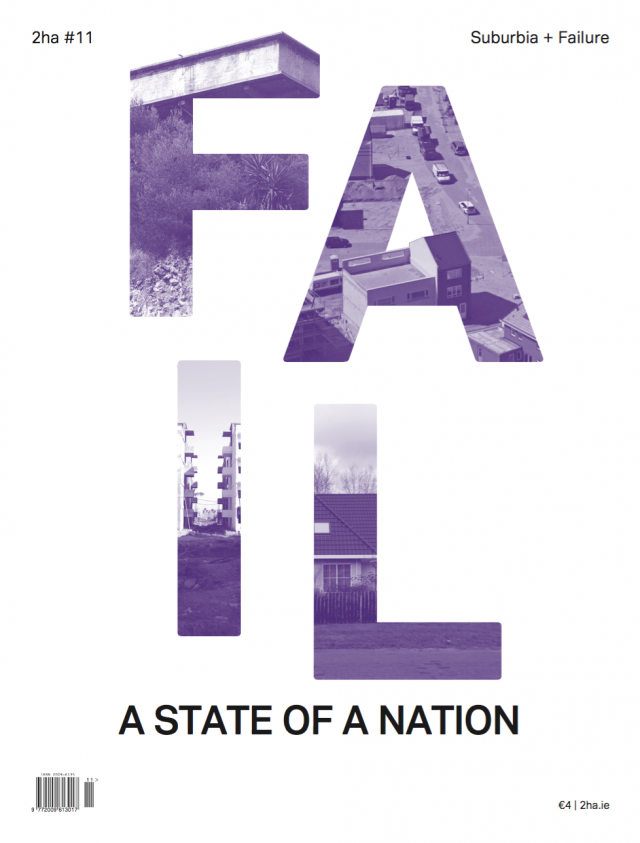

Introduction

As guest editors for this issue of 2ha, we formulated a blunt and naive main question: Did suburbia fail? This is obviously a problematic investigation since suburbia is too big to fail, too ubiquitous and multidimensional to treat as a singular topic, and impossible to define. Besides, it is subject to a variety of opinions and perspectives and no overview of suburban reflections can be exhaustive. Nonetheless, we posed the question, and asked people to respond to it with a short contribution consisting of either a 100 words text or a single image. We received more than 30 contributions from various parts of the world.

We didn’t expect a collective resolution, but sought to trigger a response from people with different geographies and backgrounds. Failed Architecture believes in a multitude of factors and opinions, and we are interested in uncovering the diversity and contradictions of the phenomenon called suburbia. We complemented the submitted contributions with a selection of quotes from experts and leading voices in academia, literature and pop culture. Suburbia is the focus of thousands of articles, books and other documents. In this cloud of perspectives, analyses and statements, we discovered some recurring themes and shared conclusions. Here we try to navigate through a wide-ranging collection of texts and images assessing the ‘state of suburbia’ with wit, anger and affection.

The contemporary conception of suburbia could be said to have started before World War II as an American ‘way-of-living’ and has since become a global phenomenon. Initially it was a government-directed, car-based project, catering for white middle-class families. It has been argued that ‘from the beginning, suburbia was more a state of mind than geographical location’ offering ‘a place of refuge for the problems of race, crime and poverty.’ It provided advantages over the existing city: space, convenience, closeness to nature, (architectural) freedom, and a sense of belonging with like-minded people. It became the ideal home for many and a popular setting for movies and tv series.

However, slowly the dream of suburban life started to crumble. From a Never-Never Land for grown-ups, it became a zone of ‘noir ruination’, criticised and ridiculed by experts (sociologists, financial analysts, designers, environmentalists, planners, etc.) and popular media. The monotonous, dull, almost sadomasochistic environments have become a twilight zone or even more perversely, as J.G. Ballard wrote, ‘the nightmares that wake [their inhabitants] into a more passionate world.’ The lion’s share of suburbia is detached from urban life, enforcing isolation, segregation and obesity. Suburbia is increasingly regarded as an environmental disaster and the physical expression of rotten financial products.

‘Perhaps the suburbs are the only thing left that we can despise’ in terms of architectural taste and lifestyle. But ‘those who argue that suburbia is dying are wrong on the facts.’ Despite a growing critique of suburban culture and a renewed interest in the traditional city at the same time, the suburb is still by far the most desired typology across Europe and the US. And beyond these parts of the world, it is a novelty that is mushrooming and economically thriving everywhere. From China and India to Kenya and Brazil, to live in an American-style detached home with a garden is an appealing – and increasingly attainable – goal for the upwardly mobile. At the same time, there is a remarkable (re)appreciation of existing/older suburbs and suburban new towns. After Brownstones and Brutalism, suburbia is being rediscovered, from Palm Springs to Milton Keynes.

While UN Habitat urges us to ‘regulate and control urban sprawl,’ the same United Nations predicts that the world’s population will reach 11.2 billion around 2100. With cities such as London collapsing under the pressure of their own (refound) success, the triumph of the cities as we like them now might just be a short-lived one. Low fuel prices, improved building techniques, increasing xenophobia and a growing middle class will continue to fuel suburbanisation worldwide.

While the suburbs expand, the lines between urban and suburban are blurring. Not only are the suburbs becoming increasingly urban, being redeveloped into more walkable and mixed-use neighborhoods, but equally, inner cities are suburbanising. They are becoming cleaner, safer and more predictable, in order to pave the way for consumption, tourism and middle-class households. According to Patricia Cober, the 1950s view of suburbs as faceless, homogenous bedroom communities has been replaced with an image of highly differentiated suburban places. ‘They are no longer merely “sub” urbs,’ she argues.

At the same time, we are witnessing the next level of suburban living. The suburb is no longer a quiet refuge away from, but still close to, a particular city. It is becoming a hub in what Keller Easterling calls an inter-urban ‘infrastructure space’. Not only do we float in cars and trains through the suburban networks of the Randstad or the Ruhr, moving from our smart-city homes outside Abu Dhabi (Masdar) and Seoul (Songdo), along the urban corridors of the Pearl River Delta in Southern China and the Taiheiyō Belt in Japan, but we visit the suburbanising traditional historic inner city, or its simulacra in Las Vegas or China, as well.

‘We are all suburbanites’ says Yannis Tzaninis. Suburbia is all around us, there is no escape from it. It has become the norm, with an increasing number of people around the world living sub-urban. Despising the suburb was easy, but now it’s time to take it for what it is: the place many of us call home.