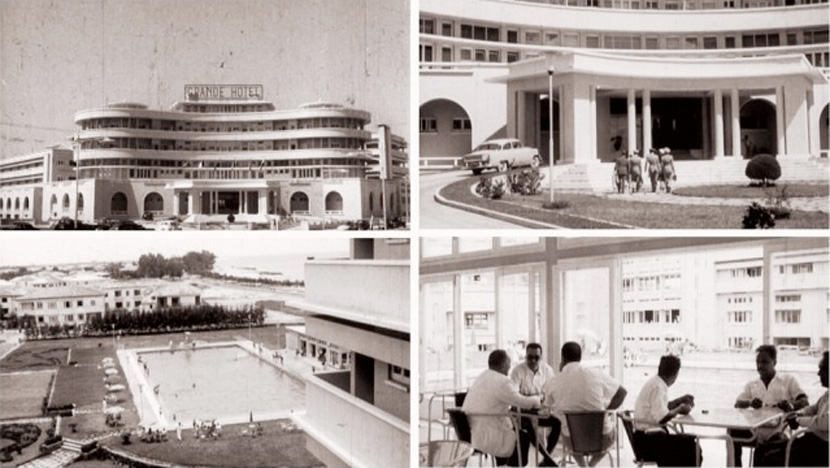

Inside the quiet Ponta Gea district of Beira, Mozambique sits the Grande Hotel. A relic of luxury marking the cosmopolitan era of 1960s Portuguese colony, it now stands as another of the country’s concrete modernist ruins. Architecturally, the building was notable for its impressive concrete spans, its fluidity, and its overall size, marking out the ingenuity and idealism of the young architects emerging from the 1948 CIAM congress. All this, however, has been overshadowed by an unexpected use that has been found for the hotel. The once grand building now hosts one of the largest communities of squatters in the country, 2500 residents who have garnered the attention of a multitude of press, the photographer Guy Tilim and inspired a film by Lotte Stoops.

A Country Abandoned Overnight

Mozambique gained official independence from Portugal on June 25th 1975. After ten years of armed struggle, the country’s former Portuguese inhabitants fled from the cities, abandoning their homes, offices and civic buildings almost overnight. The cities became ruins as soon as they left, ageing rapidly under both the tropical climate and the strains of a twenty-year civil war.

Lining all of Mozambique’s major cities you’ll find these examples of modernism, from art deco to brutalism, still retaining almost all of their original features, from furniture, fittings and switches down to what in many cases looks like the original paintwork.

But the buildings are so untouched, so completely preserved, that it almost goes beyond simple negligence. Instead, it suggests a possible unspoken detachment from a nation struggling to adopt the abandoned ruins of another. That is not to say that Mozambicans are not right to preserve what are truly beautiful examples of modernism, indeed such preservation is to be commended. Yet this steadfastly stoic treatment of the urban environment amounts almost to an expression of natural detachment from a city made very much for another people, a city which still carries this memory of the vacant owners.

This remarkable ruin was first revealed to me through the photos of Guy Tilim, on show in the National Portrait Gallery. The photographer himself notes; ‘How strange that modernism, which eschewed monument and past for nature and future, should carry such memory so well’. Given over to the haunting nature of desolate cities, dominated by the presence of these concrete monoliths, I was overcome by ruin lust; seduced by the familiarity of modernism transformed so beautifully by nature. In reality, this disconnect is harder to see in the major cities of Mozambique whose inhabitants seem to live happily and comfortably in the modernist relics, unaware, or rather unfazed, by any sense of abandonment. Even so, there remain instances where these ideas of displacement and detachment resonate clearly. Moreover, it is with this detachment that people are able to understand and alter the buildings in a completely new way, unencumbered by any nostalgia or reverence and still retain the melancholic beauty that characterises many of the modernist buildings in Mozambique. This is the case with the Grande Hotel.

The Grande Hotel

The Grande Hotel closed 10 years before independence in 1965 after it became clear the project was not financially viable. Following this, and in light of the war for independence, the FRELIMO (the Mozambican liberation movement) moved in. Some of these original settlers still live in the building today, with many of their grandchildren now occupying the rooms they have come to call home. Alongside these original settlers are migrants who arrived during the civil war. Displaced during this period, they came to the hotel, which by this time had already developed into an informal settlement.

Today new arrivals still come and not always out of necessity. Indeed, I was told when visiting that a more recent inhabitant is a university student studying in Beira. Over time these settlers have manipulated the structure and make-up of the building to accommodate their needs and livelihoods.

Designed by the architect Franciso Castro as a grand tourist hotel, with the country’s first Olympic pool, cinema, ballroom and even (unrealised) plans for a casino, the building came clad in beautiful fittings and fixtures, large panels or glass and a staircase comparable to ‘Gone with the Wind’. The hotel’s first settlers began the initial stripping of the hotel, selling these furniture fixtures and fittings. Now, the building’s bare concrete is pocketed with crevices and holes from where metal fixing and even cables and pipes have been removed from the structure and sold. In fact, the removal of glass, wood panelling, and ceiling panelling has left no ornamentation remaining. For many in Beira, this destruction of the original space has resulted in a negative portrayal of the hotels inhabitants, with many referring to the community as Watha muno, meaning ‘one from there’, or rather not from here (Beira). This, coupled with the violence and crime reported in the area, has led many in Beira to steer clear of the site.

But the building is often a hostile environment for the inhabitants themselves, not least because of the rigid limits of the concrete structure. For instance, the hotel has little tolerance for the vernacular practices many of the inhabitants bring with them. This includes the traditional Mozambican practice of machambas, a sort of allotment on which most people farm their own crops throughout the year. The large mass of land surrounding the hotel is now filled with machambas, growing local crops such as xima and matapa. Unable to encroach on the concrete flooring, some even use the small cracks in the roof to grow tomatoes, thus raising the question of whether the ratio of dwelling to land is sufficient. At times the building also appears to cause a social barrier due to its inflexible compartmentalization, meaning social activities such as cooking and washing, normally undertaken in the open veranda or garden, are now restricted to the confines of the internalised private realm of the balcony or darkened room. This leaves some residents to express a new sense of loneliness commonly associated with city living. Most upsetting though, are the failings brought on by the lack of barriers in the place where lift shafts are now empty and where staircases are damaged and walkways left open. When visiting I was told a three-year-old child had fallen two stories from an open walkway and died. Unlike the violence and crime, which could be attributed to any area of poverty, such incidences highlight the dangers inherent in a modernist ruin, a concern made all the more pressing by the building’s increasingly precarious structural state; a local architect Senhor Ivo questioned the likelihood of the building being allowed to stand for much longer, given its need for structural reinforcement.

Re-imagining the Space

Despite these failings, the hotel’s community has brought some beauty to the state of the building, a beauty that is overlooked by its critics. Through their manipulation and use of the space, we, as architects and planners, can distinguish a unique revival of a modernist ruin at the hands of the people. As is often the case with informal settlements, those with such a vernacular knowledge have the ability to build and live in a way that suits them almost immediately. Although the failings are obvious, it is still intriguing as an outsider to witness people using a building as freely as they would on the landscape beyond the city. Inside the hotel, many have built up their home almost overnight. In the hotel’s enormous hallways are homes built from a combination of concrete blocks, woven reed, timber and corrugated steel. Not put off by the conventions of tower blocks, inhabitants have even claimed stairwells and landings, with one stair-dweller visibly pleased by the home he had managed to build for his family overlooking Beira. In this way the hotel has begun to shift from a formal building, to a ‘concrete landscape’, to be as freely used and torn up as the land set outside of the city.

And despite the creeping sense of alienation mentioned above, more positive social practices have developed, practices which reveal a sense of community spirit clearly at odds with the stories of crime and violence. These include the block leaders who overlook the running of the hotel and provide help and advice for their respective dwellers; market stalls dotted around the main the entrance, but also in block corridors higher up, suggesting a sort of ‘streets in the sky’ set up; and outside, on the grounds, a church, a mosque, a school and enough space for games of football.

In the de-cluttering of forms and materiality, there is also a purer expression of the true form of the building, now unencumbered by its former fixtures. As an architect of the 1948 Congress, Castro would have been indoctrinated into a liberal, possibly utopian way of thinking and designing subverted to suit the context of fascist Estado Civil. The stripping of the building exposes these intentions, revealing beautiful walkways and striking voids reminiscent of Park Hill. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Guy Tilim’s most beautiful photograph of the Grande Hotel is of the stripped out concrete staircase, covered only in the light from the unglazed windows above in an almost pure expression of brutalism.

The predicament of the inhabitants is a sad one, and indeed perhaps the hotel is not as welcoming as the porous natural land outside of the city. However, in present-day Mozambique is it not feasible to consider adopting the working class into the existing frame of the city? If desolate concrete ruins are the only spaces where immigration can take place, why not leave these beautiful ruins and allow such adaptations to blossom responsibly? This is not an argument, but rather a new exploration of a very small and unique fraction of modernist ruins in Mozambique, a country deeply overlooked in the wider discussion of modernism today.

As outsiders though, and especially in the west, we could use the dramatic relics of Mozambican modernism as a new example of beauty in the modern ruin. Here is an example where time and destruction have been fast-forwarded into a situation only imaginable in a post-apocalyptic fiction. More importantly, they have been altered by means we would never attempt; that is, by the everyday man, using vernacular techniques on a large scale.

With the absence of engineers, and architects, the reality is that the lifespan of the ruins is nearing complete destruction, unless as Senhor Ivo notes, funds are obtained for basic repairs. However, what remains is still strangely beautiful at times.

All ruins are freighted with possibilities. This is a new one.