Soon after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia and its capital started their new ‘revolutionary’ development under market conditions. Swiftly, bitty private interests in real estate became institutionalized and started to change the social structure and architectural appearance of the city. The formerly dilapidated quarters near Ostozhenka Street were the first to be affected and experienced a rapidly increasing demand for high-class housing. What lurks behind the gentrification-like veil of the developments appears to be a direct result of Russia’s current rampant capitalism.

A mixture of a socialist past and a capitalist present gave birth to a number of unique urban processes. While these processes recall similar phenomena previously evident in European cities, they appear essentially different when examined.. Among them is the Moscow version of gentrification, bypassing the negative and positive traits of the generally gradual process of regeneration. Early Moscow gentrification incorporated all the worst aspects of such a process and took them to an extreme degree at an incredible pace, leaving no space for reflection on the positive or negative aspects of this urban process. But what exactly happened to post-socialist Moscow? How did this kind of gentrification change the city?

Among the first victims of early Moscow gentrification were the quarters around Ostozhenka Street, just 800 meters south-west of the Kremlin. This area was not only among the most centrally located inhabited parts of the city, it was also among those having the highest percentage of communal flats (70% – greatly above the Moscow average). Communal flats have been an essential part of socialist-era housing: created as a temporary response to massive urbanization they still exist and fill a significant part of the housing structure in Russian cities. It’s worth mentioning that approximately 40% of the housing stock in the area wasn’t meeting housing quality standards. In this way Ostzhenka indeed fitted one of the gentrification criteria – it was an urban area suffering from disinvestment.

“Moscow is not really a city, it’s more of an agglomeration of badly structured spaces. In Moscow, it was more important to create emptiness than purpose. All these stories of gentrification of Moscow were made up by people who could read books well enough and learn from the obscurely explained theories of gentrification processes.” – Alexander Gavrilov, literature critic

The gentrification process started with communal flats becoming subject to the state-secured housing quality improvement program , obliging its tenants to get their personal flats sooner or later. ‘Later’ is a dominant strategy in Russia and it was used by the nouveau riche to buy up the shares in communal flats to become sole owners of the property. Often the shares were traded for small but private flats in new houses in the city’s outskirts, displacing the population of the area. Having acquired control over all the shares of the communal apartment, a new owner usually found himself in what was a luxurious pre-revolutionary bourgeois flat that had gone through 80 years of neglect and decay, definitely not the best high-class housing option, but at least centrally located.

The second phase of Ostozhenka’s gentrification included real estate development and was connected to various other developments in Moscow. Russia’s 1998 financial crisis for example increased business interest in real estate investments, which was supported by city authorities. They enabled expensive regeneration and restoration processes in the district by just closing their eyes to it. The most popular scenario followed was similar to the 1950’s Brussels-style façadism. Apart from the façade, the rest of the architectural monuments were completely demolished, replacing them with new fancy apartment houses that barely met any regulations or construction norms. More and more developers became interested in the process of Ostozhenka’s ‘revival’. In around 2006 – that is, in just 8 years – more than 60% of pre-revolutionary preserved housing had been demolished, only to make way for bigger and more expensive houses. Real estate prices rocketed – topping at an insane $35000 per square meter in some cases. This moment signals the Ostrozhenka’s complete divergence from the stereotypical gentrification process.

“We should admit: Moscow’s real estate is expensive. If you want to earn money then you can. If not – move to your relatives in the outskirts and communte into Moscow three hours every day.” – Leonid Kazinets, CEO Barkli Development Group (one of the major ‘Golden Mile’ developers) and Member of the Presidential Council for Housing Policy and Affordability.

Ostozhenka’s transformation from a tranquil and rundown district into a new rich Muscovites’ nest wasn’t only rapid, it was also relentless. By demonstratively ignoring the problem, the most devastating role in the district’s gentrification was played by Moscow’s municipal government. All the aspects of city development that should have been under its control were set loose. Neither in Ostozhenka nor in other districts were functional zoning, construction volumes, service infrastructure, population density, and heritage preservation properly regulated. Unfortunately for Moscow, its top-league (so called World or Alpha Cities) position also meant that the city was among those most affected by economic transitions and new developments. In order to obtain a desirable Western and capitalist image, Moscow started to get rid of signs of socialist disinvestment in the most frenzied manner. But in contrast to the Western world the controlling levers between society and politicians had yet to be established, which gave carte blanche to the developers and the top administrative circles to deploy solutions designed with the sole purpose of extracting maximum profit.

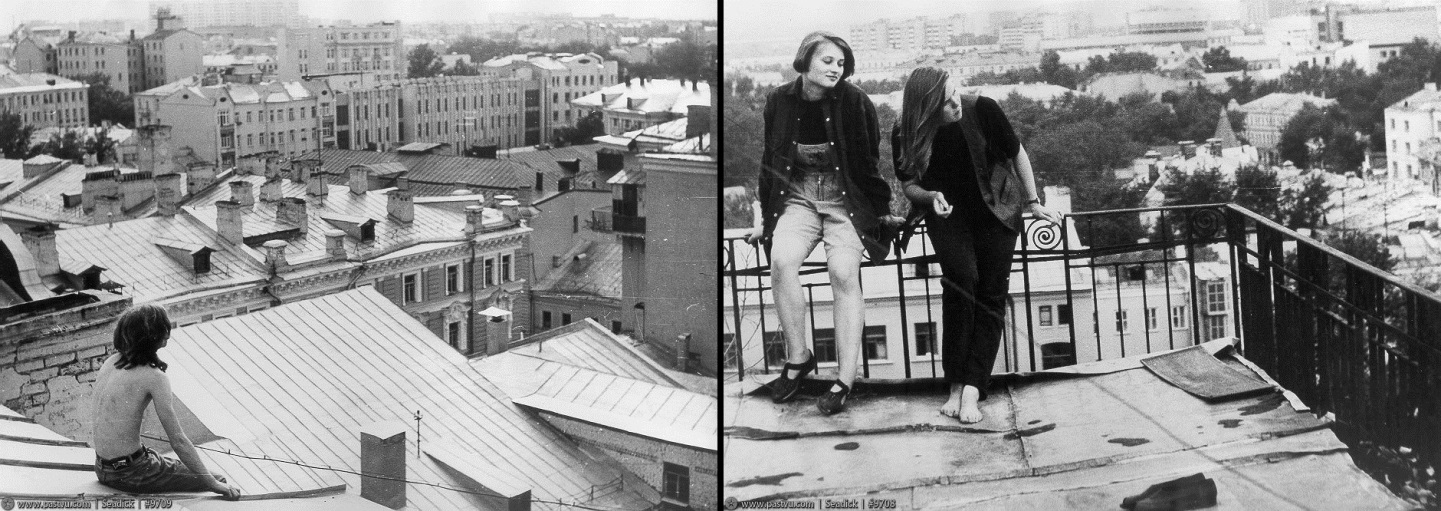

With the Moscow authorities’ acquiescence, the district has turned into an aloof and inanimate part of the city. Unintelligible post-soviet architectural and planning concepts left no space for outdoor activities, local businesses and even green spaces. Barely any new ambiance was reintroduced to this area after the loss of its entire population and architectural appearance. It is unclear whether new local tenants were eager to have a lot of services at the ground floors, but unregulated developments have created a dense elite enclave that is reminiscent of nothing but the outskirts’ bedroom communities. The whole district still lacks the most basic thing that was destroyed in the 90’s: livability. Despite the poor living conditions in socialist Ostozhenka, the area used to be famous for its authentic Moscow spirit. One could stroll for hours in the trees-shaded crooked alleys of this serene neighbourhood, looking for the shortcuts between the streets using the inner courts and backyards of the 19-century mansions.

Regular gentrification features a conflict between economic benefits and negative social outcomes at the district and city level which make the process rather contradictory and complicated. The Ostozhenka case is less paradoxical. It witnessed the early phase of post-socialist urban development processes. What happened next, however, only brought losses for the city. Complete population displacement was followed by a barbarian redevelopment stage which completely altered the district’s visual and social makeup. At the next stage of the real estate price alterations that usually push the existing inhabitants out, there was simply no-one left to expel. Nonetheless rents rose high enough to prevent any single venue or business appearing in the district.

Moscow’s economy, that should have benefitted from the process of gentrification, has lost a valuable historical, architectural and touristic gem and asset. Complete demolition of the dilapidated historical Ostozhenka and subsequent redevelopment without following any logic or framework isn’t the answer to the demand for high-quality urban space. Neither does it solve social issues. Even those new business elites that had been looking for a luxurious place to live, were swift and accurate in their evaluations of the project – anemic streets and idle flats are not likely to turn into a functioning neighbourhood soon. The windows of the houses are currently coated with a layer of dust and dirt. Most of those million dollar apartments are left empty by their owners who prefer to live in the cosier parts of Moscow. Luckily for them this real estate has turned into a very valuable asset. The only definite winners in Ostrozhenka are the unscrupulous developers, generating super profits, arguably (but most surely) split with corrupted city authorities.

What was happening in Ostozhenka is often regarded as gentrification and although it recalls that phenomenon, that is not what it is. In contrast to classic gentrification, Ostozhenka’s ‘renaissance’ was launched by developers that have promoted the area, which had nothing to do with the stereotypical ‘bobo’, ‘urban pioneers’ or ‘yuppie’ intrusion. The fact that Ostozhenka was suffering from disinvestment wasn’t really special in a post-socialist city where the quality of the urban environment had been overlooked almost everywhere. The following processes haven’t put the area on the map and nor have they introduced a fancy tertiary sector. On the contrary: it created an anaemic investment space. Finally, the city (not some particular city officials) has never had a single chance to profit from this displacement in Ostozhenka, thus making it completely nonsensical. It’s not gentrification that has happened – it’s an extreme form of rampant plutocratization that we observe in the very center of formerly ‘classless’ Moscow.

Ostozhenka – or rather ‘the Golden Mile’ as it is known nowadays – has gone through a set of fascinating changes in the past 20 years. The area’s appearance and population structure has changed completely – thanks to the uncontrolled urban growth and displacement – but one trait has remained the same: Ostozhenka is a neglected area of Moscow. But what used to be the governmental negligence, leading to superficial dilapidation in Soviet times, was replaced with the disinterest of the area’s new inhabitants – a pervasive process which has cut off one of the most beloved parts of Moscow from the cityscape. Those sumptuous houses don’t just form gated communities in the very heart of the city, they also scar the city: leaving not only Ostozhenka’s streets empty, but also its luxurious new apartments.