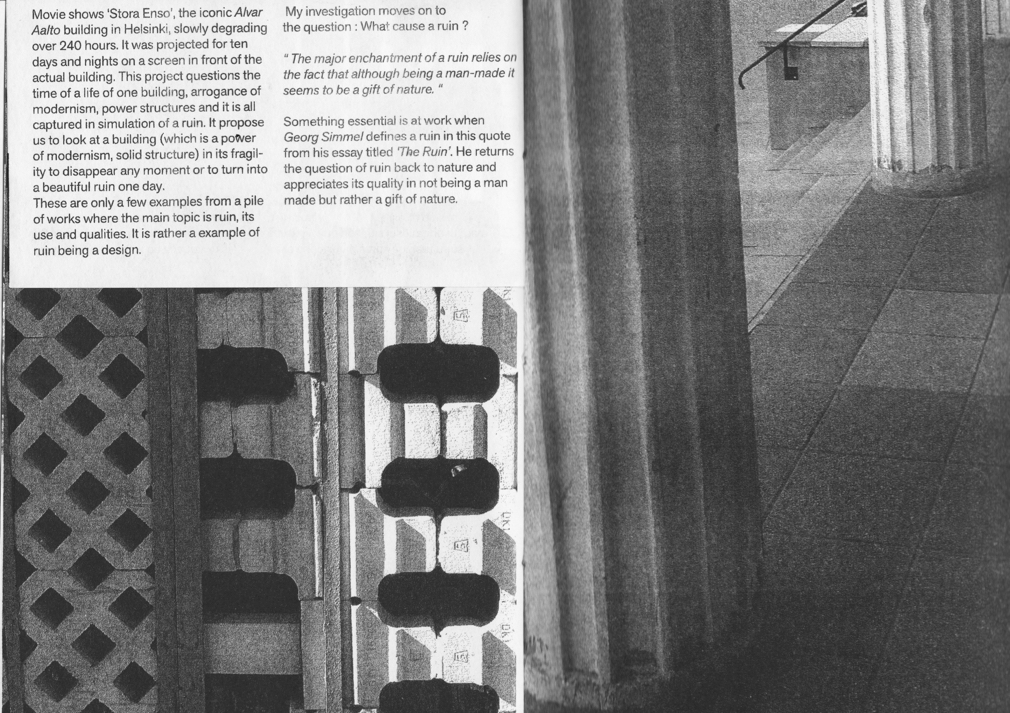

At Failed Architecture, we have of course published about ruins before. But we try not to revel in the great waste that an abandoned building invariably represents. Rather, we seek to analyse the built environment from various angles. For instance, a previous article that I wrote for this website does indeed celebrate ruins and urban decay. But I explore how they compare to a perfectly scripted urban space. These ruins, I argue, offer us an unusual space in which to breathe and to think. Through this, they have influenced artists and writers since at least the 18th Century.

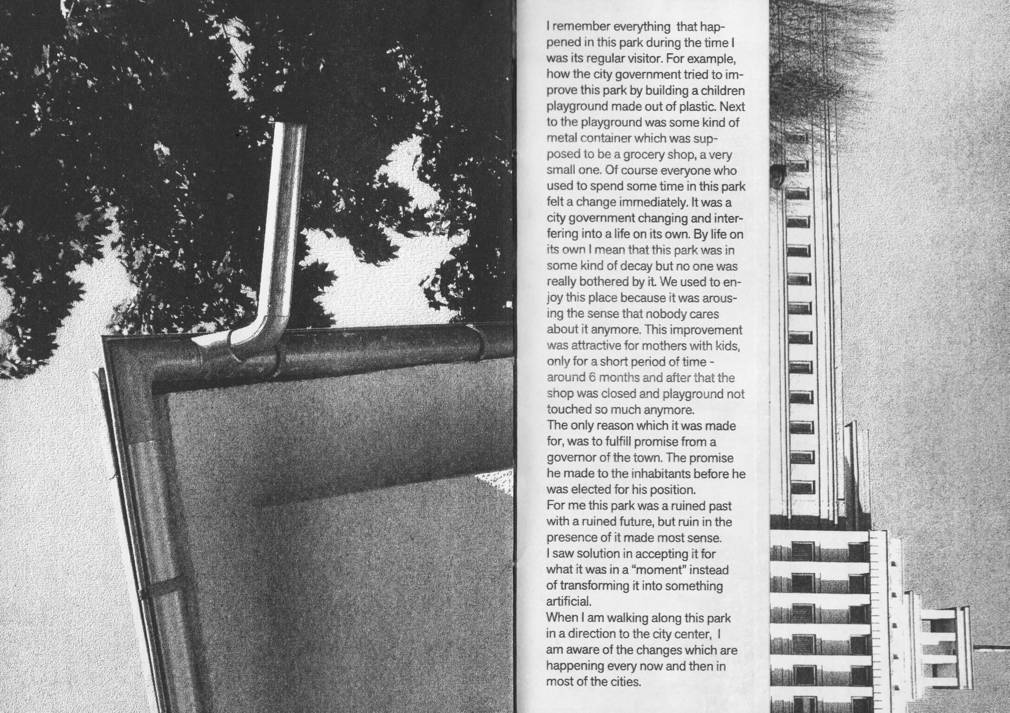

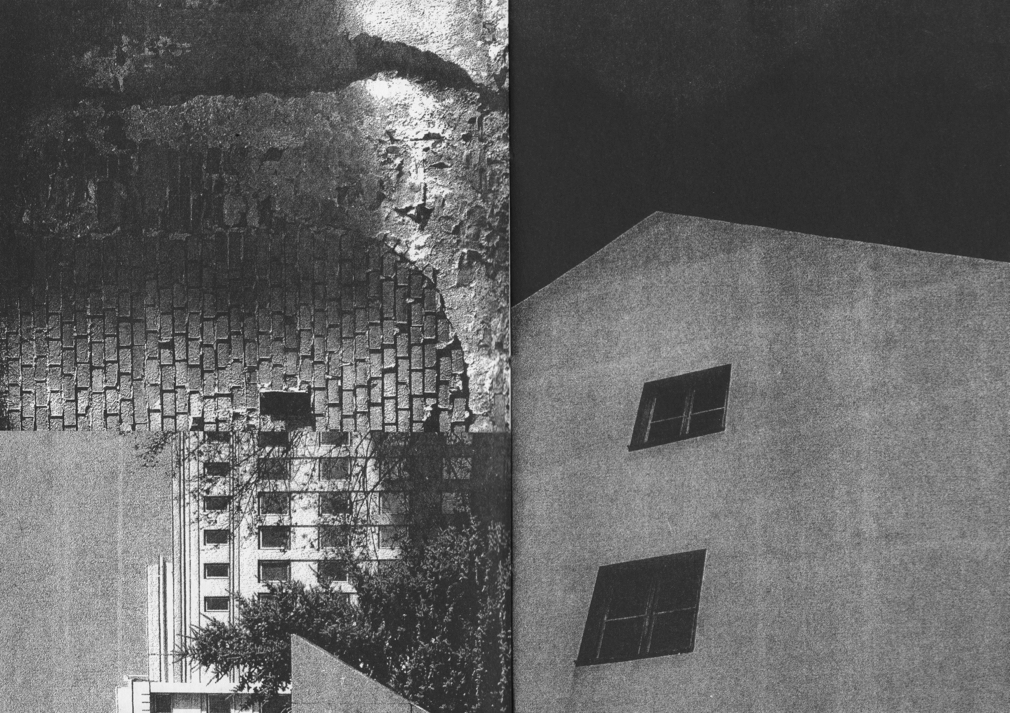

Slovakian artist Denisa Kollarova has also been preoccupied with ruins. The Rietveld Academy graduate returned to her childhood hometown and reflected on the ‘ruins’ she encountered there: the spaces and structures that she remembered which had become dilapidated over time. Her observations culminated in a book, consisting of text and photographic work. Rather than looking at ruins as useless spaces, she approaches them as places of potential, offering room for imaginations about the past and the future. For the publication she distorted the notion of real and visual spaces by collecting various spatial fragments, which, when combined, propose new additions to her visual memories.

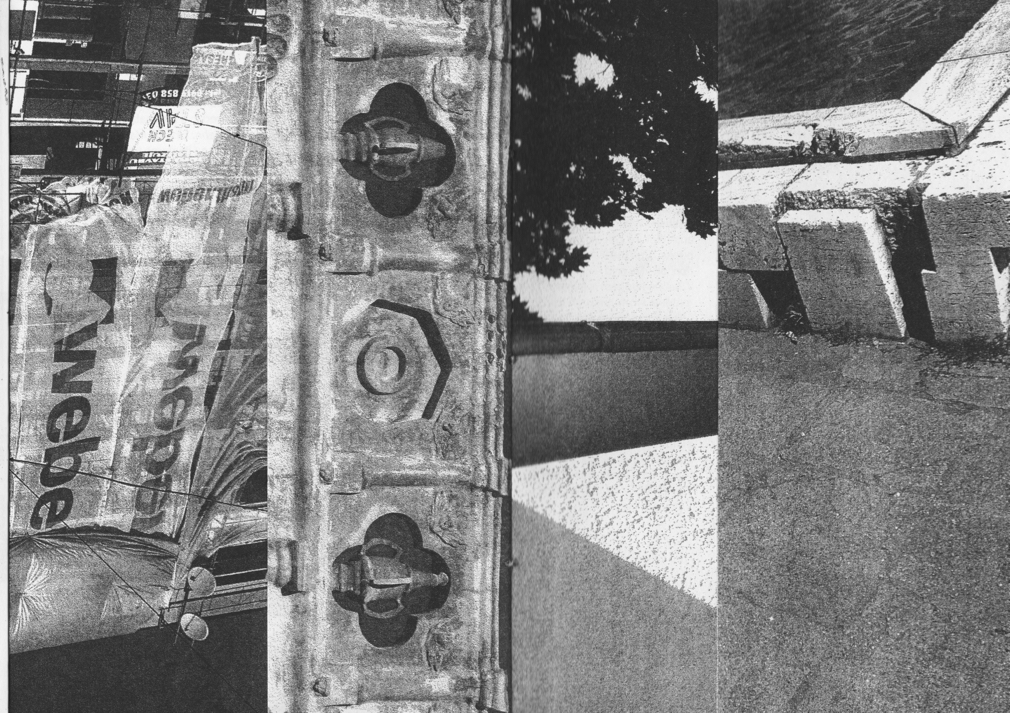

In the book she writes about a Communist memorial. “We used to enjoy this place because it was arousing in the sense that nobody cared about it anymore”. When I asked her to elaborate on this, she replied: “I would compare it to finding a broken toy: some kids are completely uninterested, whereas others like to repair it to their own taste and play with it. Creativity does not happen in places of perfection – not in the polished places without any mark of coincidence or natural feel. Creativity does not happen in the museum buildings – those clean and sterile spaces – but it happens in the studios and minds of artists. Only the results are shown in the museums.”

The book is mostly about memory, projected on (and perceived through) the built environment. Kollarova writes that her memory of the Communist memorial was that it embodied anything but a Communist memorial because hardly anyone knew what it symbolised. I asked her whether the current fetishisation of Communist memorials is mainly a Western thing, compared to the ‘lived experience’ that pushes their symbolic meaning, and their context, to the background. She said that she doesn’t see it as a matter of Western or non-Western culture: “I see it more as a question of generations with their habits of defining space by their memories of political struggle, and what a culture can make out of struggle and how to let go of it when a new generation sees a potential to define it for themselves. Once a new human is born into this world, we should provide him a book with blank pages in order for him or her to fill it in. It doesn’t mean that we have to erase history, but we are open minded enough to let new stories develop in the same space where our stories took place”.

Does she think that her experience of the halfway decayed monument is generally different compared to that of the generation before her? “Definitely! It’s a completely different experience. That’s also the reason why I do not believe in the fact that any building or space can be designed to be permanent. In my understanding of space and architecture, nothing is permanent, because the life inside, around, underneath, next to, and on top of these spaces is simply not permanent. A building is defined by the life which happens in it in this particular moment. The generation of my parents would be happy to tear many of the Communist monuments down to forget the regime. My generation doesn’t have that need, since we don’t have the same bad memories to dwell on. We look for another use of the space in the present.”

In the work she seems to conclude that ruins are more about potential futures than about nostalgia for the past. This especially goes for the observer who is not completely aware of the history of a place. He or she is free to dream up potential new uses of a space.

I ended by asking her whether she thinks history is a burden for people trying to take ownership of a space, or those trying to fantasise about alternative uses. “History,” Kollarova answered, “is what we learn and what people tell us. I think we should respect it, but we don’t have to dwell on it. It shuts down the possibilities of imagining something new, of being creative and giving places another chance through which bad memories can be healed.”