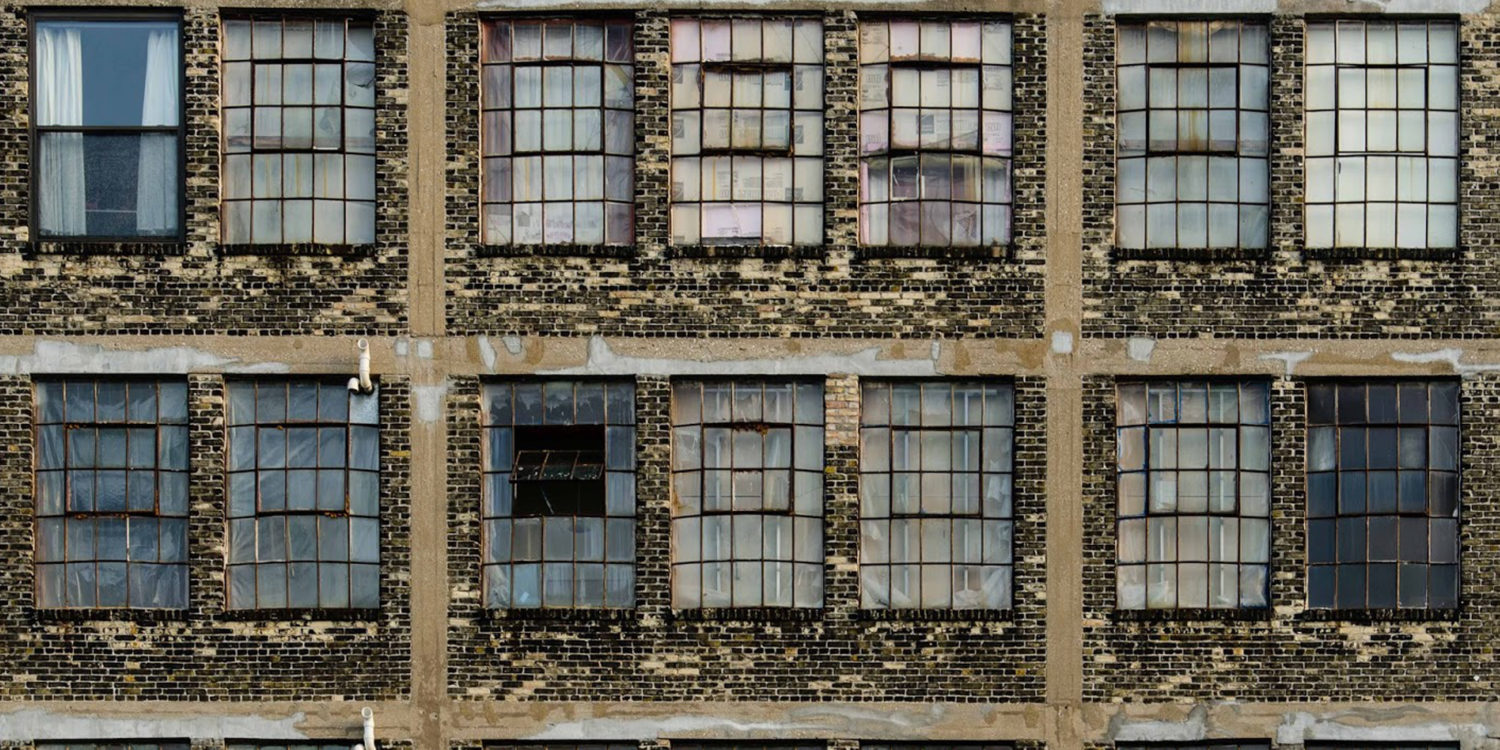

Because of economic shifts, changing tastes and other developments, certain buildings and building typologies become obsolete. Although sometimes aesthetically fascinating, the resulting vacancy is not only an eyesore to many, but also has a negative effect on the public domain, economic viability and other aspects of the city.

The financial crisis caused a lot of vacancy, partially because it exposed the perversities of the rapid flights of capital inherent in comtemporary real estate practices. But is has also proven to be a blessing to both the vacant buildings and local initiatives that surround them. In the absence of the funds to tear un(der)used buildings down and redevelop them, this extended temporary state provided a chance for both low-key and the more upscale, short and longer term reuses to flourish, experiment and diversify. Often, these new uses have proven to revitalise not only buildings, but also entire areas (sometimes even actively invited and subsidised by local governments).

Changes in economic structures also demand a new kind of spatial use. With more flexible economies, footloose and fluid workforces, and less capital-heavy industries, traditional approaches to the use of buildings have proven to be outdated. A well-known example is Amsterdam’s office stock, of which over one million square meters lies empty – seventeen per cent of its total – while the city’s economy is doing fairly well.

At the same time, vacancy in the Netherlands is dealt with in a peculiar way. In interim – ‘anti-squat’ or ‘vacancy management’- periods, property managers are hired to prevent buildings from being squatted and keep them on stand-by in order to be able to sell or develop them as soon there’s an interest. They do so by allowing people to rent spaces for very little money in exchange for a minimum of tenant rights. Not only can the tenants be given a two to four-week notice, they also don’t have rights concerning a.o. privacy, housing quality, complaints and participation in planning processes. Property owners and interim managers make use of the huge shortage of rental housing and work space, to get only a handful of people (often desperately looking for space) to rent huge spaces so that the properties are not vacant, while preventing the building from having a more meaningful programme in this interim period. Luckily there are people and organisations who are looking for alternatives to current approaches to vacancy and temporary use.

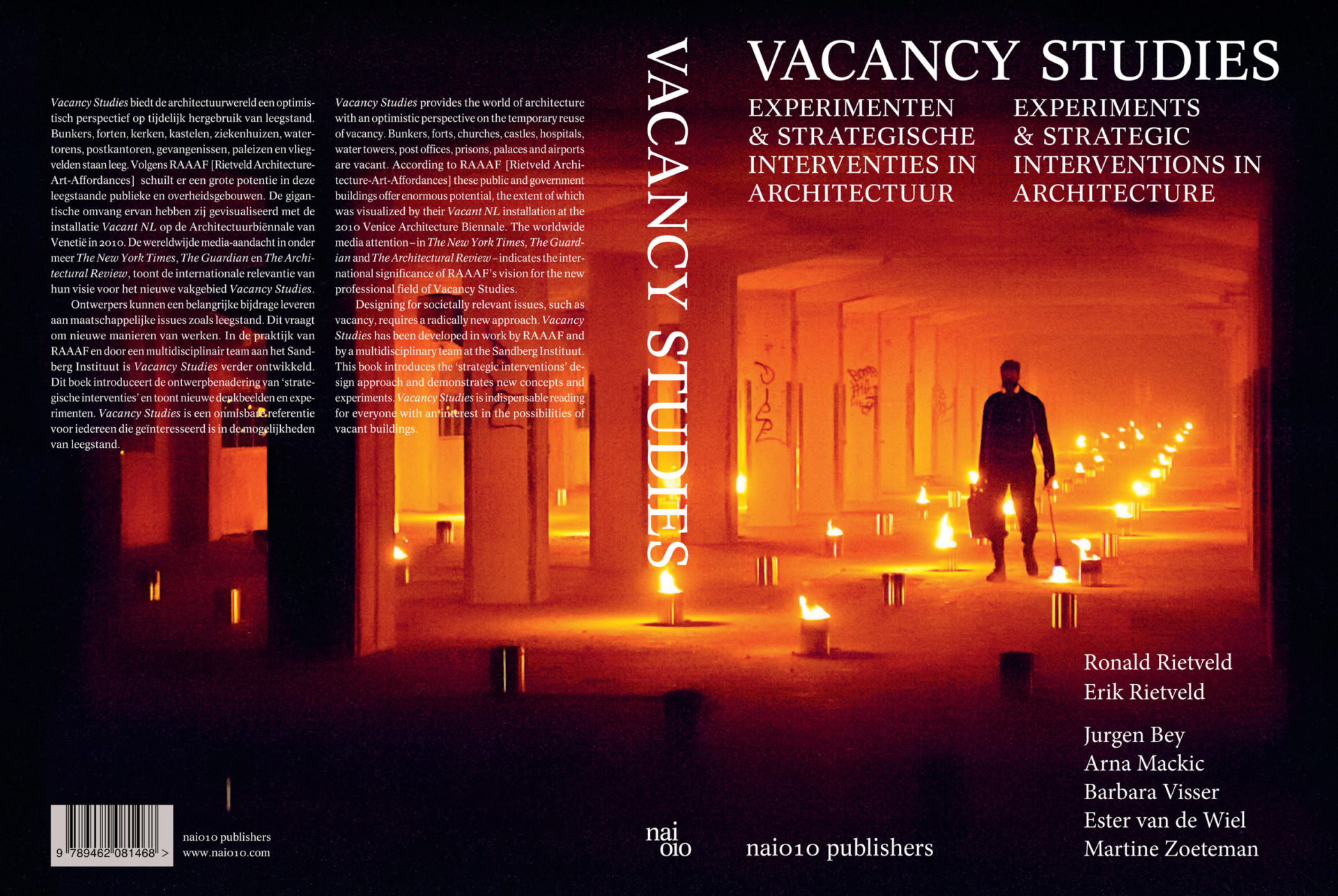

In the work of Amsterdam-based studio RAAAF [Rietveld Architecture-Art-Affordances], vacancy is a central concept, through research, design and intervention. In their newly published book Vacancy Studies: Experiments and Strategic Interventions in Architecture, they explore spatial, economic and institutional voids and their potential. With contributions by themselves (Erik Rietveld, Ronald Rietveld and Arna Mackic), tutors in their education programme, and artists, different perspectives on the potential of vacancy are explored. Of course, there have already been numerous books about reuse and architecture schools take the topic into consideration in their courses.

What’s refreshing about RAAAF’s approach, is that their strategies start with research, and that they are not in the first place – if at all – about architectural design. In some cases (in their own work and in that of their students) it is more about ‘designing’ new collaborations in the hybrid knowledge economy, insightful maps and inventories, or unconventional real estate lease models. Eventually concepts are built and tested 1:1. Moreover, their Master’s programme allegedly is the world’s first dedicated to the subject of vacancy.

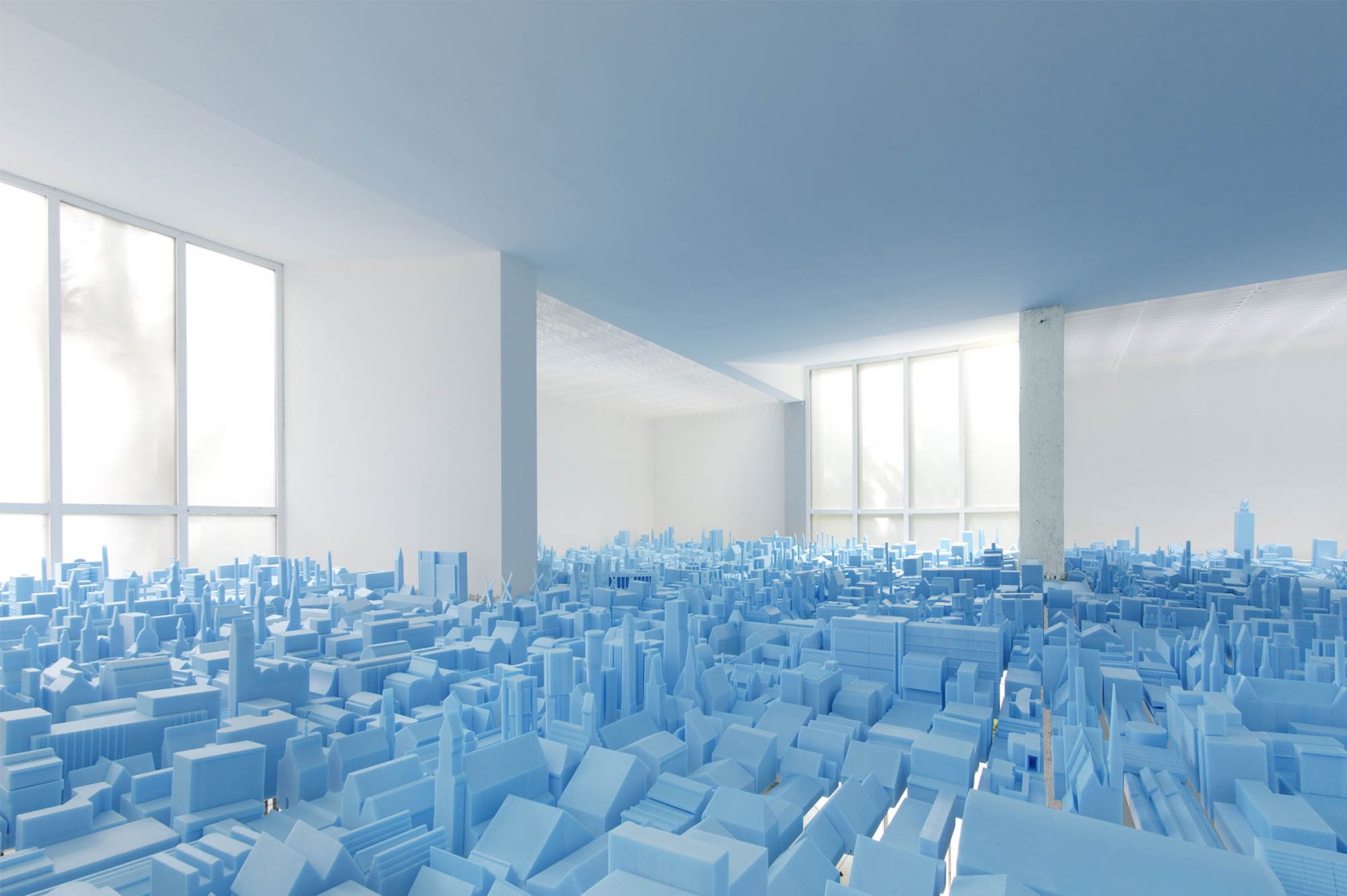

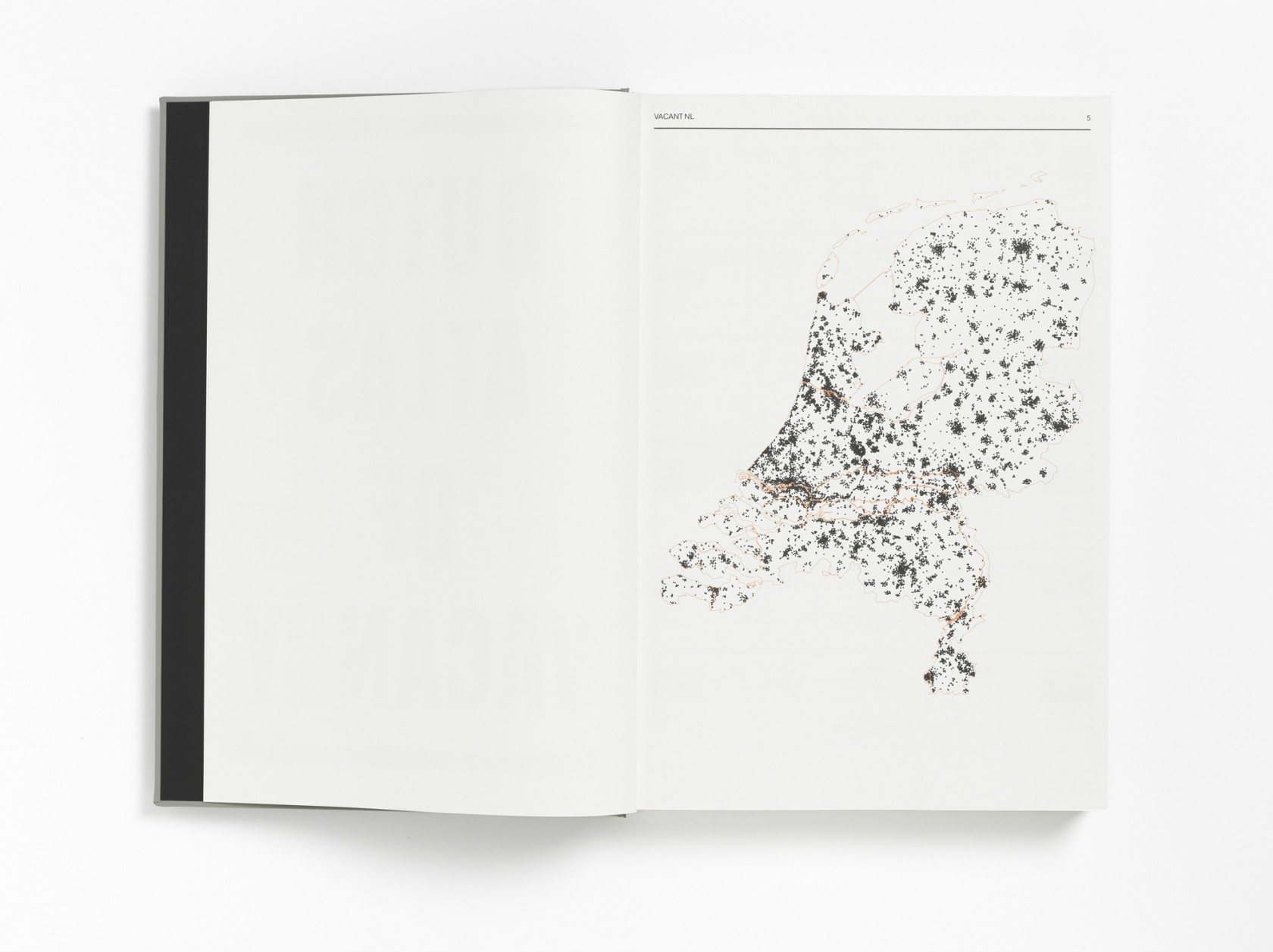

RAAAF are renowned for a number of projects. In 2010, they curated the Dutch pavilion at the Venice Biennale, showing a ‘sea of vacancy’ in their Vacant NL exhibition, consisting of models of the 10,000 vacant public and governmental buildings in the Netherlands which visualised the potential for reuse, experimentation and innovation. The exhibition put vacancy on the map and made the reuse of vacant buildings one of the Dutch government’s main planning priorities. Nevertheless, RAAAF argues there is still a long way to go in applying innovative design and regulatory strategies to vacancy, in order to turn spatial and economic failure into fruitful grounds for new activity.

Another central theme in RAAAF’s work is ‘affordances’, the possibilities for action provided to us by our environments. This relates to the long term research project by philosopher Erik Rietveld at the University of Amsterdam. In the book it is explained that the wide variety of vacant typologies offers endless possibilities for types of (re)use, not only because of their physical qualities, but also for their social, economic and institutional embeddedness – the possibilities to link the use of space to knowledge networks, social fabrics, services and business activity. This means that standard design and project development methods are not enough for exploiting the full potential of vacancy. Education also plays an important role here, as traditional design training is insufficient to deal with current spatial and societal challenges. Last year RAAAF led the Master’s programme Vacant NL at the Sandberg Institute.

RAAAF argues that governments should encourage the agenda by allowing temporary use in governmental and public buildings. This makes sense, otherwise they consist of idle public investments that do not contribute to urban dynamics. In the Dutch case, these thousands of buildings include palaces, prisons, churches, convents, water towers, lighthouses, fortresses, bunkers and office buildings stemming from the 17th to the 21st century. Especially for the older structures, it is interesting to think about temporary use in relation to heritage and preservation. Perhaps there are alternatives to conservative heritage approaches and ‘museumization’, which often do not capture the ever present heterogeneity of narratives. These notions could be confronted with contemporary reappropriations and new histories, by creating an active relationship between them and their users that is unscripted and ‘truly authentic’.

The change RAAAF envisions in education entails that alternative approaches should be taught, and that design education should also include political science, public space theory, economics, philosophy, visual arts and interaction design as vacancy is a complex phenomenon that is linked to many professions and societal dynamics. Realities in which designers have to operate have changed, with different relationships between the designer and the end user, as well as the relationship between thought processes and realization.

The book explains how the students in the Master’s studio Vacant NL were trained for two years to acquire the skills to design for temporary use, and what the tutors themselves learned from the education process since this is a new way of training designers. Different approaches to vacancy by the students (from alternative ownership and lease models to artistic interventions) are described in the book. The lecturers state “it is important that this discipline reaches adulthood in the coming years without losing its playful and flexible nature”.

The work of RAAAF on the crossroads of architecture, art and science is diverse, but mostly builds upon vacancy, temporariness and unorthodox use. Their ‘Dutch Atlas of Vacancy’ which accompanied the 2010 Venice exhibition is an inspiring call for action. Bunker 599 is a poetic intervention in an idle bunker which, paradoxically, became a national monument after RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon sliced it in two. Secret Operation 610, another art project which they did together with Studio Frank Havermans, is a remote-controlled Star Wars-like structure and a playful boy toyish intervention created in a vacant hangar at former Soesterberg Military Airbase, now functioning as a meeting and working space for researchers. RAAAF explains that these art commissions are extremely valuable to them (compared to more rigid architecture commissions), since they allow for more space to realise RAAAF’s ideas encompassing architecture, art and science.

Contextualising changing realities which require alternative approaches to spatial use and design, highlighting innovative approaches and showcasing RAAAF’s own work, the book takes a broad perspective on temporary use which makes it accessible to a wide audience.

The term ‘sequential temporariness’ is dropped various times in the book as an important thing, which implies that a clear time span and a following move are healthy. If a space is available for a limited time, this very fact makes people design, build, invest and work differently. This understanding embraces and seeks to stimulate the constant and desired dynamic nature of the city.

A tiny concern is persistent in the back of my head: new dynamics and energy in a city are applaudable, but temporary use has consequences. It can also work as fertiliser for processes of upgrading and gentrification, which can have negative effects for the city including displacement and monocultural environments. Temporary use can be cynically used by governments or developers to add ‘coolness’ to a place in order to increase its investment potential and hide market failure: buzz disguises decline. Nevertheless, if initiators and designers are aware of this, they can apply conscious strategies that neutralise these effects to a certain extent by, for example, making their projects as inclusive as possible and creating impacts that do not only affect property values.

The main message of the book is a clear one: vacancy isn’t only a problem. It offers potential for innovation on different levels – from use, design, ownership, collaboration and thought to investment and institutional configurations. The publication looks at the temporary beyond the pop-up shop and the aesthetics of recycled pallet wood, and sets the agenda for new approaches to vacancy, collaborative innovation, fresh institutional attitudes and alternative design education.

The cover photo of this article is taken by John Phillips.