Last week marked the thirtieth anniversary of the end of the 1984-5 British Miners Strike, the longest industrial conflict in the country’s history and, with retrospect, the critical turning point not only in the UK’s labour relations but in its de-industrialisation and in its economic transition, land use, architecture and the very structure of its society.

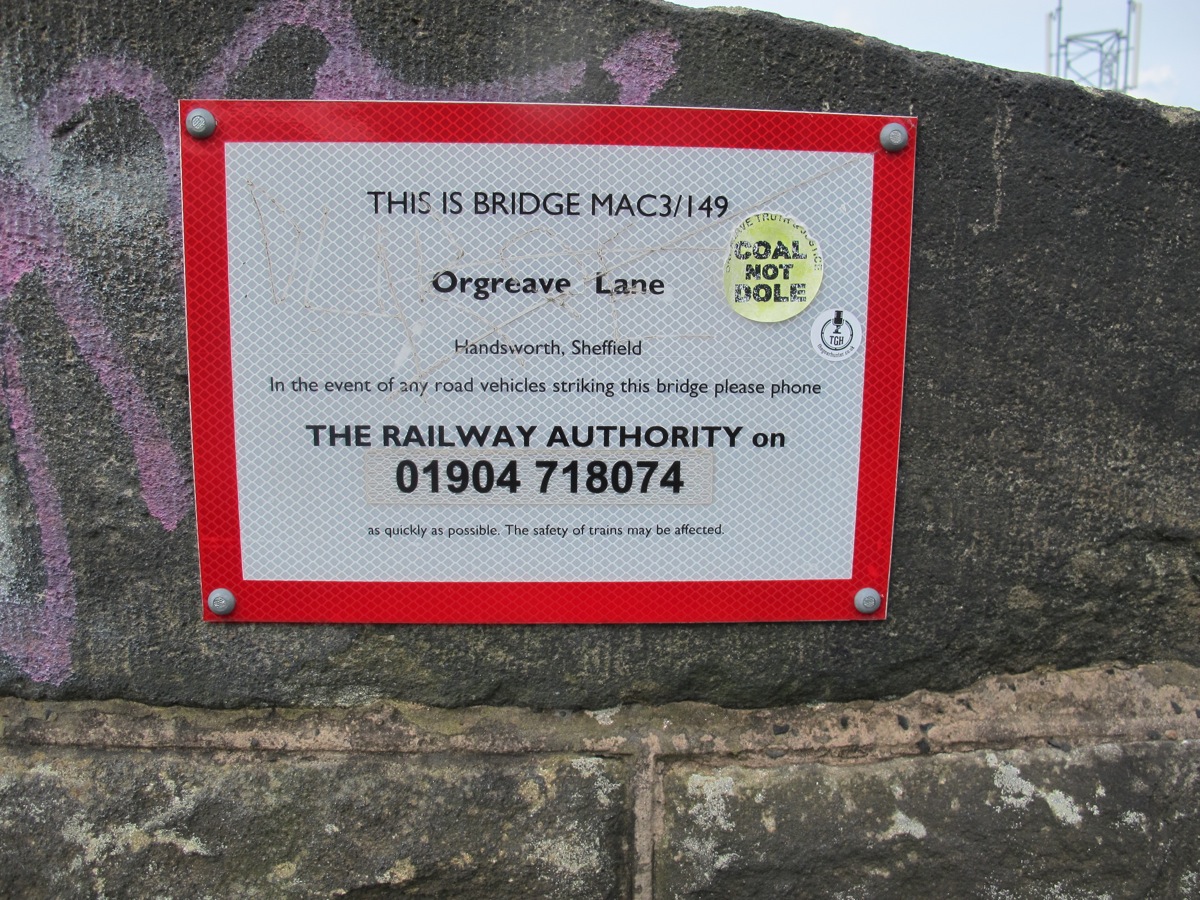

The anniversary has not passed unmarked, memories erupting among the defeated mining communities that returned to work in March 1985 to face the subsequent waves of pit closures they had suspected amid government denials and fought against. In 2012, in the wake of the official apology from the Prime Minister for South Yorkshire Police’s failures and lies about the Hillsborough disaster, the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign formed, demanding an enquiry into the day that formed the bloody pinnacle of the Strike. Within two months, that same police force had referred itself to the Independent Police Complaints Commission; a decision whether to investigate remains untaken two years later. In September 2014, Pride was released to popular acclaim and a BAFTA win, telling the story of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners, while a new documentary Still the Enemy Withinrecorded the testimonies of miners of the events of 1984-5.

The forces that defeated the miners also remain, albeit transformed, and they too remember this past.

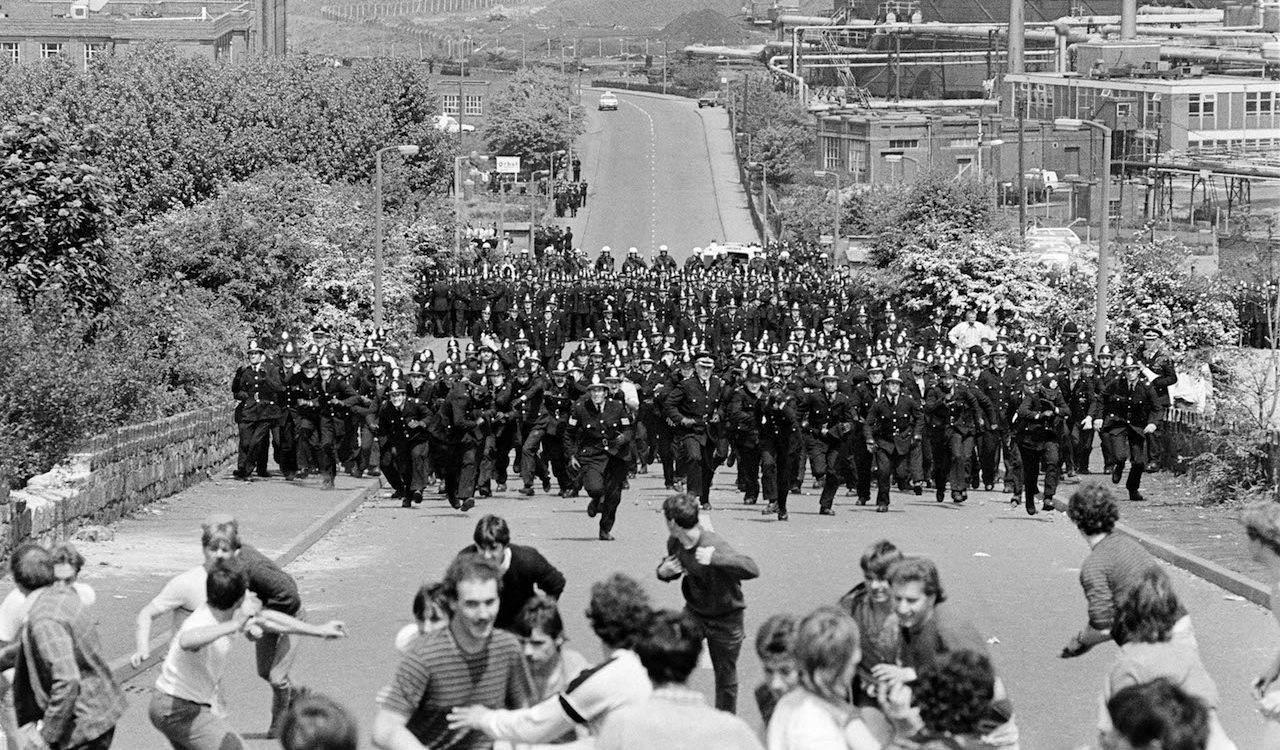

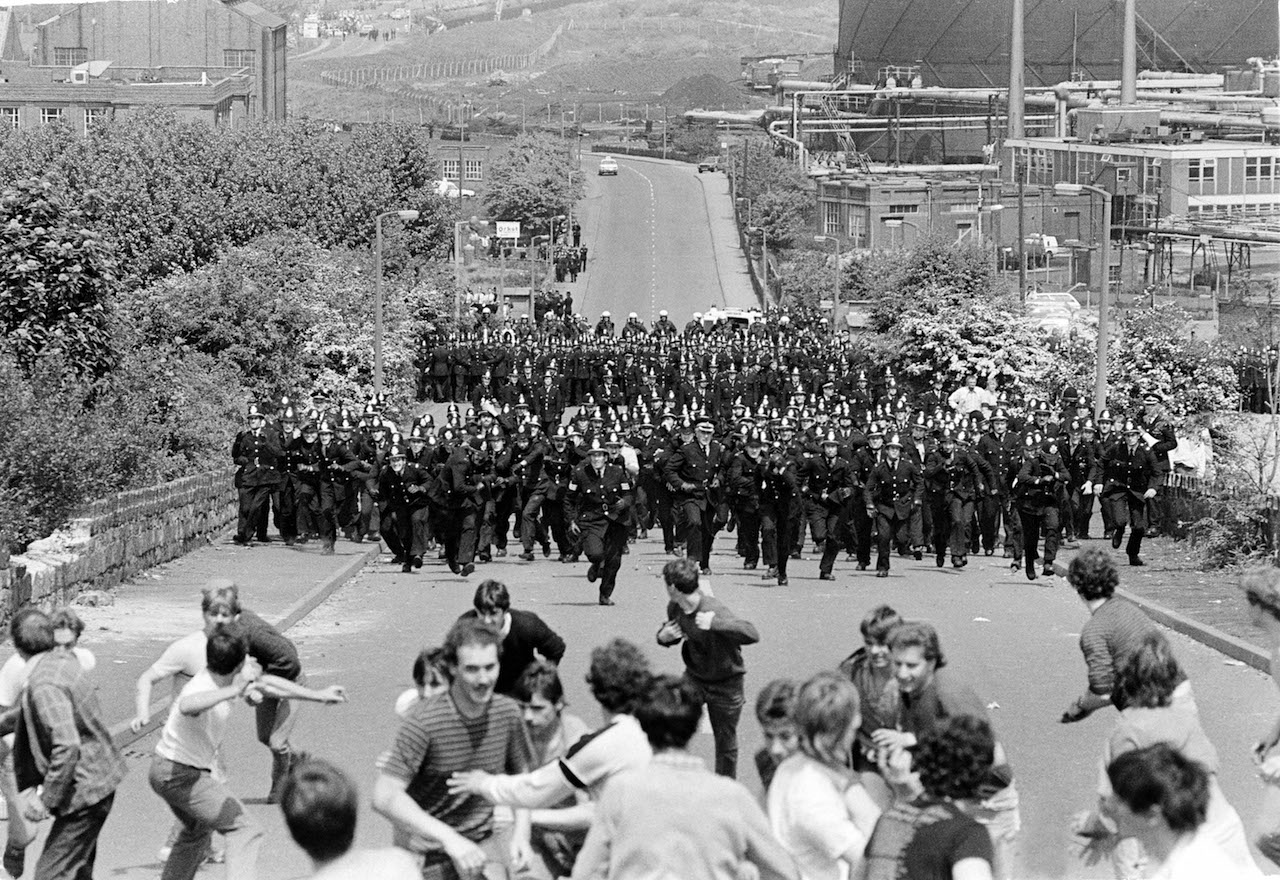

There is nowhere where this is clearer than Orgreave, South Yorkshire, site of the event that arguably symbolises the struggle. A coking plant here produced purified carbon fuel for steel production in a semi-urban secondary industrial wedge south of Sheffield and Rotherham. It was of strategic importance to efforts to maximise the Strike’s impact on the reliant industries and on 18 June 1984, pickets claimed they were directed to the site, chosen for the clash with heavily armed riot-police. The Truth and Justice Campaign render bitter memories of brutality and a sense of injustice on the part of veterans of what has become known as ‘the Battle of Orgreave’ undeniable. The police and BBC stand accused of false testimony in what Michael Mansfield QC, the lawyer of almost one hundred Miners later acquitted of ‘riotous assembly’ called ‘the biggest frame up ever’.

2014-5 has coincidentally seen the final demise of deep coal mining in the UK. The bankruptcy of UK Coal PlC, the successor upon the 1987 privatisation of British Coal’s assets, completed transformation from a nationalised extractive industry to private-sector property development, a corporate distillation of the UK’s macroeconomic conversion since the Thatcherite transformation of the 1980s.

This repurposing follows a major conversion of the purpose of land assets, from the extraction of quantity to qualities of place, value re-embedded by regeneration and placemaking. UK Coal’s property subsidiary, Harworth Estates, the only profitable arm of its business, is charged with decommissioning, decontaminating and developing the former coalfields.

Now, this location is again strategic given its situation, increasingly centralised within an emergent city-region by what Jones the Planner has described the “Meadowhall-isation of the conurbation”, a centralisation of the periphery to be compounded by the planned High Speed 2 rail route following the M1 motorway alongside the originally out-of-town 1990s shopping centre. Post-privatisation, the state remains an active partner at Orgreave, stimulating regeneration in the form of multiple policies and public sector local economic development bodies, deployed since the 1990s. This rescaled public-private focus on a competitive city-region has seen Orgreave designated as the flagship site of Sheffield’s, South Yorkshire’s and even ‘the North’s’ industrial recovery.

Planning is always a political, social and linguistic endeavour saturated with conceptions of time, it consecrates a future in the present. Discourses of regeneration propose a further perspective on a failed, expired past. In these activities, the forces that defeated the Miners, state and capital now refocused on property development, have their own, quiet practices of narration over the events of the Strike. The will to present an official narrative was overtly acknowledged, a now-removed website where Harworth Estates presented the new suburb for consultation and planning purposes, directly addressed the site’s past:

Orgreave Colliery rose to national prominence during the 1984 miners’ strike as the scene of a famous stand-off between police and miners. Development at Waverley will aim to provide sensitive reminders of this historic past, while looking confidently ahead to renewed progress in the 21st-century.

This “renewed progress” is presented in economic function, landscaping and, most intriguingly of all, the decision to rename Orgreave as ‘Waverley’.

This renewal of progress was envisioned as a continuity of land use, a rebirth of the decimated industries of steel and energy production, now updated and specialised, globally competitive, clean and sustainable. In the mid-2000s, Harworth Estates, with considerable support, established the Advanced Manufacturing Park, with a University partnered Research Centre as a locus to create a cluster of high-tech, specialised steel and manufacturing firms. This strategy marries local legacies of the past, the residual knowledge economy that outlasted South Yorkshire’s dual economy of coal and steel, with a vision of successful competition in the future. To date, this has been largely successful, with Rolls-Royce and Boeing anchor partners in the park. Re-industrialisation then provides the anchor employment to the second phase of development, a new suburb, currently being built out by the UK’s leading large housebuilders, working in partnership with Harworth Estates.

The other renewed function of place, energy production, is conspicuous. Two large windmills stand among the gleaming factories, visible from the dual carriageway that links Sheffield to the motorway. These new landmarks replace the once spinning pitwheels, the symbolic architecture of dirty, toxic coal, windmills the optimistic emblems of a future that underline the unsustainability of past ways of production and with it, the necessary end to ways of life and labour, the loss of which remains resented.

Amid this architecture of environmental necessity, it is worth remembering the threat of climate change and the impossibility of a coal based future were not contemporary motives for the plans to ‘modernise’ coal which were met with industrial dispute, Thatcher spoke of economic rationale, readying the industry for global competition and profitable privatization. While the UK has abandoned coal extraction since the Strike, electricity production did not follow, instead importing to the UK’s fifteen remaining coal powered stations. As a result, the rhetoric and devices of sustainability appear environmentally empty but politically loaded, reframing ‘the enemy within’ as Thatcher famously described the National Union of Mineworkers from class to carbon, the enemy now environmental, that of our sustainable future.

The expired architecture of coal mining and coke extraction were quickly demolished after closure, negating any possible future existence of ruins, and with them the ‘anarchic spaces’ of disorder, haunting and contestations of the past the geographer Tim Edensor has identified in his extensive surveys of British industrial ruins. The noted disorientation for veterans of Orgreave who have returned is confirmed by the removal of significant parts of the road network, the last fabric of the urban in this former peripheral industrial zone.

The only structure remaining from 1984 is a bridge across the railway line that forms the western boundary of the development site and over which the pickets were chased by police horses. The bridge is suitably ruined and fenced off, but now lies adjacent to and largely obscured by a heavy-duty replacement, presumably too prohibitively expensive to remove. As a result, the sight is an almost archaeological presentation of time as strata of engineered infrastructures, a Victorian brick bridge obscured by its concrete and steel twenty-first century replacement, forming an unintended monument to creative destruction and the re-emergence of infrastructure investment, desire for ‘renewed progress’ displayed.

Coalfield regeneration begins with intensive decontamination processes that achieve a tabula rasa and transform even the physical landscape beyond recognition. This is achieved as by-product of open-cast mining, gleaning the last profitable shallow coal from the surface. With this, it is the soil washing of industrial contaminants that transforms topography as the entire terrain is removed, washed and replaced, with significant hydrological and other environmental consequences. ‘Waverley Hill’ is entirely artificial and new, housing a buried steel container of contaminant material washed from the soil as by-product, the poisons lingering from past use now safely locked away.

This sorting of the soil, stripping out toxic traces mirrors a transformation of Orgreave beyond material. Post-structuralism and a ‘linguistic turn’ in human geography have emphasised the role of language in building places, examining re-naming strategies deployed by the powerful as a form of remembrance and where required, amnesia. This critical toponymy illuminates the recent renaming: ‘Orgreave’ is similarly tainted, the evocative signifier of the Strike. This was heightened at the time development began. Orgreave was arguably consecrated as a ‘Battlefield’ by Jeremy Deller’s 2001 Turner Prize winning re-enactment The English Civil War Part II, the title revealing a statement of historicising intent and heightened contemporary cultural notoriety, confirming ‘Orgreave’s’ threat of recall in the eyes of developers keen to create ‘confidence’ in industrial space and a successful suburban community. Just as the topography undergoes topographic decontamination, place name required ‘toponymic cleansing’.

Although the preference to remove ‘Orgreave’ is probably self-evident, the new name for the new suburb, ‘Waverley’ represents a curious positive choice in itself, albeit probably an unconscious one. Representatives of Harworth were unable to provide a reason for the positive choice, corporate memory perhaps understandably lost along ten years of planning and development. The name does have some existing connections to the area, a Waverley Coal Company operated here around 1900, an overlooking street in the neighbouring suburb of Catcliffe, Rotherham, named ‘Waverley View’. The origins of these names, which predate regeneration, are unknown and may be the simple explanation for the choice.

Nonetheless, perhaps only on this basis of coincidence, the uncanny appears to lurk in language. The Sir Walter Scott novel Waverley, from which specific connotations have emerged in both the English vernacular and its significance within literary criticism, could have been the influence, the author’s connections to the region strong, the location for another novel Ivanhoe. The Penguin Classic edition’s introduction to Waverley states it has had, since publication in 1814, ‘the curious immortality of giving its name to places and institutions throughout the English speaking world’. ‘Waverley’ has long been used as a place name for colonial settlements, Edinburgh’s second rail station and even a Surrey Borough Council in 1974.

This designated function, to signify the new, emerges from the novel itself. In its first paragraph Scott justifies the choice for his protagonist as ‘an uncontaminated name, bearing with its sound little of good or evil, excepting what the reader shall be hereafter pleased to affix to it’. This explicit allusion of ‘uncontamination’ from literature reinforces the distinct parallels to the material and memorial processes undertaken by the developer at Orgreave. But of even greater intrigue, it is a novel about a civil war.

It is possible an employee had read it. Waverley was steadfast on British school and undergraduate literature curricula for much of the twentieth century and given its age, it has been asserted as the most read English novel of all time. The literary critic Georg Lukács characterised Waverley, published seventy years after the Jacobite Uprising of 1745 it is set against as “the first historical novel” in that national events, the political and economic transformations of the Anglo-Scottish Union force transformations of character and plot development.

The novel follows Edward Waverley, an English aristocrat and officer who acquires sympathies for the rebellious Jacobite clansmen while stationed in the Highlands. The author attracted Lukács’ praise for ‘historical realism’, his politically surprising sensitivity towards the clansmen:

This sympathetic stance also intriguingly generates strong parallels to be drawn with the Miners’ situation, perhaps a tribute to the nobility of a community that fought the managed decline of the coal industry during the Strike, who weather the economic, social and human consequences of its loss ever since. In this respect, even if an unconscious choice, ‘Waverley’ not only signifies the historicising potential of fiction but the name may provide the platform for the most sensitive remembering of the Strike at Orgreave.

There are no plans for an explicit memorial to the Battle. Instead, Harworth Estates have commemorated the site’s past visibly in feature walls designed as entrance gatways to the residential suburb. These dry-stone walls feature corten steel fins, their weathered rust colour chosen to embody iron ore. Amid the stones lies a darker solid band, to represent the coal seam.

These representations of the materials of local fortune, iron, coal and from them steel, symbolize the site’s and region’s past gains from coal. These regional material motifs also present a slow, long view of time, evoking the geological processes of fossil fuel formation, reaching back into the pre-historic. This aesthetic presentation of time, place, and a “historic past” is a sensitive reminder of coal, not the Strike, living memory diminished in this visual narration. Instead the region’s original and proclaimedly refound and renewed sources of strength are emphasised, the recent trauma of de-industrialisation minimised, to merely a dark chapter within a longer, optimistic history that now stretches equally lengthily into a projected sustainable future. It is in this representation that Harworth Estates believe provide ‘sensitive reminders’ of not only the site’s past, but their own corporate identity.

Regeneration always deals with failure, but rarely is this so plainly difficult, nor dealt with by victors, as at Orgreave. As a result, this case study reminds us regeneration is always an inherently ideological activity, where power, through a range of mechanisms, designs, narrates and displays a version of the past, oriented to an imagined future, responding to the needs of the post-industrial, neo-liberal present. At Orgreave, the official promise of this progress is explicit. The devices of anti-heritage that underline this, linguistic and material, reveal the ongoing priority of capital and state, attempting economic recovery to ‘sensitively’ deliver retrospective political, economic and environmental justification for, and ultimately the forgetting of, the trauma of recent failure.

But traces of Orgreave remain, not least linguistically, on street signs and maps. So contestation in place remains possible. Since the twenty-fifth anniversary, members of Women Against Pit Closures return to the site annually, tying suffragette ribbons to the second bridge, new infrastructure co-opted to house the symbols of new identities found by many during the Strike. These returns expanded to a festival supporting the Justice Campaign in 2014, held in a recreation ground adjacent to the development. The adjacent, mutually oblivious practices of memory, ritual and regeneration, confirm that this official promise of progress does not penetrate the mining communities that survived the Strike to face pernicious unemployment and deprivation. The optimistic, projected future, as willed for at Waverley, will not benefit them, nor fulfill their enduring desire to gain truth, justice and ultimately peace.