In April the Getty kicked off its much-hyped four-month initiative Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in Los Angeles. Long story short, seventeen different cultural institutions in and around the city are collaborating to present several shows about L.A.’s role in the development of modern architecture as we know it. The trusty exhibition subjects range from A. Quincy Jones to Ed Ruscha, all of them spreading the gospel that L.A. is an important place with important people in it, and that “architecture” is a gummy word with enough stretch and bounce to incorporate photography, art, and “other.”

More than once I’ve heard the initiative described as “finally giving Los Angeles its due.” Seeing as the topics of the shows reach as far back as the 1940s, would this mean that the city’s gone at least seven decades waiting for a tip of the hat? I can’t argue this point with the confidence of someone who’s “been there,” but it’s common knowledge that L.A. used to have a very different connotation, both within and outside its borders. Sticks and stones can make Zen gardens here, but “cultural vacuum” is a pejorative most L.A. old-timers resent from experience.

The L.A. of the last decade (and especially the last five years) seems acutely aware of a past inferiority complex — a product of external name-calling as much as internalization — and it’s vigorously trying to shake it off. Today it can seem like a city on uppers, in which a great amount of well-intentioned chest-swelling takes place. Talks and lectures at cultural institutions often escalate (or deteriorate) into deliberations about just what makes L.A. so great, strange, or terrible – but terrible in a way that still makes the city sound exciting or important. I wouldn’t call it narcissism, so much as a kind of temporary Freudian fixation. Los Angeles, a city always filled with newcomers, seems curious about itself and its “new” reputation with others. Like a method actor, L.A. is getting used to playing a different part. That “Neutras” and “Schindlers” have become prime real estate, after years on the endangered species list, is a very well-documented sign of the changing times.

Among the flood of people who come to Los Angeles, a significant amount are artists and architects, or people who hope to identify as such, looking for more space, warmer weather, privacy, a change of pace, or even the chance to weigh in on discussions about a charged city in some kind of flux. L.A. is noisy with observations and opinions. The shows that make up Modern Architecture in Los Angeles suggest that someone’s listening. Moreover, the initiative is an attempt to articulate the city’s hum and parse some of its muddied sentences: who are the people being discussed, where are the places still to be discovered, and what projects have continued relevance?

More exhibitions are scheduled to open throughout the summer, but from what I’ve seen so far, I’ve been particularly struck by Overdrive: L.A. Constructs The Future 1940-1990 at the Getty Center and A Confederacy of Heretics: The Architecture Gallery, Venice, 1979 at the Southern California Institute of Architecture [Sci-Arc]. The former lauds itself as “the first major exhibition to survey Los Angeles’s complex urban landscape and diverse architectural innovations.” The latter, which commenced the entire initiative, has a much more specific scope: it focuses on the temporary architecture gallery that ran out of Thom Mayne’s pad in 1979. The two complement one another well, and accent the important yet contrasting L.A. institutions in which they are presented.

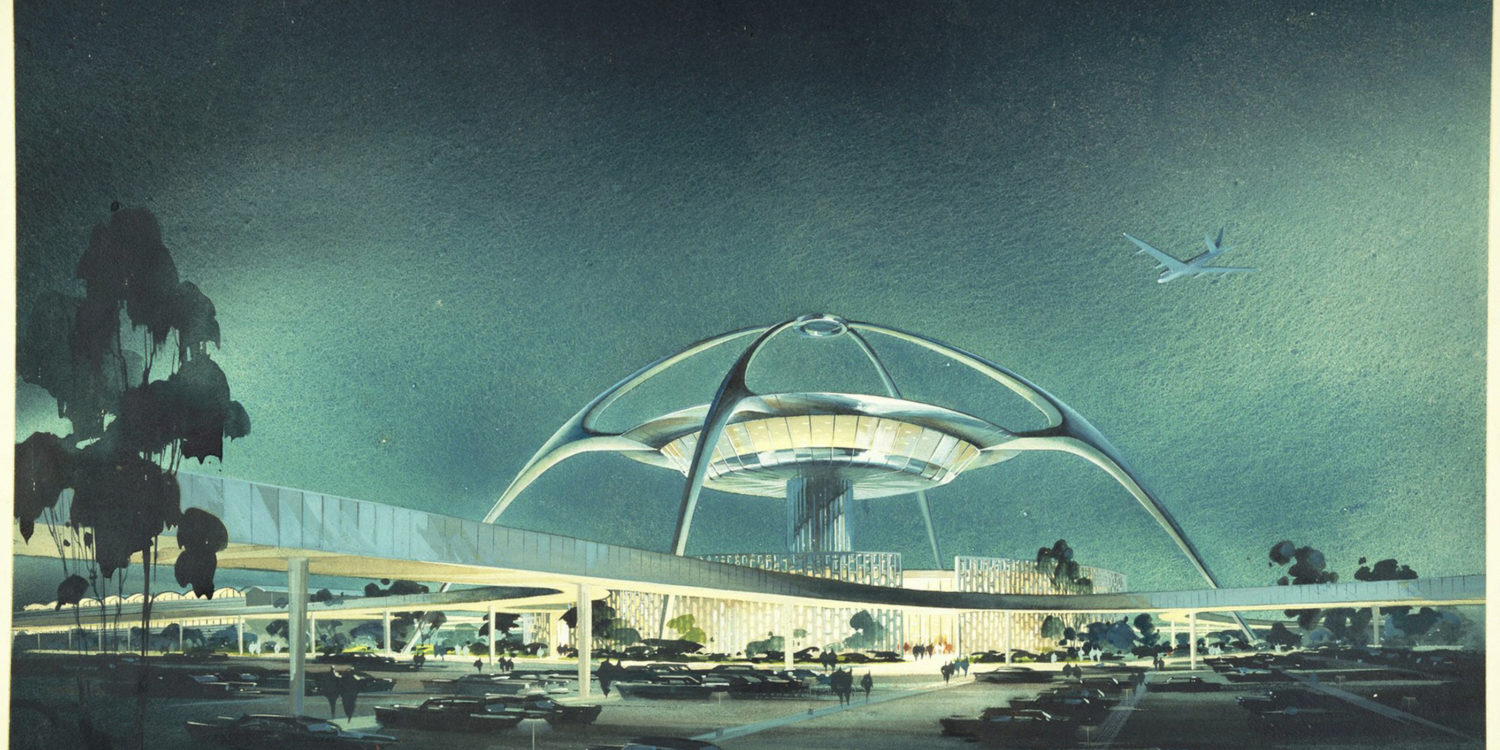

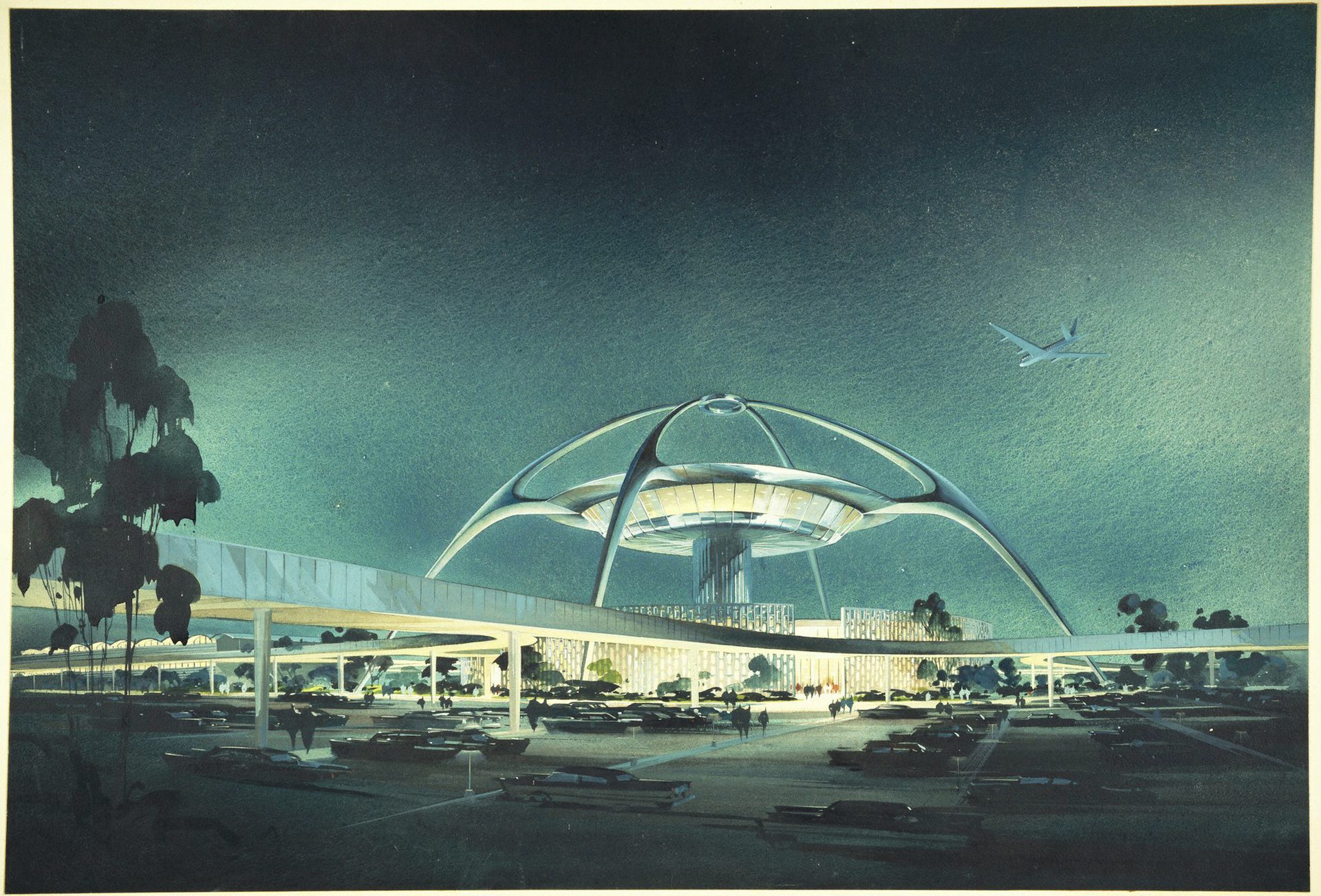

Overdrive is a strong, comprehensive look at the speed, magnitude, and repercussions of L.A.’s massive expansion and evolution. Visually, L.A. lends itself to kitschy, overly-nostalgic looks at “yesterday’s futures,” but Overdrive is conscious of this pitfall, careful to take an approach that’s not all Googie Lite. It contains serious and complex considerations of topics like urban infrastructure, airports, the 1984 Olympics, and even the architectures of faith — literal places of worship among them. That the show drops us off in the 90s allows for a more immediate dunk into present-day Los Angeles, as it is anchored by decisions made in decades immediately preceding ours. Emerging from the exhibition rooms of Overdrive’s models and plans into the real-live architecture of The Getty Center itself, overlooking the 405 Freeway, is a staggering experience. Even if this encounter can feel quite meta, the show itself is not – sparing the viewer yet another spelled-out conversation about the importance of a fluid, unformed incomprehensible now.

A Confederacy of Heretics is equally impressive in its scope, but perhaps more gestural than the composed and cerebral Overdrive. Confederacy regards the ideas, models, and manifestos of architects like Mayne, Michael Rotondi, Frank Gehry, Eric Owen Moss, and the many others who presented work at Thom Mayne’s makeshift gallery. The show has a “Behind The Music” feel, a documentary of atmosphere as much as architecture. That atmosphere, concentrated into a single show with amazing archival photos of the heretics in question, appears as “excitement in sepia tones.” The impression one gets is of a burgeoning, artistic hotbed, a salon of intellectuals. But that impression, of course, is colored by a romanticism of the past, made all the more evident by a feel-good noun like heretic (at least we’re not talking “rebels,” here). Surely this is the edited version of what happened, but the show is still a welcome example of how interesting things happen in cities suffering from complexes. To earn the distinction of being overlooked, L.A. must show exactly the aspects of itself we’ve failed to see so far, and an initiative of this kind helps give substance to a city’s swagger. Los Angeles architecture may just be getting its due now, but even recognition needs a strong, earthquake-safe foundation to stand on.

This article was originally published over at our friends of Uncube magazine.