Friday, 28 January 2011. Three days after the start of mass demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, protesters called for a ‘day of rage‘ to invigorate the demands of a nascent revolution. After midday prayers, up to a million people descended on Tahrir square from all corners of the city, resulting in a long day of bloody fighting with the police. As the evening fell, the police seemed to be losing control in most places and started to retreat from the streets. While protesters entered Tahrir square, news agencies made their first reports about a fire at the headquarters of former president Hosni Mubarak‘s leading National Democratic Party (NDP). The building, located between the Nile and Tahrir, had become a symbol of 30 years of oppression and was suddenly burning spectacularly, lightening up Cairo’s evening sky.

Until today, it is unclear whether the NDP-building was set on fire by protestors, or by someone who wanted to erase all evidence of decades of dictatorship. What did become clear the next morning was that the physical manifestation of a much hated regime had turned into a heavily scarred ruin. The charred, concrete skeleton was still standing and would from that day on overlook the rest of the events on Tahrir Square, from the joyful celebrations as Mubarak stepped down on February 11 to the violent clashes that would follow in the years to come. Its prominent position in the urban landscape has always made the building impossible to ignore, but from January 2011 onwards it would also constantly remind people, from commuters on the 6 October bridge to tourists visiting the adjacent Egyptian Museum, of Cairo’s recent history. In particular in recent times, with demonstrations in Tahrir becoming increasingly rare, the former NDP-building seems to have become the most obvious memorial to a landmark revolution.

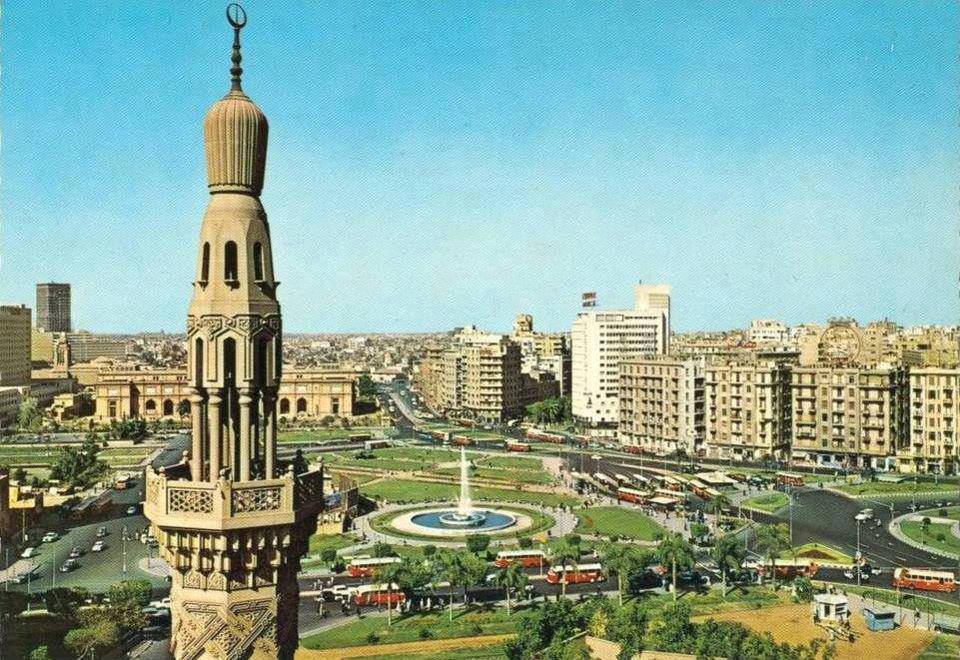

Tahrir square has been a symbolic place since the 1919 uprising against the British occupation and has remained a stage for high profile political events throughout the last century, from the 1952 revolution to the Iraq war demonstrations in 2003. The square started to get its current shape when Cairo’s late 19th and early 20th century urban expansion schemes, currently known as ‘Downtown’, were extended towards the Nile, which included the 1902 construction of the famous, pink-orange Egyptian Museum in neoclassicist style. The new square was cut off from the Nile by the British army’s extensive barracks, which kept a controlling military presence in the middle of the city for a long time. The south side of the square was shaped by the construction of the monolithic ‘Mogamma’ complex in the late 40s, which has housed government offices ever since and became a ludicrous symbol of a slow and incompetent state bureaucracy. In the same years, the British vacated their army barracks, which were torn down not much later. This provided Gamal Abdel Nasser, who became the first president of the newly independent republic in 1953, with ample space to construct the capital’s future skyline.

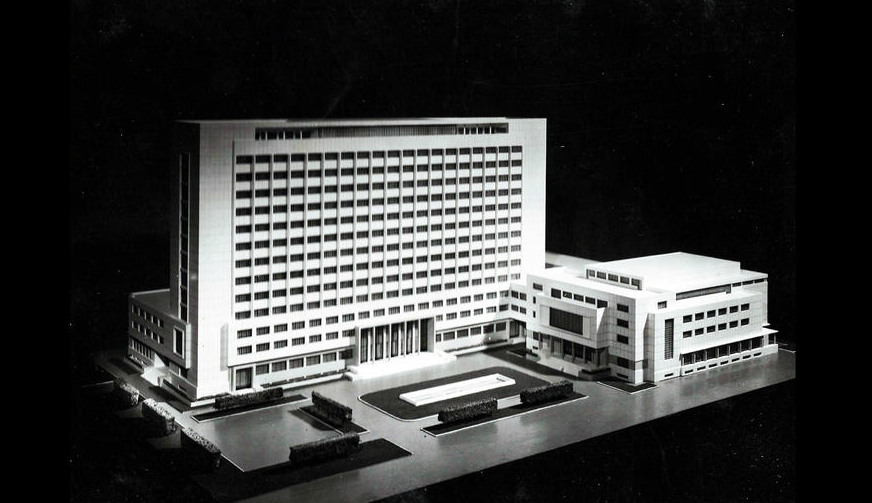

In the first years of Nasser’s rule, three new landmarks would be added to the square, all involving the productive Egyptian architect Mahmoud Riad. The modest Arab League Building, housing an organisation that clearly fitted Nasser’s pan-Arab ambitions, was the first to open in 1956. The more impressive and high-modernist Nile Hilton Hotel followed a few years later, which was co-designed with the American architect Welton Becket and was the second Hilton to open outside the United States after Istanbul. The final addition to the square was another overtly modernist construction, built just behind the Egyptian Museum in 1958. Originally designed to house the Cairo Municipality, it was at completion quickly occupied by Nasser’s Arab Socialist Union (ASU), the only legal political party at the time. A few years after Nasser’s death in 1970, the role of the ASU was succeeded by the National Democratic Party (NDP), founded by Egypt’s second president Anwar Sadat. Despite Sadat’s aversion of the ASU, its politics and and Tahrir premises, he moved the NDP into the building, where it would remain to the end of Hosni Mubarak’s thirty year reign.

All three buildings can be considered as striking products of the architectural ideas of their time, and all were listed a few years before the revolution. Despite being built by the same architect in the same period, the modernist additions to Tahrir didn’t form much of an harmonious ensemble however. All three of them were built in a slightly different style, with the former Nile Hilton the most notable outsider, and all were surrounded by a chaotic collection of loosely positioned side-buildings, undefined objects and fences. Their current state doesn’t help much either, especially since the NDP-building is being demolished and the Nile Hilton hotel is being renovated by the Ritz-Charlton chain in a way that is seriously damaging the original design. As long as part of the NDP-building is still standing, Nasser’s skyline gives Tahrir square its dramatic, but slightly unbalanced backdrop, as well as its current, rather undefined shape. While a recent, post-revolutionary renovation of the plaza in front of the museum hasn’t done much to improve the quality of the area’s public space, the demolition and subsequent transformation of the NDP-site might drastically change the square.

Already within months of the beginning of the revolution, the future of the NDP-building was ardently debated. Before the beginning of the demolition, Cairobserver already argued that its structure was probably still in good shape and that it could (and should) be preserved. Interestingly, both revolutionary groups as well as supporters of the now defunct NDP agreed, with the former hoping to turn the building into a monument or even a museum of the revolution. Architecture and heritage professionals from the National Organisation for Urban Harmony have also argued against its demolition, quoting its listed status. Mahmoud M.M. Riad, grandson of the building’s architect and head of the family business today, even started a campaign to save the building and drafted a proposal for its adaptive reuse. While suggesting future functions such as a five star hotel, a research center or, after more than half a century, finally the headquarters of the Cairo municipality, Riad noted that a thorough renovation would not have excluded the possibility of keeping a prominent reference to the building’s recent history.

While there was indeed a fair bit of support to keep the building, most people didn’t seem to mind it being torn down. In particular the board of the adjacent Egyptian Museum was keen to see it go. The NDP-building was build uncomfortably close to the museum and the board has plans to realise some pleasant gardens next to its premises. Others argued that the demolition of the building would create the opportunity to finally connect Tahrir directly to the Nile waterfront. Whatever people’s opinions, it seemed quite unlikely that Egypt’s current regime, headed by coup leader turned president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi since the summer of 2013, would take them into account. Not only has the regime become more confident to rule as it sees fit in recent times, it also owns the building and the land since all NDP’s properties and assets reverted to the state after the party was dissolved by court order in April 2011. Although officials have briefly mentioned a plan for a revolution-memorial-cum-botanical-garden, the government has in recent months been speeding up procedures to officially delist the building, among others by coercing the responsible organisation. In the spring of 2015 it was announced that the building will be demolished by the army’s engineering authority and probably be replaced by a public park.

In the last days of May 2015, workers suddenly arrived on the site to begin with a demolition process that will take at least three months. In the end, the NDP-building has not so much become the victim of a structural deficit or the Egyptian people’s lack of interest in modernist architecture, but rather of the successful attempts of the new regime to assert its authoritarian position and to erase all remnants of the revolution. All demonstrations are forbidden, the Muslim Brotherhood has been wiped out and revolutionaries are sentenced to years in prison or even death. A counter revolution is being implemented, which is masked by both a strong propaganda machine as well as, interestingly, all kinds of large engineering projects and spatial interventions. In March 2015, the NDP-building was temporarily covered with a life size banner announcing Egypt The Future, an economic development conference where plans for a new capital city where presented. Since, it has also announced a new civil airport, the accelerated construction of the second Suez Canal and the re-opening of the Tahrir metro station, which has been closed for the last few years for ‘security reasons’. Although the banner and its delusional message of ‘progress’ did not survive a mid-spring sandstorm, the current regime seems unstoppable and the demolition of the NDP-building is yet another political, spatial and visual milestone in their struggle for power.