Rose Revolution Square in Tbilisi was once called Republic Square and has been showcase of different regimes, conflicts and aspirations. Despite being one of the few squares in the city, it keeps transforming, heavily influenced by different powers ruling the country. A closer look at its history and current condition may reveal what Tbilisi’s downtown will actually become: an open, public space for citizens or yet another space of transition for cars and tourists.

In the centre of Tbilisi lies the Rose Revolution Square, named after Georgia’s Rose Revolution of 2003. The place has changed a lot during the past decades, but still retained its character as an important part of the city. On the sunny 26th of May in 1995, the Georgian air force planes created a spectacle for the crowd that had gathered for Independence Day. Still called Republic Square back then, the square itself was also the setting for a military parade in celebration of the Georgia’s independence, which it gained shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Although the air still contained the strange scent of war on that day in 1995 after a severe civil war, the young independent country was rejoicing. Yet, right in front of the audience stood the run-down Hotel Iveria, which was now home to over 800 Abkhazian refugees as a silent reminder of the recent conflicts. In fact, that very place had been a battlefield only a few years earlier.

Almost two decades later, the square is mostly home to noisy traffic and vast empty spaces. The hotel has been emptied of the refugee squat, had a modern renovation and now belongs to the Radisson group. While the square is geographically exactly the same, a lot has changed. The place is not only one of Tbilisi’s few public squares, it is also arguably the place where the political and social transformation are most deeply reflected in urban space and architecture. Here, the country’s and the city’s recent past and present are visibly mixing, creating an absurd, mostly unused transitory space in the heart of town.

The story goes back to 1960´s, when Soviet Georgia was one of the top tourist destinations of the USSR. In 1967, the construction of the tallest building in Tbilisi was finished: Hotel Iveria, a 22 storey high structure designed by the Georgian architect Otar Kalandarishvili in the very geographical centre of Tbilisi and well visible from every point of the city. This prestigious Hotel was clearly not accessible to everyone. In order to book a room one had to make a reservation several months in advance through the official travel agency of the Soviet Union “Intourist”. Only the lucky ones would be able to stay in one of the rooms with a great view overlooking the entire town. Along with the hotel Mr. Kalandarishvili also designed the square in front of the hotel, which was finished much later, in 1983. As described by the architect himself at the time: “In the centre of the city, one of Tbilisi’s most important squares will be established by levelling an existing dip. The so created space underneath the square will contain more than 20 thousand square meters of useful space on three levels that will be used to create a social-cultural centre”.

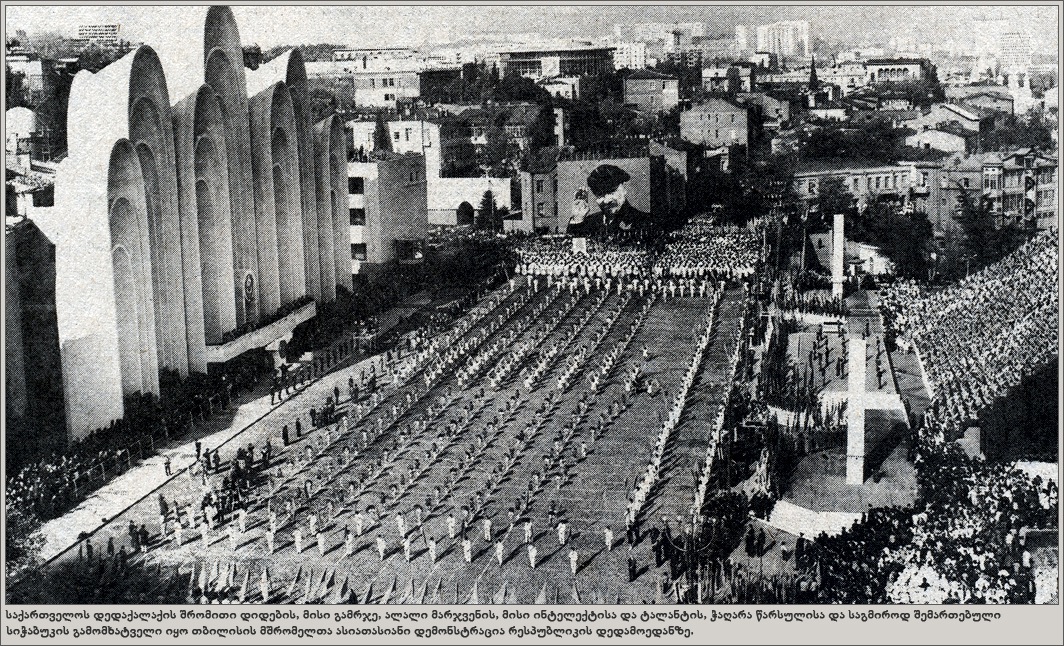

The architect had the intention to redesign the city, creating a dimensionless open space and a new central square in Tbilisi, a space dedicated to the popular public gatherings. On the weekends the former Republic Square was to be converted into a pedestrian zone. One side of the square was designed with a podium, standing tall with seven arches – the so called Andropov´s Ears – while the other side of the space was endlessly expanding into the horizon, overlooking the city and the Kura River (Georgian: Mtkvari River). Above ground, space was planned for parades and public gathering, while underneath it was extended with a 3-storey space and passageway dedicated to cultural and commercial activities. Simultaneously, the entire open space was to play an important role in handling the increasing traffic in Tbilisi at the time. Cars were allowed to go in every direction, even up and down the hill, the plan paying little regard to pedestrians. But as a matter of fact, the original plans of the square along with the underground passages never fully came into reality and indeed, many of the planned features will forever remain only in the architect’s visions.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Republic Square remained unchanged and continued to host state military parades just as before. However, it was to become one of the epicentres of the Georgian civil war in 1991-1992. As a consequence, the formerly prestigious Hotel Iveria also changed into a theatre of war and later, in 1992, became home to hundreds of refugee families from Abkhazia. Once a fancy hotel in the heart of the city, it was now turned into a vertical refugee camp. Many of the war’s internally displaced people settled here, trying to create a temporary place to live – a situation that lasted for more than 10 years. Certainly, during that time the temporary residents of the hotel changed its architecture in order to create a liveable space, giving the building its distinct look from the outside. On the inside it was very packed, dark and dense, as someone who visited the place in 1997 explained. He also mentioned that it was considered a dangerous place to go, so visitors would not stick around longer than necessary.

The Hotel remained a dark spot of the city and a constant reminder of the country’s problems of the past and also the present. After the Rose Revolution in 2003 the new government started to be concerned with the on-going uncontrolled construction in the city. According to the new president Mikheil Saakashvili it was to be emptied of its inhabitants and restored to its original condition as soon as possible. In 2004 the internationally successful Silk Road Group that owned the hotel already since 1994 began moving its inhabitants out and started a huge restoration process. Only the skeleton was left from its original structure – and what was once considered an important monument of the city had lost its distinct look, yet again. The refugees living in the hotel were only given two months to move out and to find another place to live, together with 7,000$ per room for compensation. The new government promised to also renovate the whole area around Hotel Iveria, including Republic Square.

The Silk Road Group who owned both the Hotel and adjacent Republic Square appointed the Berlin/LA/Beijing based architectural bureau GRAFT to reconstruct the building into a fancy 5 star Radisson Blue Hotel, which was pompously opened in October 2009. The project authors describe the newly redesigned building of the Hotel as a new landmark and a beacon of optimism for the future of Georgia. Again, reconstruction of Rose Revolution Square took slightly longer and started two years after the opening of the hotel in 2011. The Portuguese-Georgian architectural studio called NOA, who was put in charge of the project realization, describes it as follows: “Refurbishment program of RRS implicates the development of recreation zone surrounded with vegetation, a pavilion type cafe and ice-cream shop, fountain with water mirror pool and a parking area.” However, the same studio also conducts the construction of a commercial, multifunctional building on the square. Ironically, this building is to be built at exactly the same place where the podium was situated before from where one could watch the military parade dedicated to the independence of Georgia.

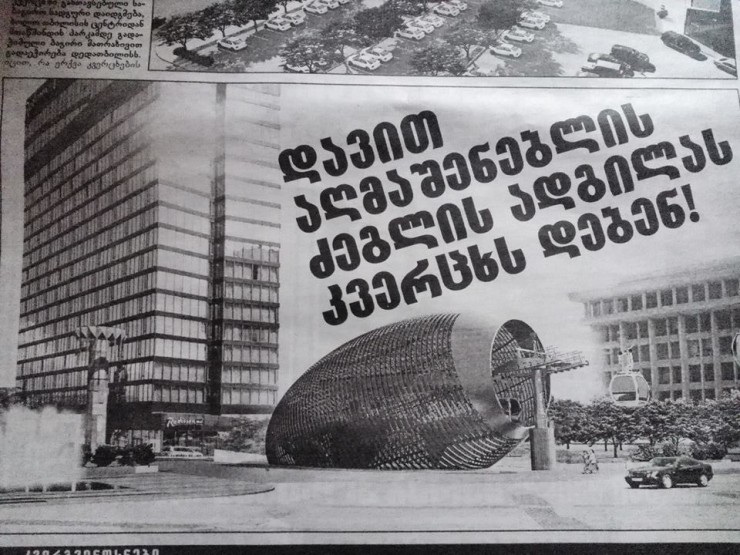

Different governments have used the former Republic Square to show their political power by renaming and redesigning it. As political powers change, even the pre-existing monuments on Rose Revolution Square keep disappearing and re-appearing with a new look. In 2005 the recently elected, west-oriented government of President Saakashvili also ordered the destruction of the so-called Andropov’s Ears that had become a symbol of communism (named after Yuri Andropov, General Sectretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) and had a reputation as the most hideous soviet monument in Tbilisi. Noticing that these arches are just one example on a much longer list of buildings that are to be erased from the face of the city, Tbilisi’s architectural and cultural circles have made the square a topic of debate. Today, a large number of architects and intellectuals are fighting against the construction of a cable car station on Rose Revolution Square. Planned during the rule of former President Saakashvili who also ordered the evacuation of Hotel Iveria, the cable car would connect the centre of Tbilisi to Mtatsminda Park – a large amusement park on top of Mtatsminda Mountain. With a station placed in the middle of the square, it would once again change its look and also the face of Rustaveli Avenue, the city’s main street, tremendously.

Today’s Rose Revolution Square was originally built as a large space to host soviet military parades, public gatherings and to handle the city’s increasing traffic. As the square was built on steep terrain like an urban balcony, it was to offer a wide-open view of the river to anyone – just like from one of the exclusive rooms of Hotel Iveria – and also to provide space for culture and education. After Georgian independence and a destructive Civil War any traces of the soviet past were to disappear. As many other buildings and places in Tbilisi, the Rose Revolution Square has also suffered the consequences of the erasure of any traces of soviet times. Today’s new government is again changing the space, recently removing another monument and opening Iveria Café. So, ironically by trying to change the situation, history just keeps repeating itself. In a constant state of mutation, various notions of space that are present in the memory of the locals are overlapping and preventing the place from becoming a functional public space.

Indeed, Rose Revolution Square may thus be considered a showcase of political ambitions and showing the direction the nation is heading. The square remains a space in Tbilisi, but a space that just is not used by the greater public. Most of the surface is still reserved for cars and the huge space located underneath the square has become a dubious space occupied with small businesses, offices, strip clubs and brothels. Just as in the 90’s when the place was the nations epicentre of underground culture – exactly because of it´s underground location – it still doesn’t seem to fit in the picture of the square that politicians are trying to implement: a sanitised, commercially oriented space. Perhaps, the one thing that has not changed since the early 1990s and that will probably stay the same in the future is that while facades, monuments, buildings and even names are easily altered, the people of Tbilisi will follow their very own individual logics of integrating the square into their every-day life.