Beirut is a city full of contrasts. Not just when it comes to cultural diversity and unstable political situations. Also in terms of architecture and urban planning there are diverse influences such as economic perspectives and historical layers which are responsible for shaping contemporary Beirut and thus feeding ongoing discussions among planners, architects, politicians and citizens. It seems that there are quite different opinions especially on the question of how to deal with Beirut’s cultural heritage in terms of restoring, reprogramming, reusing or simply demolishing.

After a quite liberal and prosperous time in Lebanon in the 1960s, the country was hit by a civil war in 1975 which ended in 1990. When we recall the images of post-war Beirut in the 1990s there are lots of damaged buildings, war ruins and deserted city strips. Now after more than two decades of planning, developing and rebuilding Beirut, there are still war-scarred buildings in-between investor identified new developments.

Right in the spotlight of the city’s constant discussions on preservation versus demolition, there is a building situated in the center of Beirut, which is still abandoned, war-scarred and which behaves very strangely in the existing urban fabric. The whole plot, where the building is located, is owned by a private post-war investor, who is in charge of developing a significant part of the current city center area. Within Beirut’s society this whole planning situation in the city center is regarded as very controversial. Knowing the fact that one private company is in charge of developing free and open public spaces in downtown Beirut is a critical one.

Through internet research you’ll find very odd labeling for this building. Among the local people it is commonly nicknamed ‘The Dome’ or ‘The Egg’. After closer investigation you‘ll find out this is not just an abandoned brutalist building, planned to function as a bunker or a water tank. Rather, it was planned for cultural purposes, namely to be a movie theater.

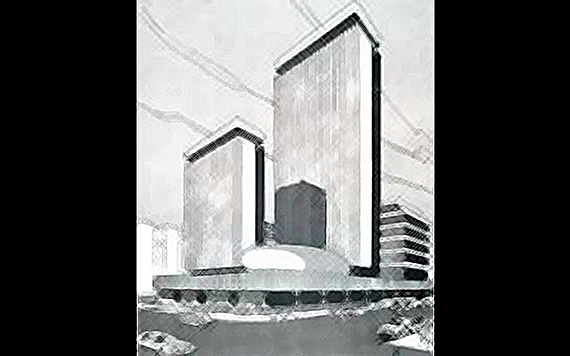

The Egg itself was commissioned as part of a modernist set of buildings in 1965, designed by the Lebanese architect Joseph Philippe Karam (1923-1976). The whole set was thought to be the ‘Beirut City Center’, a multi-use complex, which concentrated mainly on the hybridization of two programs: spaces for leisure activities (shopping mall, cinema) mixed with office spaces. Now when you look closer at the drawings of the original project by Karam, The Egg is more or less an unobtrusive part of the whole set of buildings, which consists of two high towers and the egg-shaped shell protruding from a large column supported plinth.

When the civil war started in 1975 the construction of the ‘Beirut City Center’ was still unfinished. Only one tower was built. But during several periods of war in-between 1975 up to 2006, the whole unfinished ensemble largely disappeared. The Egg and a large void for underground parking are the remaining fragments of Karam’s original plan for the ‘Beirut City Center’ that survived constant amputation due to urban warfare, bombings and further demolition of war-ruined parts commissioned by local authorities over the years. In the end the appearance of the remaining structure, nowadays known as The Egg, has shifted from being unobtrusive to eye-catching.

What you can see now in the city center of Beirut is more or less reminiscent of a bunker in the sense of Paul Virilio’s ‘Monolith’ – a massive structure which survived several attacks, but still stands and has since become a monument. Also it simultaneously recalls the brutalist architecture of Claude Parent, particularly the Church of Sainte Bernadette de Banlay in Nevers (France), but with scars, holes and other penetrations caused by constant instability. Finally the original planning for the ‘Beirut City Center’ transformed from being a clearly elaborated modernist set of buildings to a seemingly brutalist monument which is now perceived as The Egg due to its remaining iconic shape.

On a website dedicated to the work of Karam, you will find a description of his projects as follows: ‘One finds in his various works the revolutionary creativity of Le Corbusier, the fluid, more refined, formality of Oscar Niemeyer, and occasionally the brutal power of Kenzo Tange’. These are probably the stages the building encountered during decades of heavy disfigurement from the 60’s until now. It changed its faces, from being planned as a modernist building à la Le Corbusier and Niemeyer to a dark and brutalist appearance, which no one could ever have imagined.

The majority of local authorities, planners and architects would consider the current situation as failed. Many concepts and urban strategies have been considered for the site of The Egg, for example by Bernard Khoury and Christian de Portzamparc, just to name a few. But these projects are yet to be applied. Until recently the public had access for temporary use, especially for art exhibitions and clubbing events. But due to a decision of the current investor access has since been restricted through the use of fences and security guards.

While much of the formerly destroyed city center has been rebuilt or restored, it seems that the future of The Egg is still undefined. To date the recent project by Christian de Portzamparc is still fresh and the current investor envisions high class hotel and office spaces. Still, nobody knows whether the project will be executed.

Nevertheless for most Lebanese people this is just a further step in the direction of Beirut‘s way of dubaization. This is one of the reasons why heritage activists protest against the further demolition of Beirut‘s built cultural heritage. It‘s the idea of being true to one’s own identity. A documentary project by Lebanese artist Aimee Merheb called “Saving the Egg“ intensifies this call for respect using the example of The Egg. In her video she is literally in search of the importance and the emotional value of the war-scarred structure by interviewing a contemporary witness and a cultural heritage activist. And sometimes it can be as simple as that, like one activist is saying: ‘People can‘t explain it, they just love it’. The value of The Egg as a monument is quite high and at the end maybe higher than economical profit.

In a case like this it’s very hard to decide whether the ruin should be demolished or restored. And if restored, which program is going to be applied. Either way something will get lost in the process of planning. Except if there is a way to inherit a program for classless public needs and a subtle and rough design approach to apply the new program on the site. Because fact is: a rising city like Beirut won’t be able to keep abandoned spots in the downtown area like The Egg untouched for much longer.