A café awning in central Budapest reads “things of the past live always with us.” While the establishment is quiet, filled with tourists devouring goulash, that maxim is playing out in real-time just down the street, in Freedom Square (Szabadság Tér). There, Hungary’s turbulent twentieth century history is being interpreted and reinterpreted in fraught conflicts over which monuments should occupy the plaza.

The symbolic debate has been conducted in and around that space since the fall of Communism, with a memorial to the Soviet Red Army, a bronze of Ronald Reagan and other monuments vying for pride of place. The jostling has accelerated this spring, as demonstrators forcibly delay construction of a government-backed World War II memorial that symbolically depicts the German invasion of Hungary. Local and international Jewish groups, as well as Israel, say the planned monument fails to acknowledge Hungary’s complicity in the mass deportation of its Jews. The government has erected protective barriers around the construction site but protestors keep pulling down the fencing.

In 1991’s flush of freedom from Soviet domination, local councils voted to exile most of Budapest’s Communist monuments to a kitsch “statue park” on the outskirts of the city. Though Hungary joined the European Union in 2004, the mélange of statuary in Freedom Square reflects the nation’s ongoing struggle to define a new identity.

Under the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (1867-1918), Hungary experienced a golden age. But World War I resulted in bitter defeat and with the collapse of the dual monarchy and the peace settlement known as the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost about two-thirds of its historic territory and a comparable portion of its population. By 1920, Admiral Miklós Horthy had re-established Hungary as a kingdom, and a nationalist quest to reunite this “Greater Hungary” defined his rule. That year, his government erected a slew of statues meant to mourn the lost territory of Trianon in the same square where protestors are battling the government today.

Horthy is also the ruler who, in the lead-up to World War II, allied Hungary with the Axis nations. That partnership was made official in 1940, but later Horthy regretted his decision and began negotiating with the Allies. Consequently, in March 1944, Germany invaded—though it allowed the Horthy government to remain in office. It was in this complicated political context that Hungary deported 437,000 Jews, who were later murdered in Auschwitz. When Horthy tried to disengage from the war again in October, the Fascist Arrow Cross Party toppled his government in a Nazi-backed coup.

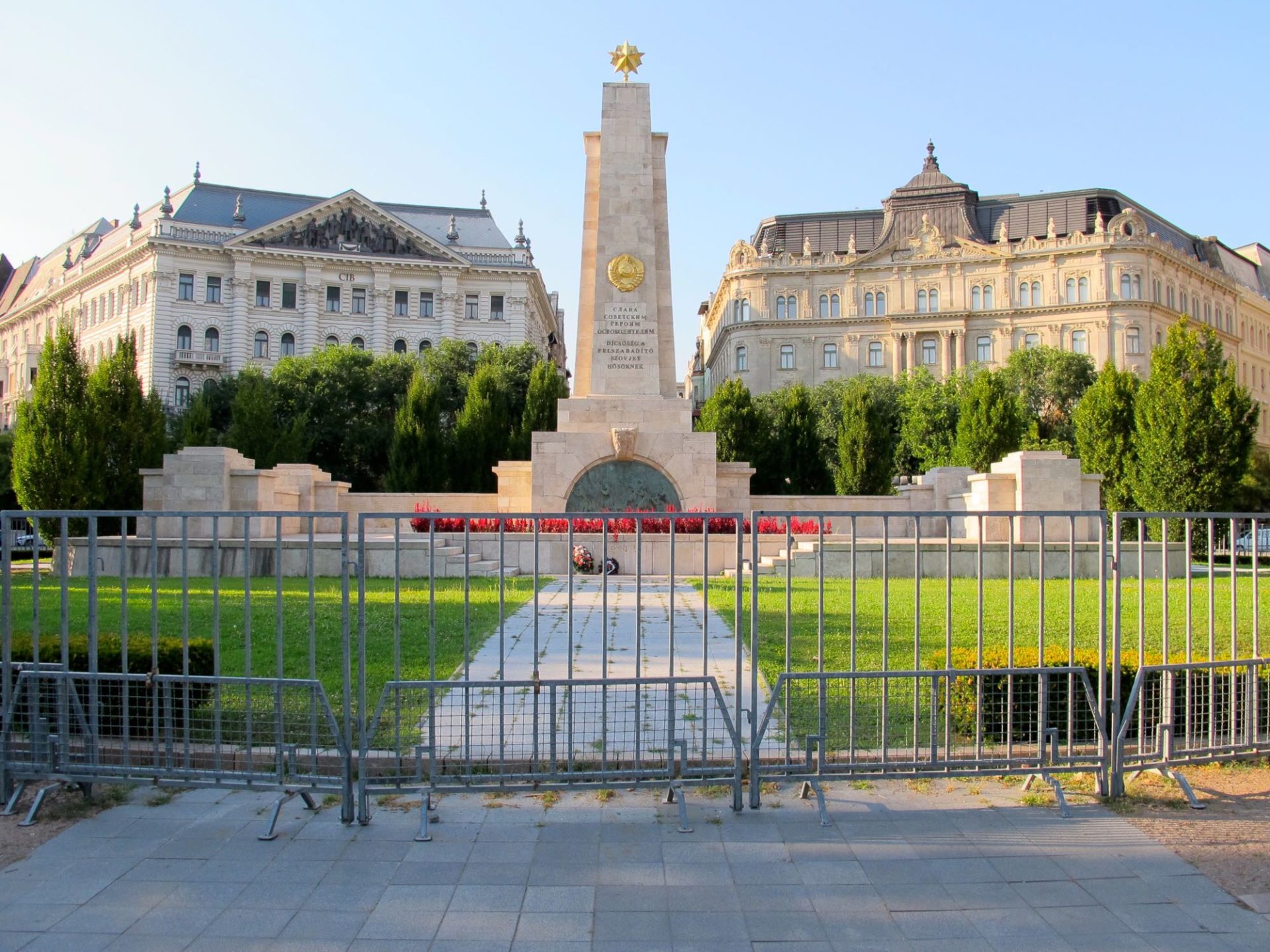

The Arrow Cross did not last long. World War II was coming to a close and by April 1945, Soviet troops had taken Budapest. To mark that change of politics, the Soviets cleared Freedom Square of the Horthy-era structures and erected a large obelisk topped with a Communist star, in honor of the Red Army’s “liberation” of Hungary. Protected by a bilateral treaty between Hungary and Russia, that monument remains the centerpiece of Freedom Square today. It is a source of contempt for many locals, who view the Soviet “liberation” as the beginning of decades of imperial subjugation.

In the 1990s, an array of groups sought to dilute and alter the obelisk’s meaning by strategically placing monuments of their own in its periphery. Most notably, in 1996, real estate tycoon Sándor Demján provided the funding for a statue of the hero of Hungary’s anti-Soviet 1956 uprising, Imre Nagy, to be erected between Freedom Square and the Parliament at a plaza called Martyr’s Square (Vértanúk tere). Nagy stands on a bridge over an artificial pool of water. With his back to the Soviet monument, he gazes toward the looming neo-Gothic parliament building, an emblem of Hungary’s new democracy. This major tourist attraction allows visitors to mount the bridge and walk toward freedom.

But some still wanted the Red Army memorial gone for good. The monument was subject to a series of vandalism attacks in 2006, causing the government to install protective fencing and assign a police watch. The following year, a right-wing group called the World Federation of Hungarians set up its own monument nearby, in the form of a protest tent. Signs on its exterior called for the removal of the Soviet obelisk and the re-erection of the irredentist monuments of the Horthy era.

Hope for that cause was re-invigorated in 2010, when the Federation of Young Democrats (Fidesz) came to power with a super-majority in parliament, led by Viktor Orbán. Originally the liberal, youth wing of the anti-communist opposition, the party has markedly shifted to the right. While it is still anti-communist, it is now also known for its anti-democratic tendencies. After its electoral victory, the Fidesz government pushed through an advantageous new constitution, in a move that was criticized by international rights watchdogs and western governments alike.

Outflanking Fidesz from the right, at the same time, was a growing nationalist extremism. In 2010, the Jobbik party came in third, gaining 17 percent of the vote. Its platform paraded the ideology of the bellicose Horthy era, with its territorial demands on Hungary’s neighbors and overtly racist policies. Jobbik demanded the Red Army memorial’s removal.

That put Fidesz in a sticky position. In reference to the monument, the Russian ambassador to Hungary had previously warned that “bad political relations impact economic relations.” Indeed, when Estonia removed its own Soviet war monument in 2007, Russia responded with a barrage of informal sanctions–a clear illustration of the lengths to which Vladimir Putin might go if Hungary were to make a similar move. Fresh in Fidesz’s mind was its experience the previous winter, when Russia cut off natural gas to many of the former Soviet bloc states, including Hungary, in a play many perceived as political.

Unwilling to risk the consequence of removing the monument directly, Fidesz resorted to the time-honored tactic of building a monument with contrary meaning nearby. In the summer of 2011, a larger-than-life Ronald Reagan, a popular figure among Hungarians for his hard line against Communism, was unveiled. Up the street, Imre Nagy has his back to the obelisk; Reagan confronts it head on. With a forward stride, he looks as if he is about to walk through the structure and on to the American embassy on the other side.

The far right has since abandoned its protest tent. Instead, in 2013, it too decided to add a new monument to the plaza. A bust of Admiral Miklós Horthy was presented at the entrance to the Hungarian Reformed Church, which sits on Freedom Square’s edge. The church was once run by a nationalist clergy associated with the Fascist Arrow Cross, and is now run by a clergy associated with Jobbik. For obvious reasons, the Horthy statue does not sit well with Budapest’s minorities and more liberal factions of society. Its neighbor, the American Embassy, described the bust as “shameful.”

Freedom Square keeps getting more and more crowded, and the structures increasingly controversial. Historic disputes are now coming to a head in the latest symbolic quarrel, over the new monument that depicts the Nazi occupation. In 2013, Hungary declared 2014 to be a year of Holocaust remembrance, to mark the 70th anniversary of the 1944 deportations of Jews. The government planned a memorial, but representatives of Budapest’s Jewish community were notably absent from the process of choosing a design. That led to the monument that is inciting protest today: A German eagle descends on the Archangel Gabriel. The clear meaning it that Hungary was a simple victim of Nazi aggression. In a re-writing of history, Hungary loses any culpability for expelling Jews.

While the unveiling of the monument was originally to occur in March, Orbán delayed construction until after the country’s national elections on April 6th. Fidesz won by a landslide and Jobbik again came in third, this time with an even greater share—20 percent—of the vote. Construction on the monument began two days later. His power affirmed, Orbán is now more fully supportive of Jobbik’s attempt to re-imagine, some say whitewash, Hungary’s relationship with Hitler.

What’s more, Orbán is simultaneously reshaping Hungary’s approach to Putin. As relations between Hungary and the E.U. deteriorate, he has pursued a policy of “opening to the East,” looking to less democratic polities like Russia for partnership. On a May 2013 visit to Budapest, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stopped at the Red Army memorial, where the fence was temporarily removed so that troops could lay a massive wreath. Later, Lavrov met with his Hungarian counterpart János Martonyi to discuss plans to complete the “South Stream” natural gas pipeline, which will traverse Hungary and is slated to open by 2017. Unlike many of its neighbors who demand tough sanctions against Russia in response to the crises in Ukraine, Hungary’s own stance has wavered.

For now, it seems likely that all of Freedom Square’s monuments, with their duelling messages, are here to stay. Freedom Square provides a lens into how Hungary is reckoning with its Soviet-dominated past, but it also provides ominous portents of the right wing nationalism that is growing in strength today.