With words such as ‘organism’, ‘cell’, ‘fabric’ and ‘regeneration’, Japan’s Metabolist movement articulated a distinct and idiosyncratic aesthetic for their projects and defined a new architectural vocabulary.

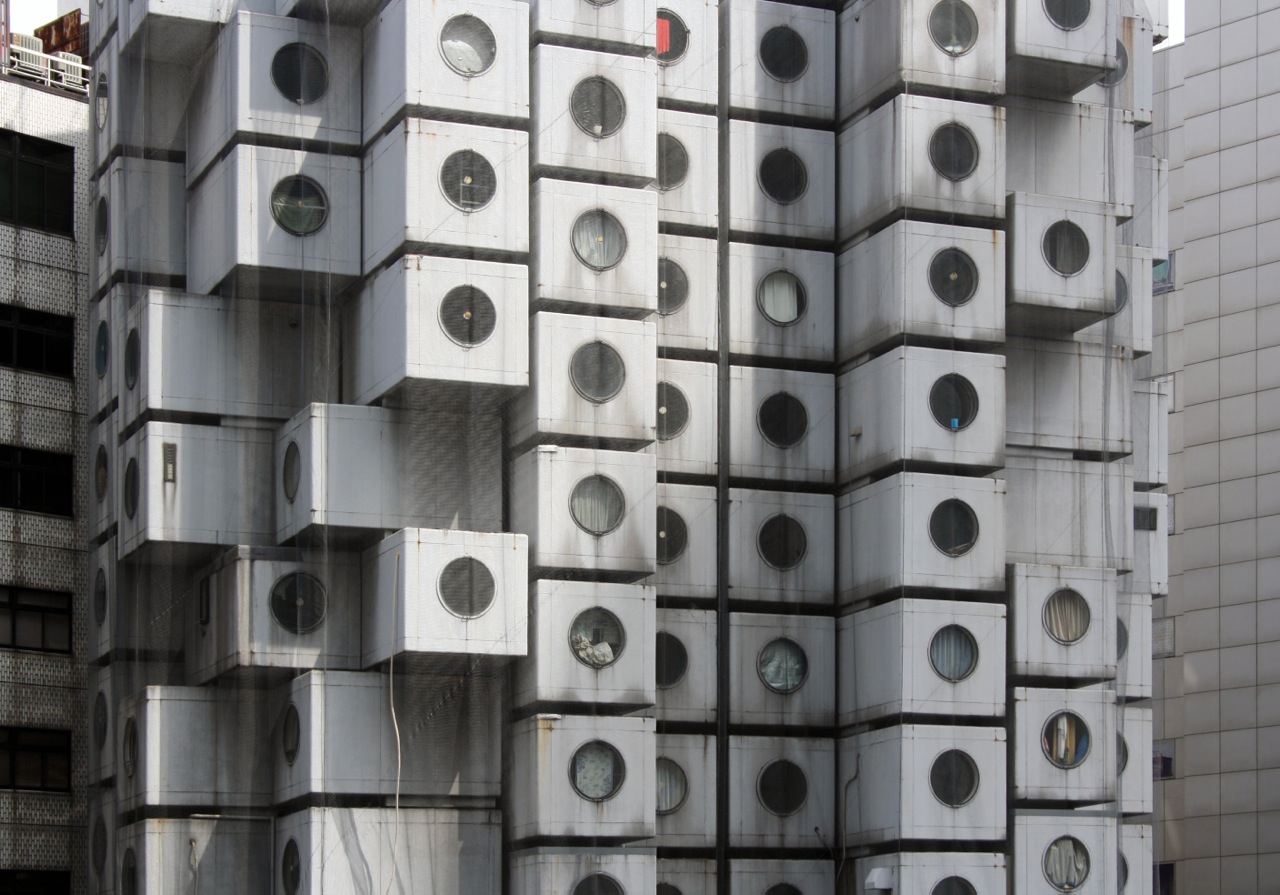

Tokyo’s Nakagin Capsule Tower is an exemplary expression of this vocabulary. However, from the moment of its completion in 1972, the utopian structure was a fascinating yet wholly anachronistic remnant of a past future, struggling to survive. In 2013, we had the opportunity to live there for almost a year, to share the experience of everyday life in the building with its remaining residents.

Flagship of a Metabolist future

Metabolism’s rise and fall are bookended by two important events a decade apart. Its first manifesto dates from 1960 and marks the genesis of its theoretical formulation. Ten years later, theory evolved into practice with the Expo70 in Osaka. The event’s significance went far beyond the movement and came to be seen as an important moment in the definition and understanding of contemporary Japan.

A late arrival, Nakagin represented the last opportunity for the realisation of the movement’s ideas. As such Kisho Kurokawa, the building’s architect and one of the founders of the movement, took the opportunity to sculpt an ideal. Unfortunately (and unsurprisingly) he could only build it on a scale much smaller than the theoretical projects he had previously developed. While the movement of the façade, the proportion of the base and the top of the cores were designed to shape a form that was natural and organic, in fact this was only in theory. In clear conceptual contradiction, the architect stated publicly that each inhabitant would contribute to the construction of the building’s identity, but in reality it was he who merged all the decisions.

And while it was presented as the house of the future, the capsule design was in fact based upon the interpretation of several references and traditions from Japanese culture. The area calculation was derived from the size of a traditional tea ceremony room. The shape and proportion of the window were a reinterpretation of the ‘Enlightenment Window’ from Kyoto’s Genkoan Temple and the life cycle suggested by Kurokawa was a direct allusion to the Ise Shrine, rebuilt every 20 years. The furniture was supposed to be built with slight, avant-garde and innovative materials. Instead, less technologically demanding lacquered pinewood was used. And even with such limited space, the bathroom was designed with a traditional bathtub. The apparatus of the Nakagin hides its references: the proclaimed Metabolist future fed off an interpretation of its past.

In 1972 the Nakagin Capsule Tower was portrayed in the media as a sign of ‘the capsule era’. With its avant-garde aesthetic, it proposed a mutant quality, offering the opportunity of adaptation over time. Theoretically, it increased the ability to configure the building to a world accelerating towards a post-industrial society; the icon was quickly labelled ‘the future of housing’. It was the tallest building in the block. Visible from afar, with its sci-fi appearance, the tower stood near the highway like a machine from the future. Its architect, Kurokawa, was proclaimed a star and it was assumed that many other examples of Metabolist architecture would eventually be dotting the Tokyo skyline.

Yet even before it was completed the Nakagin Tower was hopelessly out of date. It is in the unfortunate position of being the first and last architecture of its kind to ever reach completion. Forty years have passed and today it is easy to see how the building got lost in dull day-to-day routine. It is stuck. Old and decaying, obscured in the shadow of the new skyscrapers. Today the Nakagin is but a vibrant reminder of a path that was not followed, a sculptural ode to an unrealised future.

Experiencing the dreams of the past

To wake up in a capsule (Capsule B807) is to wake up in a place unlike anywhere else. There is a bed, a window, clothes everywhere and the sound of morning traffic. However, there is also something less tangible, something that makes every waking moment special. Maybe it’s the brilliance of the great round window or the quiet charm of the table, sometimes open and covered with junk, other times closed and silent. Maybe it

’s the door of the bathroom, appearing as if an entrance to a submarine. Or maybe it’s the scale of the room, a scale that seems just about right. Every morning brings a happy sense of the sublime.

As architects, we spend years studying the most remarkable buildings: their plans, sections, ideas and ideals. However, living in one of these ‘examples’ was different. To live there was to live as an active part of the books of history and theory, but to be only dimly aware of such a wider significance.

For those units that maintain the original design, ergonomics is total: 35 cm in depth, a cabinet covers one of the walls and provides storage for the entire capsule. It’s a bookshelf, a dining table, a closet for clothes, a set of trap doors to other objects and space for hanging jackets. The table rebates off when not required, and it is relatively low, like the sink. The capsule is filled with small details that, in a very simple and almost unnoticeable way, enhance the capacity to live in the capsule. The TV occupies its own detached shelf. In a few capsules, the original radio still works. The fridge is small and tight, like a minibar (unsealed), and the freezer doubles as a cooling unit.

The window is large and circular, and in a space with those dimensions, it proves to be very generous: there is a clear willingness to increase the relationship of the interior space with the city. The frame is fixed, to prevent accidents, but ultimately impedes natural ventilation of the room. All the surfaces are in contact with the outside and the result is simple: summer is too hot and winter is too cold. There is a huge space for the integrated ventilation system on the original design of the capsule but unfortunately, it can’t be used because of contamination.

The bathroom is even more ergonomic. The walls are made of washable plastic, turning the space into a capsule inside the capsule. As an interior space without any windows to the outside, the door has a round frosted glass opening to bring in natural light. Even with such a small space, there is a tub instead of a shower. Together with the toilet and sink, it forms one plastic piece functioning as a whole and organizing the space. The soap dispenser, lamp, towel holder and small shelves are subtly placed on the walls, avoiding the need for a cabinet.

The space inside the capsules doesn’t feel that small, in fact, its size seems irrelevant: the capsule fulfils the modern function of a ‘machine for living’, and even for a couple it allows for a very normal routine.

Falling apart

The Nakagin Tower is divided into two vertical access cores with 68 and 64 capsules, respectively. The cores are made of concrete; the individual units are suspended by a system of metal beams and cables. The ground floor is composed of a large atrium and a convenience store; the second floor is a traditional office complex. From that point, the spiral stairs reveal just the doors of the 132 units. The lifts work perfectly and are subject to regular inspections. Every day, in the morning, an old man cleans the stairs and common areas with a damp cloth.

But the building is decomposing and the few capsules that turn on their lights at night reveal its fate. There is almost no maintenance and the building was recently covered with a protection net after debris started falling onto the surrounding sidewalks.

In the construction phase, each unit was isolated with a 3 cm layer of asbestos, which today prohibits the use of the ventilation system built into the capsules. Hence, today this layer is almost useless and the capsules suffer huge temperature variations. Only with the aid of a strong heater and a modern air conditioning unit can the inhabitants withstand the temperature fluctuations.

The formatted nature of the capsules has prompted the residents to appropriate them in different and curious ways. In the original project the window blinds were made of Japanese paper, and only lasted a very short time; no capsule still has them today. On the outside one can see the various alternative solutions that the residents have found to fight the excessive light inside during dawn and even to create some privacy: curtains, clothing, sheets of newspaper. The exterior view also shows the ways in which residents have inserted secondary windows: some with the desire to create natural lighting in bathrooms, others to get the best sunlight or others still just for natural ventilation since the large round window is fixed. More than a third of the capsules have new air conditioners placed on the outside of their units, ‘decorating’ the building’s exterior.

The individual capsules don’t have hot water supply. For bathing, the options are either to get a water heater, or to use the communal shower on the entrance floor. Most residents opt for the second option. After the degradation of the pipes, a few years ago a new network of pipelines was installed. The rotted pipes have led to numerous leaks. Many of the capsules were thus unusable, rotting from the inside. Moreover, the renovation works were done without much care: doors were sawn into so as to pass and connect the new pipes. It seems that with every repair, the building falls into further disrepair.

On rainy days leaks in the corridors become visible in places where the joints of the units have eroded and the water flows freely through the doors. It is not unusual to see the doorman running down the stairs, spreading buckets in the most critical points.

Emergency exits were transformed into smoking rooms with ashtrays and chairs. Up the stairs you will find clothes hanging on wires, shoe cabinets, shelves with old and mouldy books, sets of boxes, huge suitcases, bikes and even fences around the doors. The balcony on the third floor, above the office level, is an abandoned platform. Dirty water and rotten capsule remnants are its sole contents.

More than half of the capsules are abandoned and many are ‘sealed’ from the outside, due to the risks they present. Others, however, do not even have locks and it is easy to enter and see the insides in varying degrees of advanced decomposition: walls are coming off and there is garbage, mould and moisture everywhere. From the emergency stairs on the outside, you can see that the capsules are slowly rotting.

Nevertheless, tourists love the Nakagin. Almost daily you see them flocking across the street, camera-crazy. Sometimes they try to get inside, but the doorman is well used to fighting them off. They then approach the inhabitants in the hope of visiting one of the capsules.

Living (the) ruin

Approximately 40 people live in the Nakagin Capsule Tower. Some of them use the capsule as a fixed address, but most use their space as a second address or office. Usually, the corridors are virtually deserted. Nevertheless, most of the remaining residents really want to be there, attracted as they are by its abundance of eccentricity. They all have a curious history and an emotional connection to the building. Several owners refurbished the old capsules, usually just on the inside. Some try to restore their units to their original state. In other cases, improvements have been made: air conditioners, wood floors, new bathrooms, and new windows.

Among the inhabitants, opinions about the future of the building vary. All expressed concern, but there was a troubling lack of consensus. As residents, it is even more difficult to be impartial and decide on what would make more sense for the future.

While interviewing the inhabitants, it became clear that the typology was considered a positive aspect. All highlight the few square meters available per unit, but none see it as a problem: it is the option that makes sense in a city like Tokyo. All agree that this is the condition of space that best serves the metropolis, providing a central and strategic location at the expense of a room or a garden – ‘the city fulfils that role’. To the inhabitants, the idea of replacing the units is out of the question. The economic investment and time required, and the clear notion that this would again be a temporary solution decreases the residents’ willingness to invest. The building regulations have also changed and at 41 years old, Nakagin has exceeded the point at which most buildings are scheduled for demolition (30 years) but is still far from qualifying as a subject of public interest (50 years). To many, it is confusing to accept that a building looking so futuristic could be considered historical heritage.

Ana Luisa Soares and Filipe Magalhães are the founders of fala atelier in Porto.