the residents are expecting the second coming of Christ soon. Others were talking about flying cars in a very utopian way, still some think they actually are the future because of their multi-ethnic, globalized living environment.’

At the moment, Yana is reworking the residents’ statements into several social-realist portrayals, hereby trying to depict the man or woman of the future. Eventually she might also combine the paintings she made during her stay in the Bijlmer with images from Dimitrovgrad, a modernist Bulgarian settlement dating from the late 1940s.

For more information about the project, please visit http://www.oazo-air.com/calender/event-50. Last but not least, a little song about chimneys that inspired Yana whilst working in the Bijlmer.