For many coming to New York City, the available entry is the Port Authority Bus Terminal (PABT). However, if a traveler seeks the charm of a grand entrance, they will be greatly disappointed. The PABT is considered, colloquially, to be a hall of unfathomable nightmares. As one Yelp! reviewer put it:

“If I die and go to hell, I think it might resemble this.”

With another cryptically writing:

“Nothing makes sense. I will never be the same.”

Despite this general, frothy disdain there is no suggestion of tearing it down. In fact as of Summer 2014, it is slated approximately $90 million for improvement renovations. How then did a place so hated even come to be? The answer is a tale of necessity, ego and intention gone horribly awry.

A Dark and Stormy Night

In 1921 New York City had a problem (one of many): Hundreds of buses were navigating to different drop-off locations, causing commuter havoc. It was through this storm a cross-state agency called “The Port Authority” was formed.

23 years later (under the leadership of Frank Ferguson) the Port Authority announced their intent of creating “The World’s Largest Bus Terminal”. A project to be funded, designed, constructed and operated by the agency itself. No specific architect was highlighted in this planning, leading several to believe the structure would be designed by committee. It almost certainly was. However it would not be until 1946, that the stars would be aligned for construction. The delay came down to the famous and infamous commissioner, Robert Moses.

Moses had developed a deep hatred towards public transportation and made it his mission to eliminate it. Without a charismatic figure to oppose him, it seemed the Commissioner had no obstacle. Allied with the Greyhound Bus Company, he mounted a two-year counterattack against the proposed terminal but was eventually beaten. The PABT construction had been a rare defeat for Moses, but he was not done fighting.

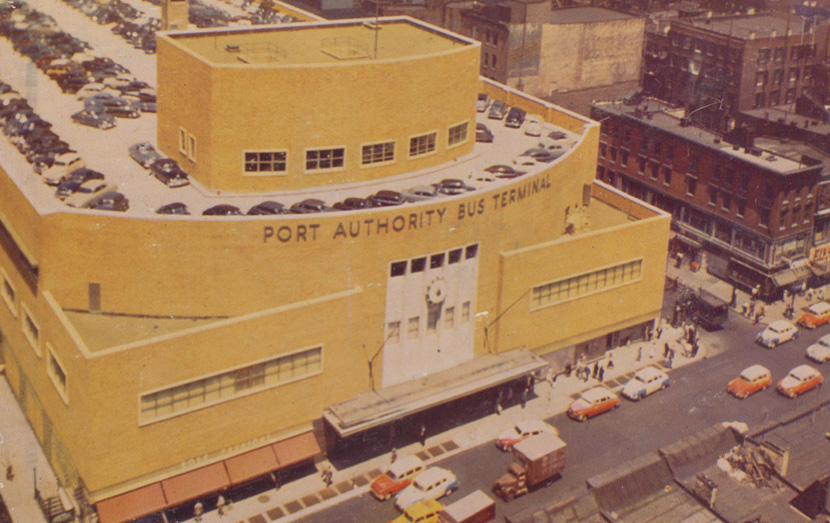

Originally built as an art-deco influenced structure with the parking lot on the roof, the building was relatively well received. Taking up roughly the size of a city block, the warm brick colors were very much of the Works Progress era. Clean with an almost moral simplicity. It was completed in 1950, as advertised, for the price tag of $24 million.

Yet even at its opening the facilities were not enough and the agency sought $550 million for continued renovations over the next ten years. Moses however, had other plans. As the de facto Tsar of New York’s urban planning he used all of his acumen and ability to encourage individual vehicle agendas. By 1955, he had influenced planning so much that almost all transport funding was promised to highways and parking. Sure enough, the PABT fell into disrepair.

Mad Men

Unsurprisingly 1960 brought the PABT’s first large-scale addition: a three floor parking garage. Formed mostly of steel and not reflecting the original design intent, it was a grim portent of things to come. By 1966 the building was already overcrowded and garnering a terrible reputation. The renovations were haphazard, quickly done and lead to lingering user confusion. With millions of day-to-day transitory passengers, the terminal was also becoming an epicenter of crime.

On the other side of town, Moses was losing the popularity that had been so crucial to his political strength. In the end what brought him down was a literary one-two punch. The first book was 1961’s The Life and Death of Great American Cities, where dark horse Jane Jacobs systematically broke down each of Moses’ efforts as short-sighted at best and bigoted at worst. The death knell for his career was 1974’s The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro which portrayed him as a complex, but ultimately extremely flawed planner. Though he was out of the picture, his prejudice against the PABT had already had its effect.

By the 1970s New York had a distinctly different reputation than it had only 10 years before. The economic troubles facing the United States seemed to be condensed into the city itself. It was no longer the New York of Broadway babies and glimmering optimism, it was instead the setting for the Son of Sam murders, rolling blackouts and massive unemployment. The PABT subsequently became a nexus of social issues, from prostitution to panhandling. In 1977 a user survey was commissioned to see what patrons thought of their experience at the terminal. The findings were not glowing to say the least.

In the wake of these problems, the building again went under renovations. The 1979 Port Authority designers expanded the building another 50%, covering up the bricks with darkly painted exposed metal beams to match the 1960 garage aesthetic. This renovation made the natural light, if indeed there had been much to begin with, almost indistinguishable from the fluorescent tubes. The final floorspace toppled over 1.5 million square feet.

Though afterwards the PABT was all but ignored. The booming Reaganite economy of the 1980s meant travelers could do better than the bus and focus was placed on Airports instead. While the usage of the Bus Terminal did not lighten up, the pressure to make it a usable space dwindled. Moreover, the expansive parking garages, which had at one time been packed, were now sparsely used. Resulting in underlit and underutilised space that was notorious for both prostitution and rape. Additionally the elimination of nearby federal mental-health facilities meant the city’s homeless settled in, finding the PABT a better option that freezing to death in harsh New York winters.

Give’em The Old Razzle-Dazzle

Ten years later, the adjacent theater district revival put pressure on the PABT to clean up its act. The Port Authority hired the still-in operation nonprofit, Project for Public Spaces (PPS) as a consultant. PPS submitted about 100 suggestions for improvement, and hoping to make them a reality, the Comprehensive Improvement Program (CIP) was established in 1992. Some of the suggestions included improving entrances, streamlining circulation, straightening site lines and, of course, alleviating the homelessness problem.

A positive spin on the initiative that followed would classify it as ‘directing the homeless to facilities elsewhere’. An alternative claim was the homeless were being ejected to certain peril. To address this concern, the Port Authority staff were encouraged to identify the differences between loiterers, vagrants, and ‘street people’. The subsequent effort, known as ‘Operation Alternative’ meant that suggestions could be offered for charitable gathering space, rather than physical removal. At the end of the day, there was not much that could be done for the issue aside from best-judgement and individual circumstance on the part of the Port Authority staff.

For a while, Operation Alternative and the design suggestions seemed to work. Customer service was at an all-time high and while the building still had serious architectural and space-planning issues that could not be easily resolved, there was marked improvement.

Then the recession hit.

The Who-Dun-It

If the question of the PABT’s terribleness was a true crime novel, the guilty party is everyone involved. That’s right: they all did it. The original Port Authority designers did not anticipate long-term requirements. Robert Moses did his best to destroy it. The economic downturn of the 1970s made crime rampant. The 80s boom ignored social problems. And now, the impossible maintenance costs of a 1.5 million square foot structure with a bad reputation burdens everyone.

The Port Authority Bus Terminal proves that modern monsters are complicated creatures, only as ugly as their resonance is. This next chapter could finally be the one that turns it around, but then again it might be just a $90 million plaster on an infected wound. Either way the sordid past of the PABT is no easy shadow to escape. Especially when the Chinatown Bus is only 10$.