As Istanbul undergoes a process of “Urban Transformation,” the plight of dispossessed residents and the bulldozing of historic UNESCO sites are apparently small trivialities. Human rights, historic preservation and even ecological sustainability are strange, unquantifiable concepts compared to the fruits of economic growth. So let us forget these elitist European ideals for a moment, and discuss the economic cost of urban transformation through the lens of an Asian urban concept: Metabolism.

While the Japanese Metabolists’ design work of the 1960’s failed to offer the rapid flexibility it promised, it still serves as an analogy for an adaptable urban form. Istanbul’s historic pattern of differentiated land ownership has been the DNA behind its adaptability, the crucial attribute needed for survival. A shish kebab of various programs, architectural styles and building heights skewered to the street, this dense and pixellated urban form can easily absorb shifts in the economy. But the current process of urban transformation consolidates these cells into monopolies. Like dinosaurs, they are large, slow beasts, unable to evolve under a changing environment.

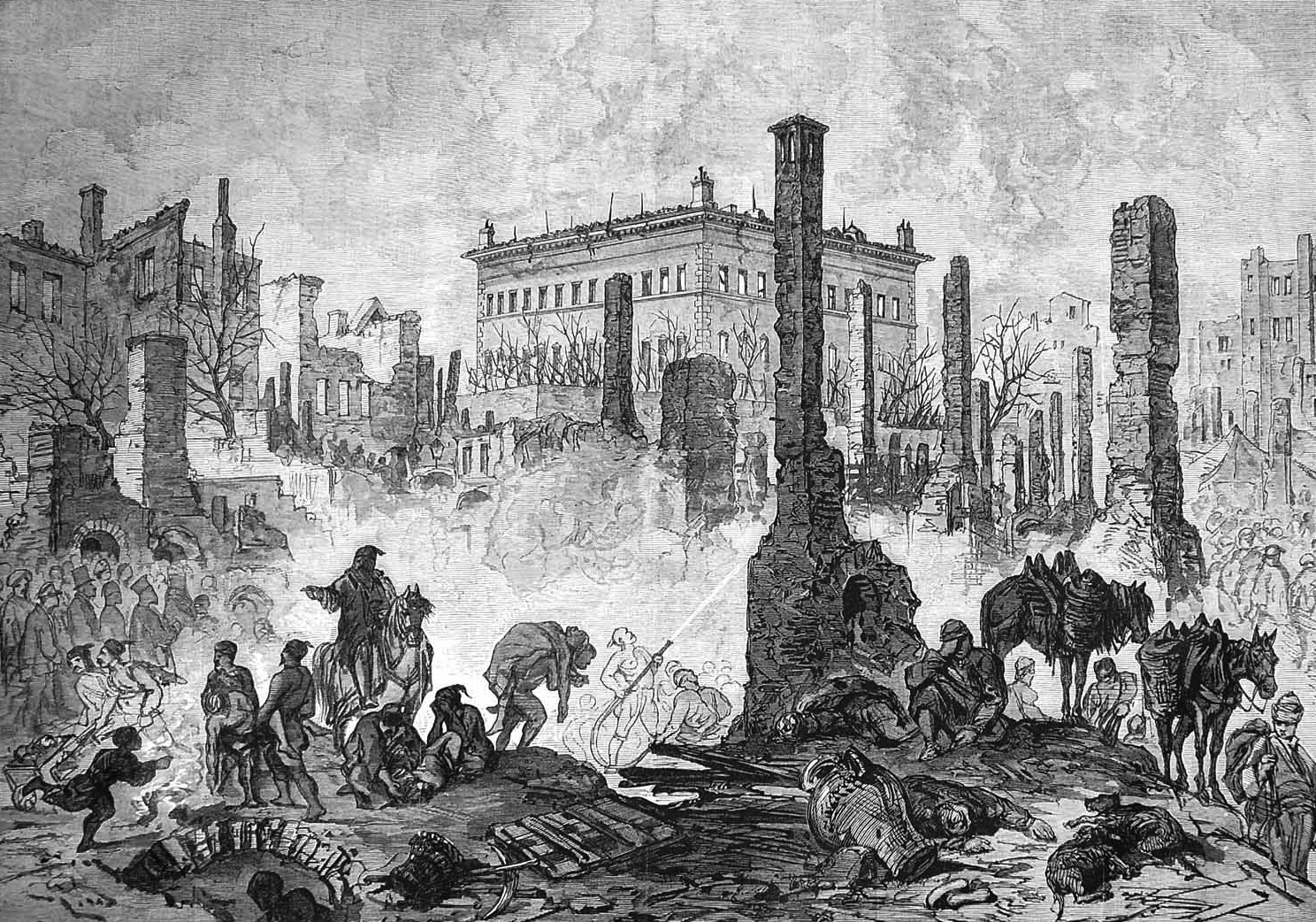

Fires and Parceling

In fact, Istanbul already went through a period of urban transformation. Massive fires consumed most of the timber-built Istanbul in the 19th century, opening up land for modernization. During the period of Tanzimât reformation in the Ottoman Empire, the Grand Vizier Mustafa Reşid Paşa hired European urban planners to redevelop the scorched land of the medieval metropolis by “tracing the streets according to geometric rules, by leveling certain places as much as possible, and by building masonry houses and shops in a new style and attractive form.” Reşid Paşa, a former ambassador to France and the UK, also adopted the English row-house as a model for Istanbul: the single family walk-up was seen as an autonomous unit fitting for the predominantly Muslim city.

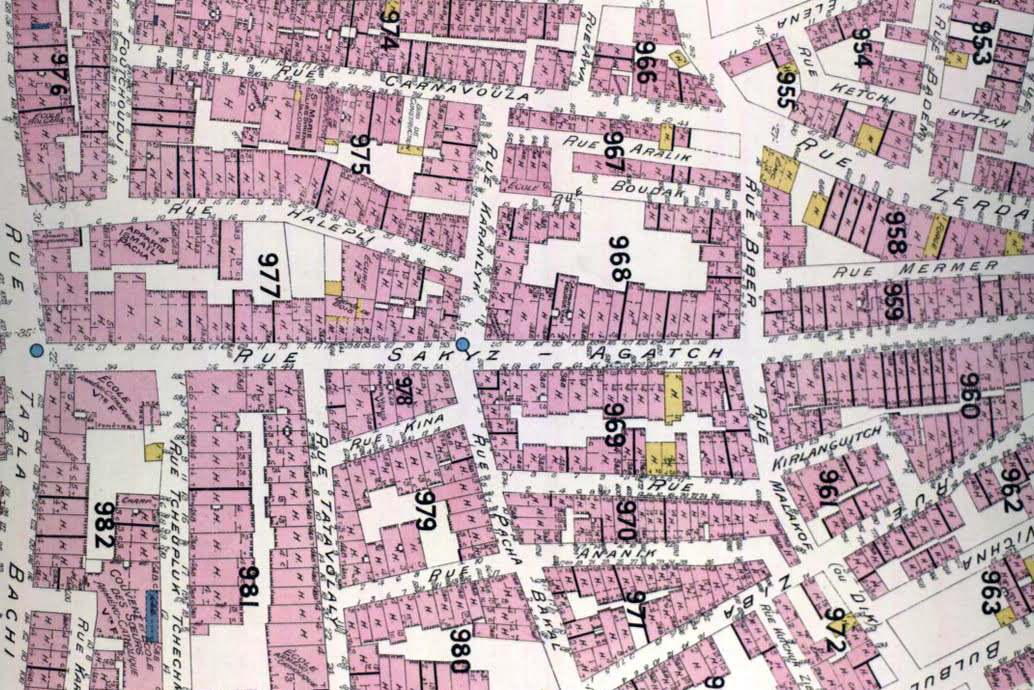

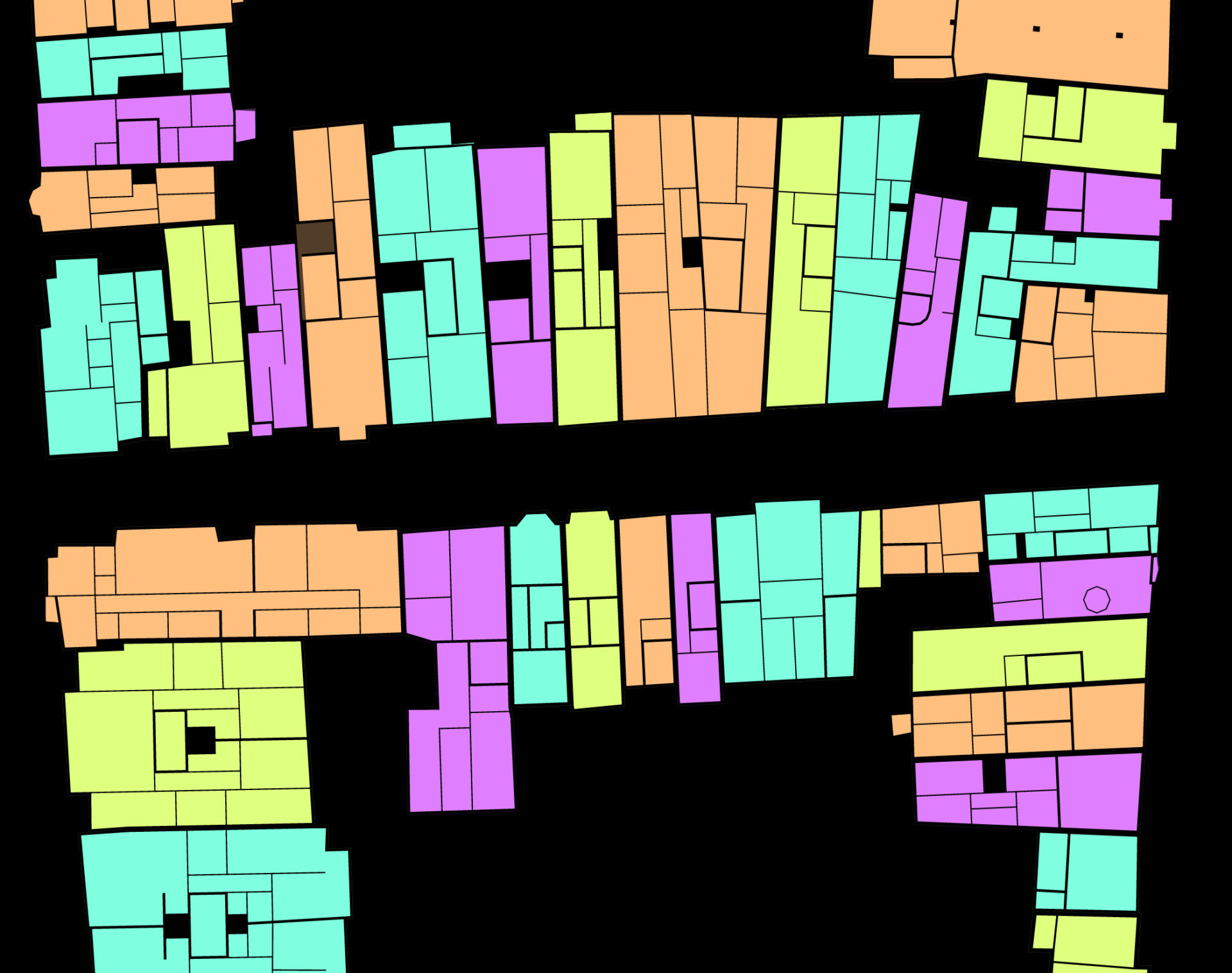

But while London’s estate parceling resulted in controlled, repetitive houses organized around central gardens, Istanbul’s post-fire parceling was highly idiosyncratic. New street grids had to deviate with respect to extreme topography and important masonry structures that survived the fires, such as mosques and churches. Planners also struggled to graft their rational grids into surrounding neighborhoods. And in fact plot divisions were never actually drawn: the original residents were to be given parcels of land proportional in size to their original, but continuous disputes were never resolved until the buildings were built. Lacking uniformity, these parcels were the foundation for a highly heterogenous pattern of urban development.

Having lost surface area to make wider roads and avenues, these new plots were given minimal street frontage and were of narrow, deep proportion (usually four to six meters wide, 10 to 30 meters deep.) Changing hands over the last 150 years, these tiny slivers of land have remained the constant as Istanbul has evolved. Adding floors, cantilevering over the streets with cumba bay windows, or even redeveloping the land, buildings often remain just one room wide. A City of Rooms, Istanbul is composed of the most basic of building blocks.

Mass Housing: Big, Slow, and Stupid

Fires created the incentive for Istanbul’s urban form, but another disaster threatens it. Across Istanbul, whole neighborhoods are being demolished because of a perceived earthquake risk that unsound structures pose. In one case, an entire district of 5,560 houses was deemed “at risk” based on the visual analysis of just 14 buildings. It is often expressed as a formalizationof gecekondu, “built overnight” informal slums, yet much of this restructuring is occurring in areas already formalized in the 19th century.

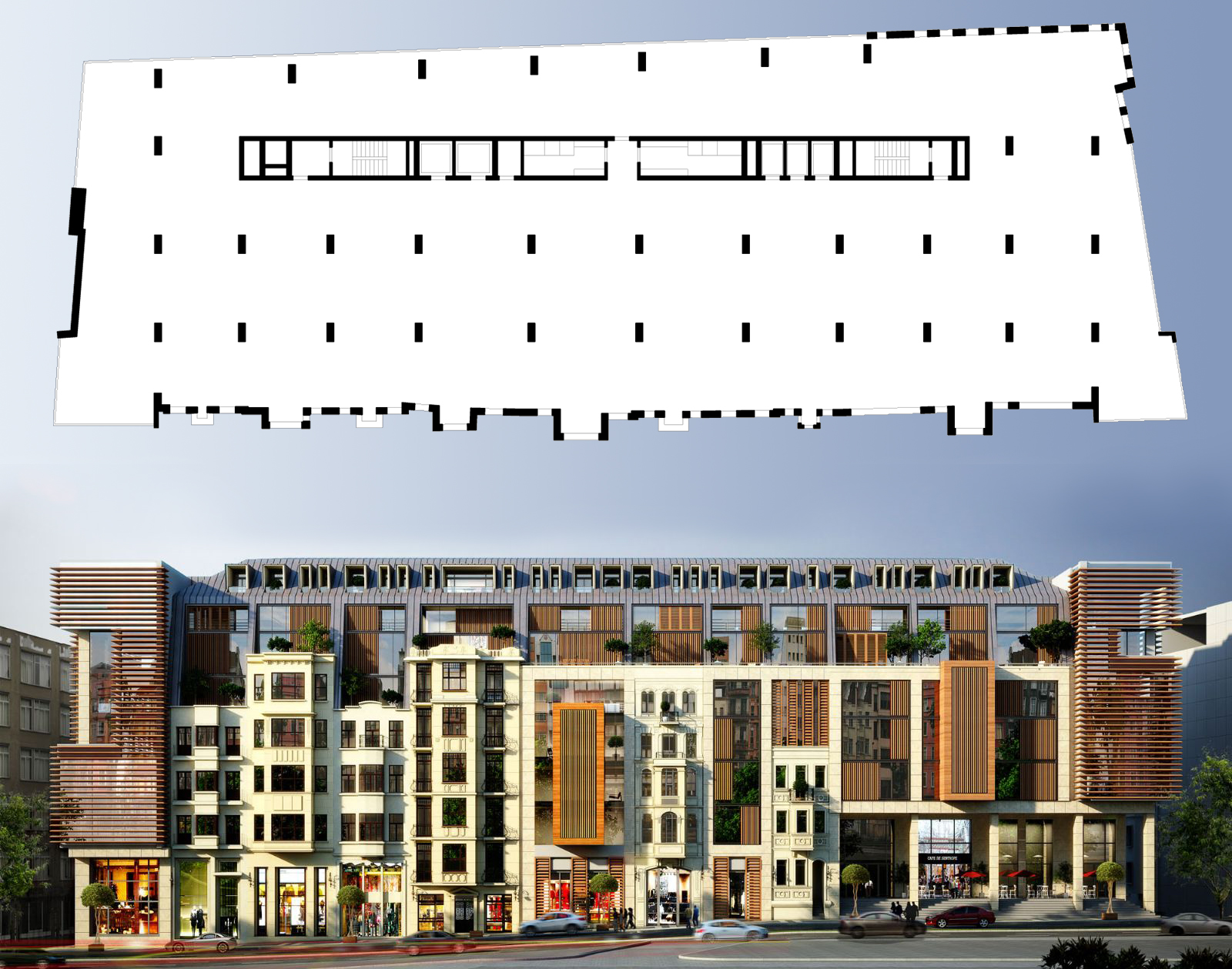

In Fikirtepe, on the city’s Asian side, 4,500 individually owned parcels have been consolidated into 57 mega-blocks; thousands of houses razed to make way for housing towers and shopping malls. Hastily pushed through permitting without adhering to any urban principles, these projects could actually be considered less formal than the fairly regular pattern of houses that preceded it. Projects are still “built overnight,” the only difference is scale.

This lucrative business of redevelopment has dire consequences on the city’s growth. The old patterns of differentiated land ownership allowed for residents to expand vertically, even to 10 stories in some neighborhoods. This vertical growth offered a method of capital gain to residents who could rent out extra floors, a profitability not possible when you only own an apartment in a highrise. Likewise, vertical growth absorbed population increases as Istanbul became more dense; without it the city can only sprawl, leading to higher costs for infrastructure.

In their seminal Behaviorology book, Atelier Bow-Wow compare the Metabolists to the reality of Tokyo: while the avant garde architects of the 1960’s imagined flexibility structured around vertical cores and bridges, Tokyo’s intense metabolism is actually determined by privately owned properties that regenerate themselves. In this Lockean view of possessive individualism, the initiatives of individual families are far more responsive and productive than concentrations of power and capital.

The same intelligence is embedded in Istanbul as well, where owners of small properties have the agency to quickly respond to changing economic demands: converting them into apartments, offices, hotels, or even small-scale factories and workshops. This agility is lost in a highrise: fixed infrastructures, regulations, and plan morphologies keep such developments from becoming mixed-use environments. Metabolism is also concerned with cycles of preservation as well. One only needs to be reminded of the disaster of Pruitt-Igoe to understand the problems of maintenance in big, complex and bureaucratic structures.

Hundreds of thousands of apartments are being built in Istanbul with the same floor plan. A very small group of developers deciding Istanbul’s housing market have approved a very small collection of acceptable flat types. But in both nature and in the stock market, diversification is key. While the heterogenous buildings in Istanbul’s older neighbourhoods produce a variety of options, what will be the value of a standard flat in oversupply?

In Tarlabaşı, a neighborhood in central Istanbul near Taksim Square, another urban transformation project wears a mask of urban vitality while eating out its heart. The 9-block redevelopment, financed by private developers with the municipal muscle of eminent domain, preserves the characteristically narrow, historic street facades. Yet behind this pleasant collage of masonry houses, mammoth floor slabs are being poured. A neighborhood that has undergone many gradual transformations with changing occupancy in the 20th century, Tarlabaşı will be effectively paralyzed, its syncopated skyline frozen in time.

In a recent article, Amale Andraos discusses the crisis “big” architecture faces as it usurps urbanism. Although formally complex, these XL-scaled projects fail to appropriate the city’s “more productive aspects, such as the embrace of density, compression, intelligent and shared infrastructures, and a more careful integration of landscape and ecological systems.” The heroic modern period celebrated mass-production for its speed, yet its legacy has ironically slowed down agile urban economies. It is only when we consider the individual as having agency within the city, that a “smart city” can be as intelligent as the people living in it.