”Recently we have witnessed the mounting of very large development projects in European and American cities. There is a striking physical similarity among the schemes and also a convergence embodied in private-sector involvement and market orientation.” (Fainstein, 2009: 768)

Although joint collaborations in the form of public-private partnerships are by no means new, they gain importance in all levels of present large-scale urban developments in Europe. The increasing number of alliances between state and private capital mirrors a market-led approach to city planning and reminds us of the relevance of a debate around this matter.

The term ‘public-private partnership’ is to be understood as a negotiated business deal in which trade-offs are made, and risks, benefits and profits are shared (Longa, 2011). The cooperative partnership applied to urban models will have a big impact on the way we plan cities and the question is how to keep the balance between “control and laissez-faire” (Christiaanse, 2009: 22).

Zoom one: Europe

According to Christiaanse (2009) European cities seem to have developed a new generation of tools for urban development. This reflects a Europe where “cities are copying each other’s formulas and specific characteristics” (Mimica: in Christiaanse, 2009: 53). This dedication to a common toolbox in urban planning makes it possible to have a debate around current trends in urban management across Europe. The point of departure for this discussion is set in Ørestad, Copenhagen – however the same study could equally well have been carried out in a dozen of other mid-sized cities in Europe.

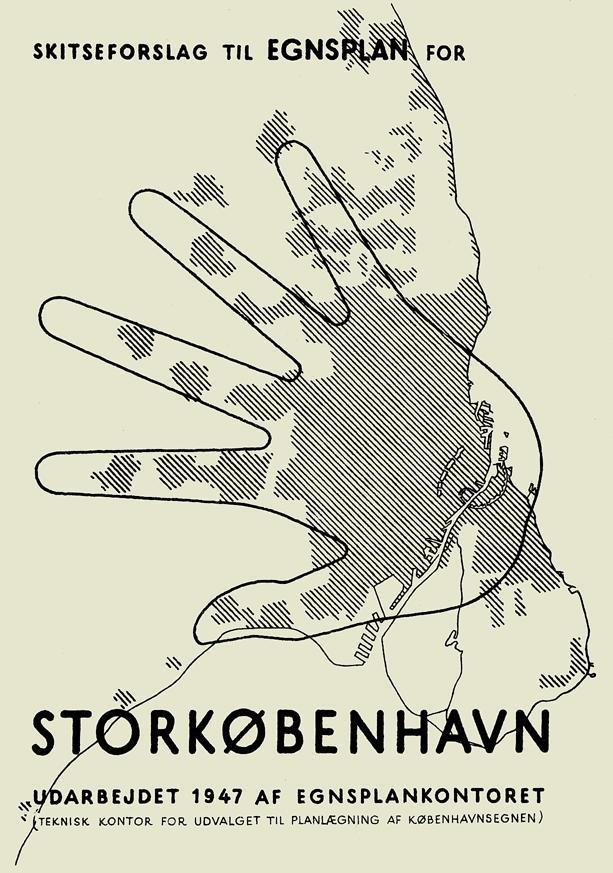

The European planning trend illustrates an increased use of the strategic master plan in which public-private partnerships play a significant role and it also illustrates a shift away from traditional planning tools, as we know it from the zoning plan (Christiaanse, 2009). This is also present in Copenhagen and the following will depict the shift from a period of stable development, exemplified by the ‘Finger Plan’ to one of market-oriented thinking.

Zoom two: Copenhagen

Worked out in 1947 the ‘Finger Plan’ became a representation of modern state-led planning in Copenhagen. Especially after the Second World War the plan successfully helped control suburbanization in corridors around infrastructural veins that were connected to central Copenhagen by a rail system. In between the linear suburban developments, green zones prospered (Hartoft-Nielsen, 2007).

It was the ‘regional plan committee’ under the state that formed the layout of the Finger Plan and their initial inspiration for the plan was found in Abercrombie’s ‘Greater London Plan 1944’ (Jensen, 1990). From 1947 approximately 240.000 new housing units were constructed. Planning, rationalization and industrialization of the housing construction following Le Corbusier and CIAM Modernist principles were prevailing and reflected a new, strong relation between the architect and its client – the state.

As the Finger Plan took shape, so did the city. The most privileged population saw itself moving out into the suburbs leaving behind inner-city neighbourhoods in poor conditions. Two major issues influenced the decision making of the Copenhagen authorities at this point. Firstly, the suburbanized control in a northwest direction towards other municipalities resulted in an erosion of the tax base of the city of Copenhagen (Majoor, 2008). Secondly, an international debate around the issue of globalization and city competition arose and pushed Copenhagen into new metropolitan strategies and partnerships to attract affluent inhabitants.

Similar to a number of other cities, a renewed focus was put on the industrial areas along the harbour front. This provided opportunities for new approaches in the property market and for new collaborations between private investors and the public sector. The ambitions were high and the atmosphere became almost euphoric: the development of the North Harbor, the Inner Harbor (providing the Copenhageners with a new Theatre House by Lundgaard/Tranberg, a new Opera House by Henning Larsen and a new Arts Academy at Holmen), the South Harbor (with the Harbor Bath of PLOT and MVRDV’s silo-dwellings at Islands Brygge; and Sluseholmen by Sjoerd Soeters) and with the development of Ørestad (with a.o. the Concert Hall of Jean Nouvel). As you can already tell by the number of acclaimed masterpieces it was nearly as constructing a new Copenhagen within the existing one. It can be argued that the many new developments along the harbour front became a competitive factor and very influential on the outcome of the Ørestad project.

Another important focus was put on the new cross-border region between Copenhagen and Malmö and the connection with the Kastrup International Airport, placing the region as a new focal point in the Nordic domain. And since the East opened with the fall of the Iron Curtain and Sweden and Finland were going to be part of the EU in the near future, Copenhagen was made to be a new focal point in Scandinavia.

In many ways the development of Ørestad epitomized a break with the original Finger Plan. First of all the orientation of development altered – pointing eastwards towards Malmö away from the fingers, secondly the planning of Ørestad reflected the changed role of the state – now working in closer relation to private investors.

“Following a long period of stable development of the welfare city, in which the relationships between different stakeholders were fairly constant and the planning system was very influential, the impact of globalization and market-oriented thinking tore what seemed to be a well-established order into pieces” (Kvorning in: Christiaanse, 2009: 175)

Zoom three: Ørestad

Walking through the streets of Ørestad one remembers a critique often heard: the fragmented urban fabric is vast and compiled by public spaces of poor quality. It can be hypothesized that an unequal balance within the public-private alliance caused a disjointed urban tissue in Ørestad City. To explain this assumption we will point at two critically discussed and characteristic objects in the plan: the metro and the shopping mall.

The metro

The formulation of the policies behind the embryonic, driverless metro in Ørestad had two goals. The one goal was to realize a new public transport system, which would be directed by the Ørestad Development Corporation (owned by the city of Copenhagen and the Ministry of Finance) to service not only Ørestad but also Malmö and Copenhagen – the other goal was to sell out building sites along this new metro line “especially targeting high-paying multinational private firms” (Majoor, 2008: 138). The profits from the sales of these sites would then consequently finance the metro.

This alliance made around the development of the metro was a way to share risk and profit, but at the same time it provoked a dependency between the two actors. Whether this state of reliance was to be considered beneficial or not – whether it was favourable for the state to rely profoundly on private investors – is a cornerstone in the debate around public-private collaborations.

The same alliance can be associated with what Richard Sennett disapprovingly refers to as ‘the closed system’ – ruled by the balance of income and expenses:

“The closed system ruled by equilibrium derives from a pre-Keynesian idea of how markets work. It supposes something like a bottom line in which income and expenses balance […] familiar to urban planners in the ways infrastructure resources for transport get allocated.” (Sennett, 2006: 2)

In the planning of the metro, a system similar to that of ‘the closed system’ became the fundament for the development. Without the metro there would be no Ørestad – and the two, as we shall see, became heavily dependent on each other. By stressing the importance of the metro and the new bridge to Malmø, the Ørestad Development Corporation furthermore tried to evoke an image of connectivity, aiming at a cosmopolitan user group in a global setting.

Despite big anticipations, the Ørestad Development Corporation was faced with substantial challenges, as the development of the metro didn’t go as planned. This turned out to be the most crucial issue in the development of the Ørestad project. Massive cost overruns in the metro construction, disappointing ticket sales, larger debts than foreseen, a severe lack of interest in the building plots around the metro line – subsequently forced the Ørestad Corporation to serve according to harsh market terms opposite to the initial urban planning ideas and allowed the private Norwegian developer Steen & Strøm to construct a huge inward-facing shopping mall at the most prominent location in Ørestad (Majoor, 2008). We argue that the shopping mall is the most visible result of the state’s turn towards market-oriented planning.

The shopping mall

The shopping mall became a safeguard project for the state. Opened on 9th of March 2004 the huge box-type centre, named Fields, with vast display windows and only one huge, main entrance dropped down at one of the most alluring parcels in the centre of Ørestad. The state had found a project to generate revenues to pay back the large debts from the metro investments. Enthusiastically the Ørestad Development Corporation congregated and advertised the initiative:

“Fields is the largest shopping and leisure centre in Scandinavia [178.999 m2] Besides a wide choice of shops, the centre also boasts many different restaurants and leisure activities, e.g. a children’s fun centre, a 12 hole indoor golf course, hairdressers and a fitness centre. In the future there will also be offices, a hotel and a cinema” (Christensen, 2007: 42)

Establishing Fields on the one hand bailed out the Ørestad Development Corporation of its at that time severe debt operating closely on the premises of the private sector, on the other hand outdistanced the connection to citizens and their local needs. This could be seen in the light of three issues:

1. Launching Fields had been decided by the Ørestad Development Corporation, thus supported by the state, against Danish planning guidelines, which prevented large out-of-town shopping centre construction to protect local trade (Majoor, 2008).

2. The whole Ørestad project was initially controversial: the area was vacant because it was a protected natural park. With the Fields initiative the controversy became further intensified by assertions from environmentalists groups who referred to the expected increase in car traffic (Majoor, 2008). The Ørestad Development Corporation ignored this citizen-represented group.

3. With regard to street liveliness the central area of Ørestad, with the construction of Fields, ultimately lost its opportunity for real urban quality. As raised by Kvorning: “The large shopping mall was allowed to turn in an inward-facing direction, without the slightest attempt to create life in the surrounding streets” (Kvorning in Christiaanse, 2009: 187).

Research of ‘Kay Fiskers Square’ (the new central square in Ørestad) by Jan Gehl substantiates this assertion. In spite of 7000 pedestrians daily the square remains rather empty all day. The average number of people present on the square is 5.5, which reflects the transitional rush from the metro to Fields. As comparison is given the ‘Aker Brygge Square’ in Oslo which is used by 5000 pedestrians daily but has an average number of 212 people present on the square (Gehl, 2007).

As an object, the shopping mall in Ørestad remains one of the most present results of the state’s panicked turn towards private-sector involvement and market orientation. Fields generates a big turnover thus belonging to the group of big-profit forms that Fainstein has described as “luxury residences and hotels, large-footprint office towers and shopping malls […] lacking the layering of old and new, small and big, that gives central cities their ambiance and opportunities.” (Fainstein, 2009: 783)

The outcome of especially the Ørestad City, mentioned above, is not a fruitful situation for neither private nor public developers. It is obvious that within a public-private partnership both sectors want minimum risk and maximum profit. Despite Ørestad Development Corporation’s initial ambitions for urbanity the risk of joining the project has proved huge: very little profit is made at the moment as most apartments and office projects are impossible to rent out or sell.

Looking abroad

In France an interesting alternative variant of the public-private model exists: Société d’Economie Mixte (SEM). Here developers obtain only up till 10% of the profit. Profit beyond that will be shared, meaning that half of it goes directly back to the state. In this way SEM is a variant of the public-private partnership where the risk levels and the profit levels are clearly clarified – this results in a better balance between public and private interests and limits the number of private investors only seeking short-term high revenues. For the developers on the other hand, the big advantage is that, because the state is profoundly involved, they are sure of high investments in infrastructure and (preferably) in the quality of the built environment.

In Amsterdam the public-private partnership model proved to be a highly desirable one when used for the redevelopment of the Eastern Harbour District. A strong publicly framed development corporation (led by the municipality – Dienst Ruimtelijke Ordening – and with Soeters, West 8 and Coenen as executing design responsible for the different areas) safeguarded the project from the beginning and limited the risk for private investors joining. The development of The Eastern Harbour District proves that cooperation between the public and private sectors can offer high quality results with a good public outcome. Its success may also be seen in the perspective of its scale, its primary aim at housing development and its close connection to the city center. The profitable outcome of the Eastern Harbour District, however, remains a counterpoint to the problematic development of the Zuidas in the same city. The critiques of the Amsterdam Zuidas show similarities to those of Ørestad: being a very large-scale development, with a strong business orientation and a particular focus on infrastructural requirements – factors that involve large public investments and factors that raise the urge for high profits. As a consequence, negative pressure is put on the urban quality.

The lost ones – urban use values and democratic space

Throughout this essay we highlighted the danger of a low quality urban space in relation to the state’s turn towards market-oriented planning. The Ørestad project started with an overwhelming array of optimism and ambitions, glossy project folders and flashy websites presented an image of the development as becoming the opposite of a dull and monotonous place, full of vibrant urbanity. But if we look at the built environment of Ørestad today we see that large parts of the urban areas are disjointed with “architecturally indifferent and totally oblivious objects” (Kvorning: in Christiaanse: 187). Numerous previous studies already revealed the difficulties in transforming the often imaginative intentions for new urbanity into a built reality. The public spaces in Ørestad lack the friction of user groups and ownership, the overlap of scales, to be successful.

The aim of Ørestad to create a vibrant urban life and at the same time primarily service an affluent cosmopolitan elite runs the danger of ending up with public spaces that are too homogeneous. Furthermore, the privately developed individual architectural masterpieces have a tendency to stop designing at their front door, resulting in a cityscape as an ‘island of blocks’ with a lack of coherence and resistance in the public realm.

“Throughout Ørestad’s development there were huge difficulties connecting the project to the social, civic and cultural domain. In the initial phase, the project was heavily criticized for its exceptional status, and this made it more difficult for non-governmental groups and citizens to participate and influence its development.” (Majoor 2008: 129)

The second aspect in this discussion is concerned about the role of the government vis-à-vis private investors and its negligence towards ‘the third player’ – the citizens and NGO’s.

What we have seen working well in e.g. Spitalfields in London, where groups like Spitalfields Small Business Association challenged the planning of the city from below, this kind of dynamics hardly had influence in any part of the Ørestad project. Because of the scale of the plan and driven by the need for high profits, the Ørestad project developed in a top-down and non-participatory way. This while Denmark traditionally has a strongly present civil society and participatory local government system. Furthermore, because of the environmental issues at hand in the area, there was enough reason for public discussion and protest. In the case of Ørestad however, the government gave an ‘exceptional status’ to the development because of its (inter)national importance, ruling out local influences. This may have been productive on a management level, but had a very negative effect on the judgement of the project in the public opinion.

“City marketing may be dangerous if it leads to crucial aspects for future development such as social considerations being left behind” (Schüller in: Christiaanse, 2009: 70)

When politicians hand over too much power to private parties they lose the opportunity to take local interests into consideration. This undermines the local democratic process and can be a negative effect of the public-private partnership. As we have seen, the public-private partnership can be successful, yet the Ørestad project shows that an important factor in guaranteeing urban quality is to keep public influence throughout the process.

“The contemporary mega-projects […] indicate that public-private partnerships can be a vehicle for the provision of public benefits, including job commitments, cultural facilities and affordable housing. They also show, however, that such projects are risky for both public and private participants, must primarily be oriented towards profitability, and typically produce a landscape dominated by bulky buildings that do not encourage urbanity, despite the claims of the project’s developers.” (Fainstein, 2009: 783)

A multifaceted profession

It is exactly this difficult balance put forward by Fainstein that we discussed. This essay doesn’t try to blame the public-private model for certain urban failures, but rather tries to make clear what factors are determining a positive or negative outcome. Looking at the role that, for instance, architectural firm BIG played in the Ørestad development, this leaves us with the question how we should position ourselves as architects and urban planners in this contemporary power structure. Should we work in close affiliation with private investors who give us room to express ourselves – or will this limit our social role? Will the state only allow us to build the mediocre – or do we need public influence to add meaningful and long-lasting buildings and spaces to the city? In the precarious balance of public-private partnerships the answer of our discipline to those questions will be crucial in guaranteeing the quality of our future environments.