At present, the urban character of post-communist cities is being shaped by ongoing societal and spatial processes, and their societies are increasingly polarizing. By regarding public space as one of the exponents of a just city it is critical to see it as an articulation of issues such as social and spatial inequality which are common within a post-communist discourse.

As such, this article tries to shed light into the present condition of post-communist public space. By examining how post-communist cities presently recreate their public space it is argued that this typology is increasingly becoming privatized, a phenomena which fuels the already burgeoning fire of their segregated societal base.

Bucharest, together with one of its most popular elements of post-communist spatial production (i.e. the office building) are used as a case study. The reasoning behind this is three-fold. Firstly, Bucharest presents some curious evidence of multiple, different forms of public space throughout the various political regimes that took residence here.

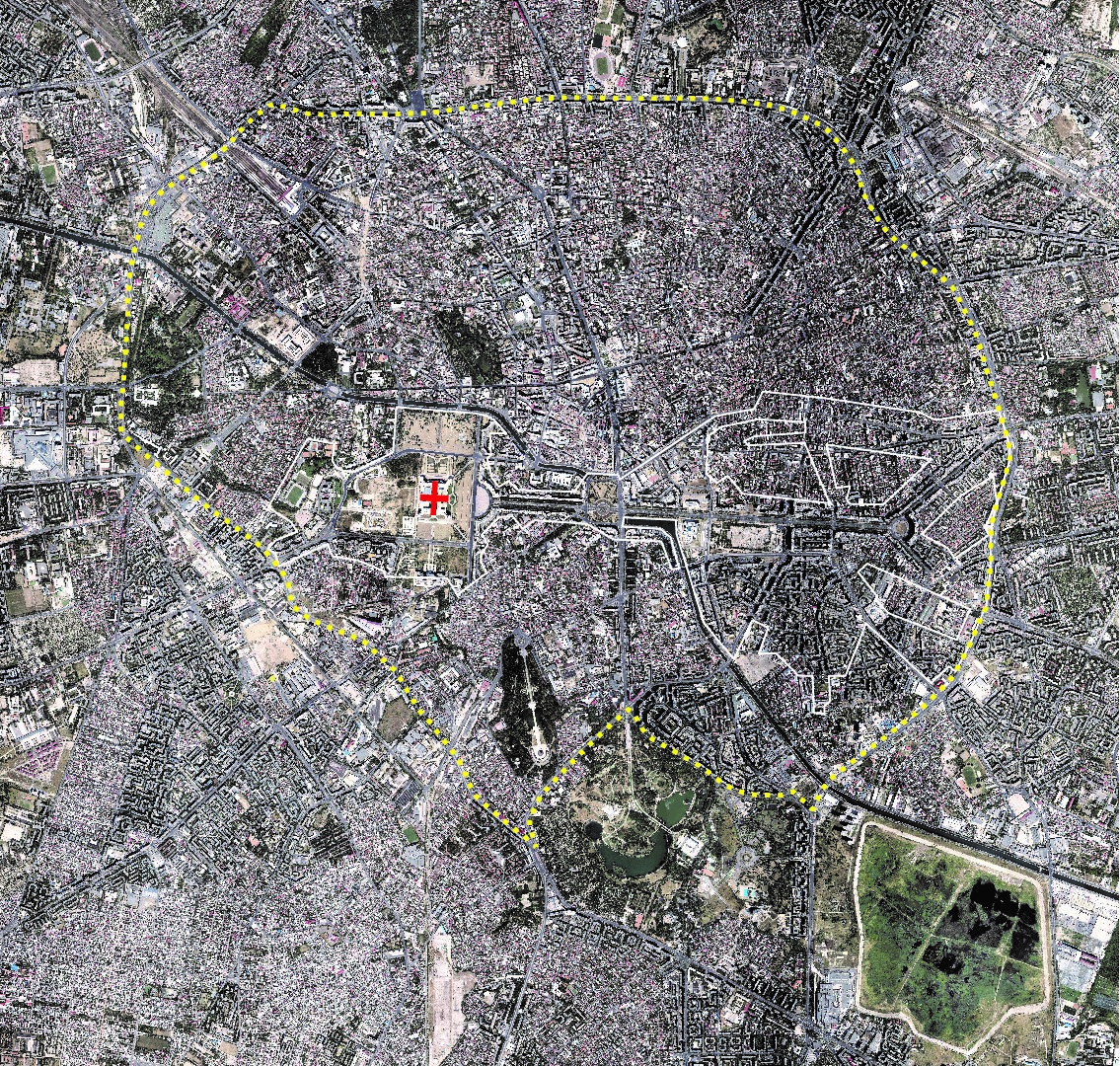

Secondly, this is a perfect example where exclusive income-based uneven spatial development has exacerbated the already polarized nature of its society by splitting the city east-to-west into two poles of different spatial and social characteristics. The north of Bucharest gathers the income-level elite of the city while at the same time offering the bulk of amenities and economic activity. Conversely, the south is lacking behind with regards to its urban development, and takes in much of the poor and disenfranchised share of the city’s population

Thirdly, apart from privately driven development projects, initiatives that deal with public space in the city have been scarce to almost non-existent. Moreover, the greater majority of private projects fail to contribute anything to the city’s patrimony of public space.

Before Communism

First and foremost, it is important to point out that public space in Bucharest has had a unique evolution. One of the initial manifestations of public space in the city dating from the early 18thcentury was a natural enlargement of the street or maidan in Romanian terminology. These purely vernacular places replaced the conventional urban square as supporters for public life. It is important to note that the aforementioned urban square is entirely absent from the city’s urban structure.

Subsequently, the late 19th century introduced the French-inspired Boulevard as a tool for adding monumentality and urban coherence as Bucharest became the seat for the ruling monarchy. The boulevards together with the proliferation of the public garden were the premiere places for urban life in the city.

To put it short, the bulk of public space in Bucharest at the turn of the 20th century was represented by the enlarged street lattice of maidans, the late 19th century boulevard and the public garden or parks.

Communist Comprehensive Public-Space

During Communism this condition more or less remained the same. However, Communism had an influential role in bringing a different type of public space, one that clashed with the inherent identity and spatial logic of the city. One project stands out as being most representative.

Through the development of The New Civic Center and The People’s Palace in the early 1980’s a huge part of old city was replaced by what essentially is deemed big architecture. Where previously used to exist a homogenous, organic fabric of public places intimately servicing local communities was overtaken by the tabula-rasa urban frenzy of Communist comprehensive development which introduced a myriad of urban voids as event-places for the representation of power, immense collective housing walls and monumental boulevards which seemed to have no function for city-wide urban mobility. Besides their inherent monumentality, their only apparent reason was to dutifully set the scene for one of the oddities of contemporary architecture, the People’s Palace

As a sort of “coup de grace” in this grand urban gesture, the People’s Palace, ranking 2ndbehind the Pentagon as the largest building on the planet oversees the whole of the new urban development.

This behemoth of neo-classical type inspired architecture but with a reinforced concrete skeleton and fabricated stone facades of questionable ornamental quality seemed to represent “bigness” before the term was invented. However, while “big” buildings reinvent their context the Palace serves no other purpose but to emphasise political power and drive urban blight. It is almost ironic that the whole urban project and its emblem, the Palace, were never finished. As a reminder, a huge gape of free urban land flanks the Western side of the building.

Essentially, The New Civic Center destroyed a quarter of old city urban tissue and its local public space, uprooted communities and walled off this part of the city with big residential buildings for the ruling communist party elite. At the same time, the traditional maidan was replaced with the urban void as an alternative to public space. At present, these public spaces of the New Civic Center function as occasional event-spaces that provide no function for daily urban life.

Curiously enough, the New Civic Center is, to a certain extent, representative of the subsequent approach to urban space by projects in the post-communist era, as present projects excruciatingly fail to deliver anything worthwhile to the mass of public space in Bucharest.

Post-Communist Public Decay

As a capital of a former Communist state, Bucharest can hardly evade the effects brought on by past ideology. However, its present condition is as much a result of the last years of free-market development as it is of its former authoritarian one.

With the fall of Communism the process of urban development changed from an entirely state-controlled affair to one completely driven by the free-market. Financed mainly through foreign capital, urban development in Bucharest was at the discretion of private initiative. With no immediate opportunities for profit, the public dimension was ignored by most private projects. The reasons they succeeded is precisely through how the city manages its development of urban real estate.

In Bucharest, the document that guides development is the General Urban Plan. Functioning essentially as a comprehensive planning scheme that harks back to former Communist Masterplans, the Plan manages development by assigning land use zoning schemes, massing and density laws to urban land.

However, endless private development derogation through real estate speculation has rendered the Plan irrelevant and outdated. Moreover, before the Plan was implemented in the early 2000’s, projects in the city were almost exclusively improvised from an urban design standpoint and purely opportunistic. Profit and quantity superseded quality of urban life.

As such, three main processes characterize the spatial transformation of practically every post-communist city and with it of Bucharest:

(1) The dilapidation of its industrial real estate: the formation of industrial wastelands as a result of the shift in economy modes;

(2) The proliferation of the private spaces of production and consumption: the office building and big-box retail or the mall;

(3) The rise of suburbia and residential enclaves: the gated-community.

A special case of retail development is represented by the proliferation of small-scale retail outlets into residential neighborhoods. Generally occupying the ground floor of existing buildings these units were beneficial in creating a sense of community among local citizens. Therefore, although virtually adding nothing to the physicality of local public space, these outlets nevertheless enforced the publicness of neighborhood life.

All in all, the office building and big-box retail have enjoyed the most success as new development in the city, precisely because the projects have the greatest capacity for turning a profit.

While the big-box retail was responsible for a lot of urban damage, its general location on the urban fringe does not render it a referential example here. It is precisely how office projects embed themselves into inner city urban territory that make them adequate case-studies.

Below some examples are given of office buildings and how these projects interact with the public space in the city. These are but only a few examples of office buildings in Bucharest, however most projects show a similar design attitude. The intent is to portray some positive and negative examples.

America House – the contemporary maidan

One of the first office buildings of “western influences” to get built in Bucharest post 1990 is also one of the few good examples of native office buildings that positively engage with their surroundings. Notwithstanding the aesthetics of the façade, it is how the building touches the ground that is of critical importance.

The recessed ground floor provides an ample width to the street profile. Functioning as a sort of 20th century modern maidan it lines the street with public program reinforcing local urban life. The shops and cafés housed inside interface with the street space through a transparent curtain wall façade. Thus, life is visible on the inside but also on the outside. During office hours, employees flock underneath the portico for the daily nicotine and caffeine fix while quickly glancing at passers-by. As a sort of positive casualty of design, the cars parked by the side of the road shield the pedestrian sidewalk from heavy traffic.

Calea Calarasi Office Building

Sadly, besides displaying an overall poor quality of architectural design, this building also shows a glimpse into the train of thought prevalent throughout the local architecture profession. More often than not, local architects reduce their projects to surreal façade embellishments that hide benign and bland interior spaces with little or no relationship to outside space. Moreover, interior space, just as the façade is treated as a cacophony of finishes and tacky lighting systems.

It is almost startling how a wall of air conditioners dresses the main façade of the building. It is as if the architect was trying to completely interiorize the rentable working spaces that should otherwise be of utmost concern for design, especially when imagining an office building, where employees spend the greater part of their weekly time. Testament to this, the adjoining pixel pattern on the façade is merely a justification for the designer’s fees.

Approaching the building on the main street one cannot help but remain startled by the complete lack of any signage of entry points. Funnily enough, the entrance to the underground parking space receives more attention for design than the actual entrance of the building. The general urban laws for Bucharest usually forbid massive buildings from dwarfing neighboring structures. This is done primarily because of technical reasons, such as lighting or ventilation and also in an attempt to preserve the physical coherence of plinths at street level.

To bypass this architect has resorted to the principle of the architectural setback, a common manipulation of form worldwide (e.g. the Manhattan skyscraper). However, while the setback generally creates multiple design opportunities of a higher order, here it merely frames the banal parking entrance and, celebrates the upward shaft of façade air conditioners.

Sadly, the façade that also displays the entrance showed no physical possibility for any more setbacks. Therefore, as a solution the urban rules were decisively ignored as the neighboring house is bombarded by the fire escape stairs that scream Gotham more than Bucharest.

In the end, two dreadful examples of how this building interfaces with the street public space are pointed out.

Firstly, the entrance side of the building invades what already is quite a cramped street profile, with an apparently useless extrusion, of 50 or so centimeters from the ground, a complete and utter disregard of any urban laws.

And secondly, the entrance space of the building is completely severed from its relationship with the street, physically and visually by a set of the most disturbing stairs imaginable for any office building. In a sort of tragic twist of events, the wheelchair ramp, adorning the stairs to the right, undersized and badly placed, remains as a reminder for the downright mediocrity of architecture that this building brings upon the city.

At present the building seems to be unoccupied. Notwithstanding the implications of a current real estate crisis all around perhaps here vacancy is also strengthened by the overall poor quality of design.

Final Remarks

It is without a doubt that public space is critical for urbanities worldwide. Fully developed cities and mature governance systems tend to have strong policy tools that protect and guide the development of new public space.

Still going through considerable changes regarding their urban space and socio-economic structure, post-communist urbanities lack the maturity and knowhow that are needed to foster their public spaces. Although part of the EU, Romania and its capital Bucharest, are continuously experiencing these changes simultaneously. While having ample opportunities for urban development regarding both the market and free urban land, projects in the city are almost exclusively focused on profitability while shunning away from contributing to the public good in terms of space.

Office development, as one of the city’s most popular items of spatial production has become quite an endless source for debate amongst the design profession and academia. However, perhaps, it is not the typology that fails the city, but the overall approach and result.

One cannot help but point out that office buildings, as almost any profit-driven projects are benefic in this specific context as they generate most needed economic activity (i.e. jobs). Nonetheless, they are also damaging.

While leaving out issues such as spatial mismatch and transport inequality, office buildings at the urban periphery generally tend to have a more dormant role in the city regarding space. Nevertheless, inner-city offices are generally irreverent towards urban life.

Sadly, in a city that has not built any public buildings in the last 20 years apart but a few (e.g. the recently completed National Library), the widespread presence of office buildings could potentially contribute much to public life. Perhaps key governmental actors and civil society need to play a more active role in addressing this issue.