The Dutch pavilion at the 2014 Venice Biennale celebrated the architect Jaap Bakema and his visions of the open society. One of his designs is the former printing presses of Trouw, a prominent Dutch Newspaper. The building was later converted into a club, cultural venue and restaurant: TrouwAmsterdam. By looking at the the use and meaning of the building during that period, we reflect on Bakema’s notion of openness. The media we used were all found online, ‘out in the open’.

Welcome to Trouw

Cross Amsterdam’s inner ring road, which separates the seventeenth century canal district from the rest of the city, and cycle five minutes in an eastward direction to reach TrouwAmsterdam. The club, restaurant, and cultural venue occupy the front part of a vast concrete complex. The building’s long black façade is a visual void and is easily overlooked, so look for the word ‘Trouw’ written in illuminated orange colored letters.

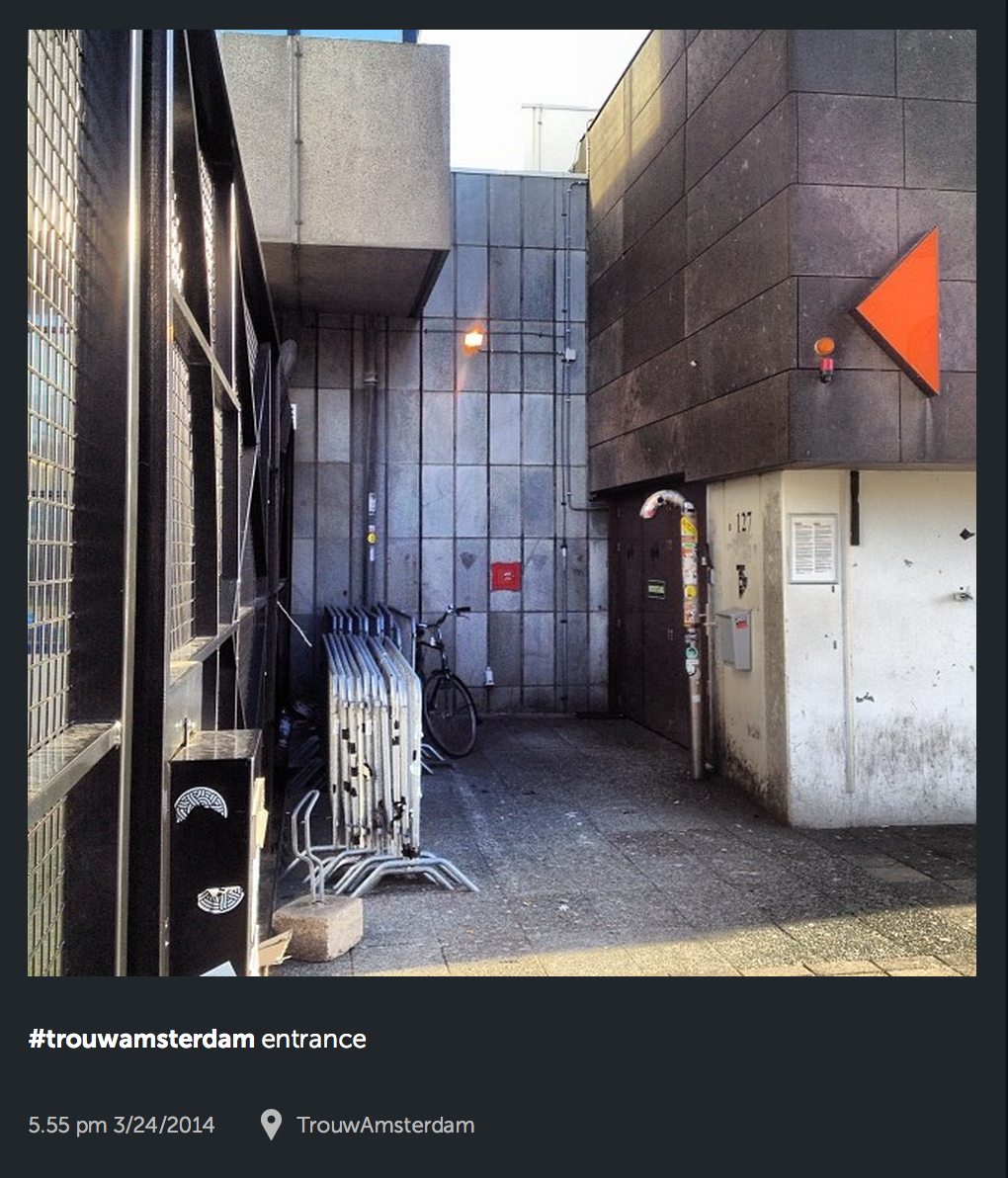

Park your bike and cross the square. In front of you is a black fence, preventing you from accessing a dreadful display of architectural disdain and urban decay. Devoid of signs of life or color, the half-enclosed space echoes scenes from La Haine, Control and other dystopian black-and-white films set in hostile urban environments. Turn right and you’re welcomed by a maze of metal crush barriers and a handful of bouncers.

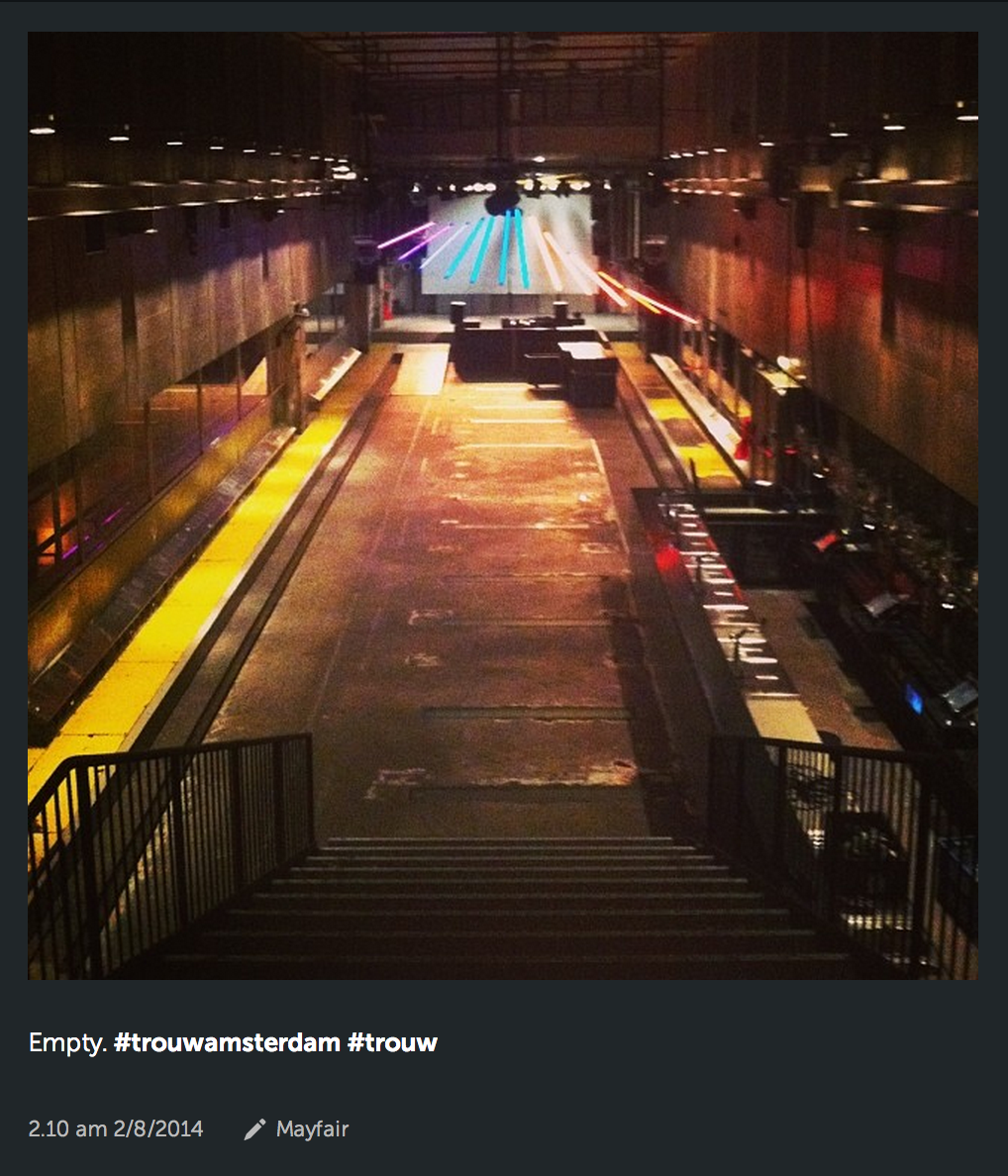

Skip the queue by pretending you’re on the VIP-list. Once you’re in, stay cool and tell the cashier you forgot your all-access Trouw ring. Climb down the stairs into the basement of the building. You are entering a machine. Pipes and ducts for heating and ventilation crisscross the ceiling. Iron tracks that were used to move massive paper rolls around the building, are embedded in the floor. Eye washers hang from the walls, revealing the toxic nature of the newspaper production that happened here, adding drama to this subterrenean nightlife bonanza.

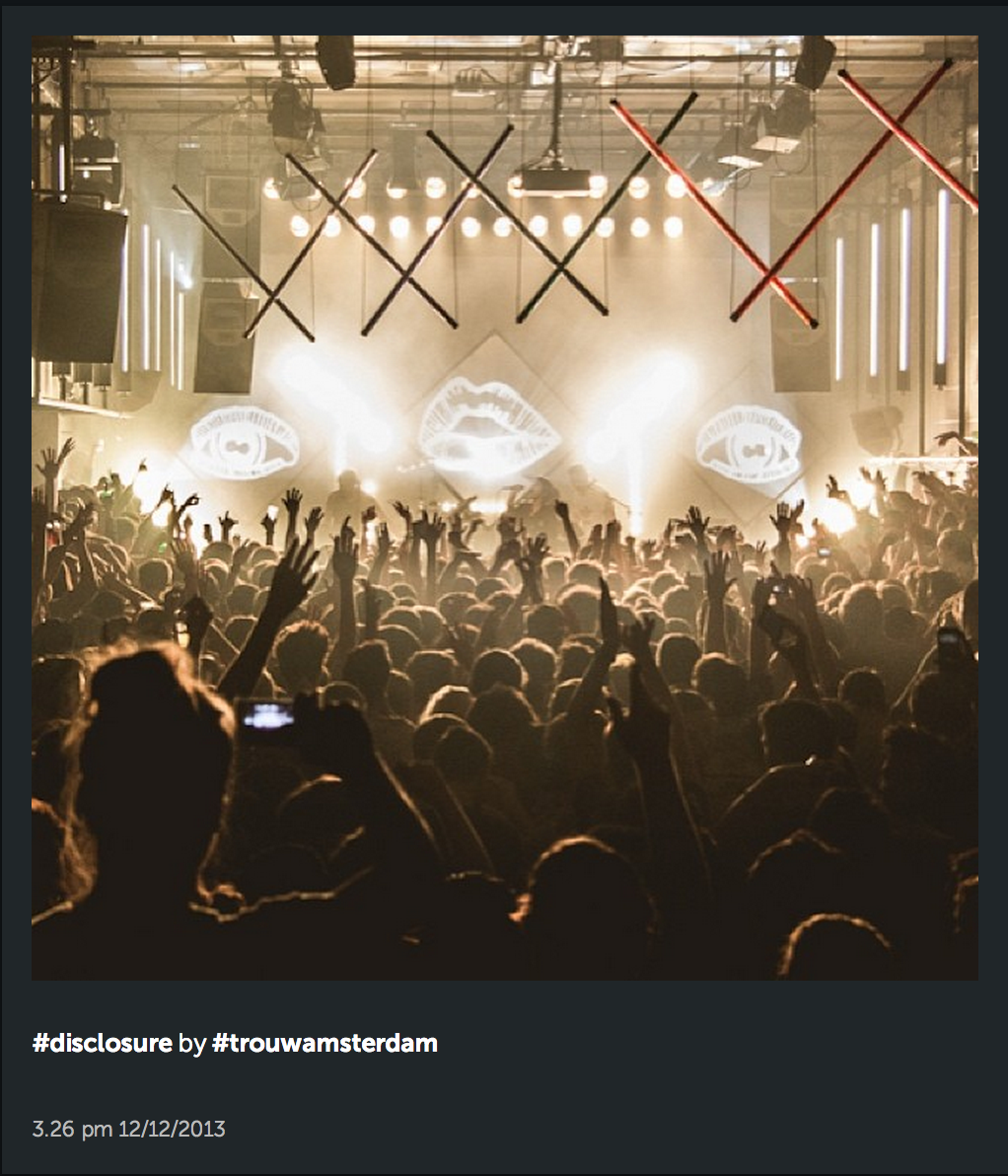

The intense sound of sub bass frequencies and cheering crowds drowns out any conversation, your phone has no service, people around you are high. Go up and keep on moving until you hit a barrage of sound waves coming from the wall of speakers in the main hall. Immerse yourself, take a deep breath, let go of your surroundings and find your essence without context. Forget that everything will be over soon, that the club and the crowd will soon be replaced by a new hotel and corporate business-types.

Waiting for Wibaut

The low-rise Trouw Building is an architectural anomaly. Its industrial rawness stands out in a city known for its sophisticated residential architecture. The austere precast paneled building stands in striking contrast to the lusciously decorated and handcrafted houses a stone’s throw away along the Amstel River. Together with the neighboring Parool Tower it was designed by Van den Broek en Bakema in the late 60s to house the editorial offices of some of the country’s most important newspapers. In a soundproof extension that was later added, printing presses were spitting out the daily news for several decades until the newspapers moved their operations elsewhere, leaving behind a cluster of empty buildings.

Big-lit letters still adorn the facade of the Trouw Building and Parool Tower. Originally planned for a location in the old city center, increased car mobility and an appetite for Modern aesthetics made both newspapers decide to take their ambitious plans beyond the inner ring road and create Amsterdam’s own ‘newspaper row’.

The two buildings sit at the heart of the so-called ‘Parool Triangle’, a three-cornered area along the Wibautstraat. It is the only road link between Amsterdam’s outer ring road and the city center and was named after the prewar Alderman of Public Housing – and working man’s hero – Floor Wibaut. Envisioned in the 1930s as a splendid avenue to rival the Champs Élysées in Paris or Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm, the street never lived up to expectations.

Alongside the four-lane thoroughfare emerged a remarkable hodgepodge of architecture, from truly majestic to plain miserable. The street has created a heavily trafficked no man’s land, disconnecting Amsterdam neighborhoods from each other and creating a barrier between the prosperous Amstel River waterfront and run-down areas to the east. Local residents avoid it and companies have slowly abandoned it; only commuters temporarily fill the space, zipping past by car or subway.

For a long time nothing happened, no politician could ignite the long awaited regeneration of the street. But in the last five years, thanks to pioneering entrepreneurs and partying Millennials, the situation has turned around.

Crash, Crisis, Trouw

When the credit crisis hit in 2008, causing most real estate developments to abruptly stop, a group of young entrepreneurs decided to defy the odds and move into the abandoned Trouw Building. Slated for demolition to make way for luxury condominiums, instead the building became a temporary lifestyle hub. With minimal means and with joint forces the initiators managed to convert the bare concrete spaces, built to withstand the weight and noise of rattling printing presses and spinning paper rolls, into a habitable place.

TrouwAmsterdam was founded by a group of DJs, restaurateurs, festival organizers and friends, all in their 30s. They titled their business plan ‘Crash, crisis, Trouw’. As soon as they received the key, they opened up the building and started organising informal parties and exhibitions amidsts the debris of the dismantled printing plant.

Only a month after they started, the New York Times called them ‘an emerging center of hip’ and quoted one of the founders saying that “We like to sort of hint at the history of the building. We just put in a kitchen, a sound system and a bar. We haven’t even cleaned up any of the ink stains”. Over time the building was further humanized with hand-printed signage and site-specific graffiti. Holes were drilled into the thick concrete floors to facilitate the flow of people. To improve the building’s accessibilty, a red-colored entrance was added, splitting open the monolothic façade like an abdominal incision. The key characteristics of the building were cleverly re-used to fit the ambitions of the new program. As it turns out, the building’s machine acoustics are perfect for music productions, the lack of daylight creates the surroundings for an intimate experience, and the vast concrete surfaces serve as projection screens and canvases for the display of art.

Modeled after the idea of a ‘city in the city’, with a population of up to 2,000 people during the weekend, visitors can literally spend the entire day and night roaming through the succession of rooms to eat, dance, enjoy art, bowl, and make love. And by keeping the name, which translates to ‘faithful’, Trouw created a trustworthy brand that echoed the revolutionary history of the eponymous newspaper that was founded during World War Two in resistance to the Nazi occupation.

Hipsters in Alphaville

Trouw has succeeded in creating a mix of aesthetics that suits the contemporary cosmopolitan youth, who cross the globe like a herd. This brought Trouw to the top of the list of places to visit, but over time also erased its subversive character. Trouw’s look and feel evolved over its life span. The structure looks authentic and rough, but has been cleverly reappropriated with fake oil stains and a 60s typeface.

Concessions were made to the initial raw minimalism of cold concrete chiq by adding wood touches, plants and nostalgic furniture in order to adapt to contemporary tastes, giving in to the ironic consumption of the hipster who longs for an idealized and personalised past. Trouw blends 60s architectural minimalism and revolutionary attitudes with 70s hippie notes of nature and humanism, 80s post-industrial punk and Detroit warehouse aesthetics, and a 90s air of improvidence. Trouw occupied an architecture with dystopian connotations and made it suit contemporary edgy tastes, while simultaneously contributing to the local appreciation of Brutalist architecture.

But all that is solid melts into air: temporality is key for contemporary party robots because what’s leading edge today is conventional tomorrow, forcing the fluid herd of hipness to move on to the next pristine place in an infinite lifestyle-loop.

Pebble in the Pond

Trouw’s distinct image has put itself and Wibautstraat on the map for people from Amsterdam and beyond. Together with another cultural venue opening up in the former modernist headquarters of newspaper Volkskrant just across the street, they were the first trailblazers to set up shop in the area. The housing corporation that owned much property in the area actively approached the initiators of Trouw to begin business there, while the municipality gladly supported the process.

Often voted as the ugliest street in Amsterdam, Wibautstraat has now become one of the city’s new frontiers for people to visit and investments to land. Trouw paved the way for young urban consumers into poor, underdeveloped territories – which are still close enough to more affluent parts – and intensified gentrification in the neighboring area. An upmarket pop-up restaurant opened up next door, new apartments are being built along the street and the former Volkskrant headquarters-turned-art-incubator has been redeveloped into a creative hotel.

By creating new demands TrouwAmsterdam opened up formerly unwanted parts of the city, but also attracted investors to its own structure – the now-iconic building will no longer be demolished – ultimately pushing out the Trouw team and their visitors. Towards the end of 2014 the people running Trouw will end the club and move on.

In Trouw we Trust

A while ago, Trouw started handing out a limited number of gilded and engraved rings to its most appreciated guests – rings that connect people to Trouw wherever they go, that include them in the Trouw community and that give them premium access to events. It opened up the premises to faithful fans, leaving others in lengthy queues. But it’s not only the Trouw ring that binds its wearers to Bakema’s building, every utterance of Trouw’s public relation department aims to do the same. Through social media outlets it constantly creates and reproduces a stable image of an edgy, Berlin-like hotspot, making people trust Trouw for its ability to transform themselves after its image.

By doing so, Trouw offers a sense of belonging to those that lost their faith in traditional institutions or online networks and look for more intimate, tangible communities. Trouw provides them with an adventurous relationship, while being aware it will ‘quit’ as soon as it has to leave. At the same time, Trouw’s public isn’t a faithful lot either. They might carry their Trouw ring around the city, but when another place suddenly becomes more attractive, they might cheat as well. Trouw understands that this kind of relationship might end as easily as a modern marriage: for instance at a special event called the Ontrouw-night people are actually prompted to be unfaithful.

Careless Dystopianism

Trouw’s young, tech-savvy crowd loves social media. Every event in Trouw is documented on Twitter and Instagram to such an extent that the building has as much of an online presence as offline. The accumulated layers and constellations of data rip the building apart, its weathered concrete now floating in the cloud in thousands of JPEG-images. The real life perceptions and emotions can be experienced in any given location in the world and stored for eternity.

The tweets, tumblrs and flickrs of that specific summer night will tell its course of events for the years to come, all details accessible by anyone at anytime. While it’s obviously good free advertisement, Trouw attempts to control this leaking of data. By asking visitors to cover up cameras – no photos, enjoy the moment! – it creates a false sense of privacy and togetherness. Although the flow of pictures seems now contained, smartphones and apps still relay critical amounts of information. The state and telecom providers – and who else? – know where you are, at what time, and with whom. The loyal crowd doesn’t care about uncontrolled surveillance and continues to party like it’s 1999.

Memories of the Future

By smartly recycling appealing re-interprations of past decades – 60s revolutionary spirit, 70s hippie-culture, 80s underground resistance and 90s hedonism – Trouw itself is now perceived as contemporary cool. During its own lifetime, it went from forward-looking to nostalgically inviting Ostgut Ton (the label owned by Berlin’s famous Berghain club, which is explicitly refered to as an inspiration for Trouw). Initially unable to fill up the rooms, there are now 600 people queuing outside its entrance. Obscure popcultural events were transformed into massive club nights.

Trouw ‘normalized’ the aesthetic of ‘trashy chic’ in Amsterdam and by doing so, it commodified itself and the building. It became fertile ground for new investments. The big money will likely materialize into yet another hotel, with Trouw’s initiators moving on to another vacant building and its footloose visitors left to float around the city in search of a new hangout. But then again, as Bakema already prophesized “it’s the task of each generation to overcome the past and to seek new concepts of form”.

Failed Architecture was invited to write this article by Het Nieuwe Instituut. It first appeared in the catalogue of the Dutch contribution to the Venice Biennale 2014, which was produced by Volume. The catalogue is included in the latest issue of Volume: ‘How to Build a Nation‘. TrouwAmsterdam went out with a bang on December 31, 2014. The building’s next life: a Student Hotel.