In Egypt, 18 days of protests forced the country’s long-serving president, Hosni Mubarak to resign on the 11th of February 2011. One year later, Egyptians chose Mohamed Morsi as their president, in the first free presidential election in the country’s history. Just over two years later, five activists founded the Tamarod movement to collect signatures against Mohamed Morsi in an attempt to force early presidential elections. The launch of the movement gave the Egyptian military the pretext they needed to topple the new Islamist president, which they duly did in late June 2013.

In response to the military’s seizure of power, Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood supporters organised enormous, on-going sit-ins in Rabaa Al-Adawiya and Nahda Squares to condemn the military coup and demand Morsi’s reinstatement. In mid-August, the security forces dispersed the two large camps within approximately 12 hours, leading to hundreds of deaths and many more wounded.

In this case, questions of urban design intersect with the politics of resistance in important ways. Why, for example, did protesters fail to safely escape the authorities’ violence in Rabaa Al-Adawiya? Would a different urban composition have resulted in a different situation?

The Battle in Rabaa Al-Adawiya Square

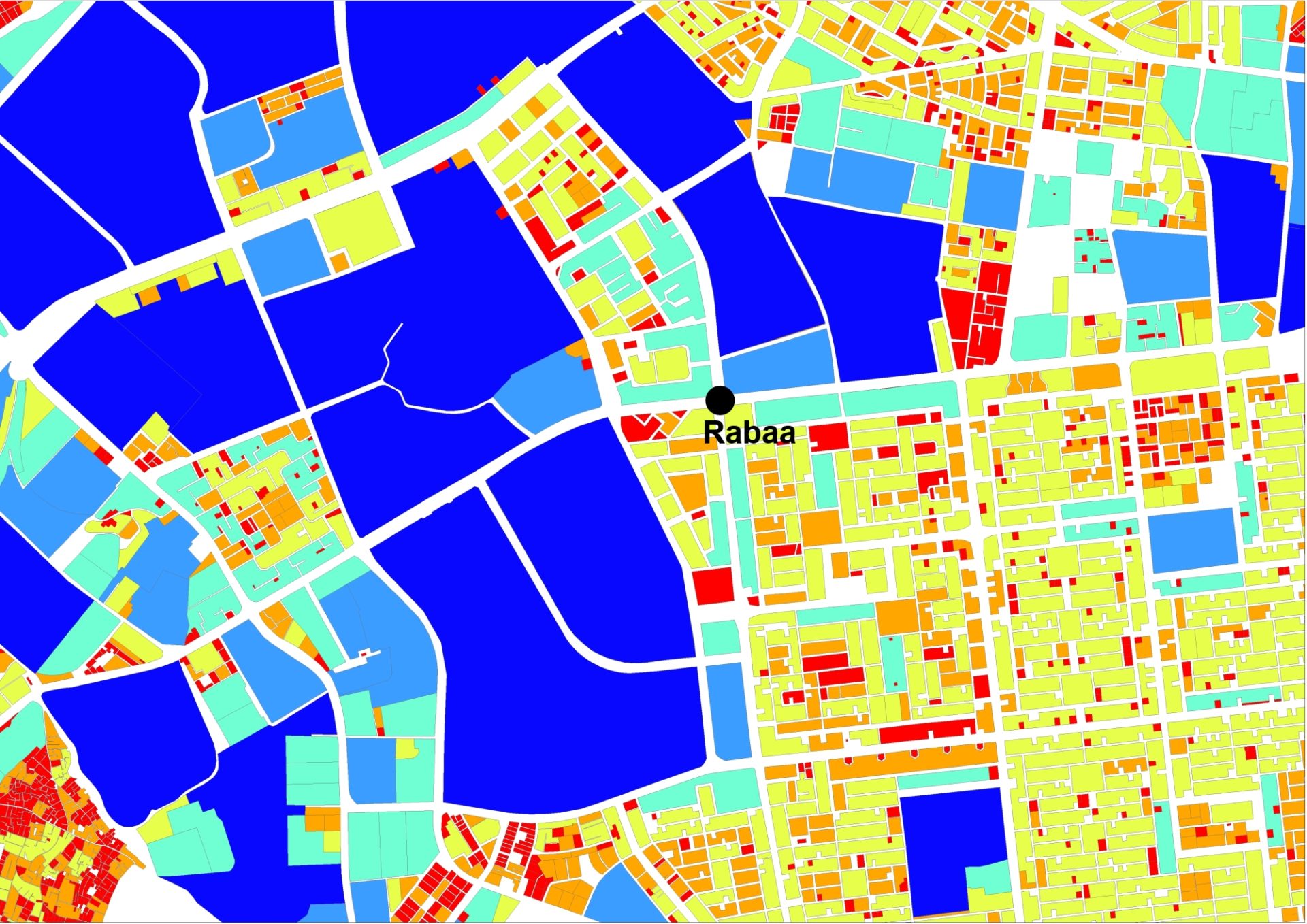

On 28th June 2013, pro-Morsi supporters started building their camps at Rabaa Al-Adawiya Square. Due to huge numbers of protestors, the sit-in expanded around the traffic hub of the two roads intersecting the square: Al-Nasr Street and Al-Tayaran Street. There were five major entrances and checkpoints leading to the camp— two on Al-Nasr Street, two on Al-Tayaran Street, and one on Anwar al-Mufti Street. Demonstrators erected tents along the traffic islands and alongside sidewalks of the two roads. To slow down the movement of the security forces they also built makeshift barricades out of paving stones and other street material. Frequently, helicopters threw threatening papers on protesters asking them to return home; otherwise, the army would disperse them. In response, protesters, expecting a sudden attack, guarded the sit-in entrances with sticks and stones.

On the morning of 14 August 2013, the day of the crackdown, demonstrators awoke to the sound of gunfire coming from the eastern entrance to the square. Thick clouds of tear gas spread throughout the streets. Police, military troops, helicopters, and army snipers deployed on top of buildings besieged the sit-in on four sides and created a no-go buffer zone around the sit-in to isolate the protesters from the surrounding quarters. Police and army cut off aid to the protesters, imposing a strict perimeter around the square so that no one outside the sit-in could join those on the inside and no one on the inside could escape.

After establishing the buffer zone, security forces used armoured bulldozers to destroy the demonstrators’ tents and makeshift barricades. While demonstrators sounded the alarms, police and army personnel, supported by snipers, slowly advanced and attacked the protestors from all sides and left no safe exit. The security forces used live ammunition and rubber bullets on demonstrators who did not get the opportunity to flee. Some protesters remained on the periphery to hinder advancing troops using sticks and Molotov cocktails, while the majority of the protestors retreated to the middle of the square. The square however, like an open stage, offered no place to hide. Over the course of the day, security forces killed hundreds, wounded thousands, and detained huge numbers of pro-Morsi demonstrators.

The Symbolic Value of Nasr City

Nasr City (‘victory city’), the neighbourhood where the protests took place, was formerly a military zone administered by the Ministry of Defence. The new urban quarters were established in the 1960s during President Gamal Abdel-Nasser’s leadership, the first in a line of Egyptian leaders to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood. After the military coup in 1952, Abdel-Nasser aimed at building a socialist country based on the cultural and spiritual values of Arab nationalism. His ideology was built around an anti-colonial trend that manifested itself in the replacement of the symbols of the British occupation with new symbols of Egyptian state power. Nasr City symbolised this new ideology.

The city was planned by the government from 1956-1958 and its on-going construction was subsequently handed over to a private company in 1964. It was supposed to be an administrative centre within the capital and many ministries located in downtown Cairo were to be moved to Nasr City. However, only a few institutions, such as the ministries of economy and defence, actually ended up there. Perhaps the most significant relocation to Nasr City was that of the Al-Azhar University. The urban structure of the area consists of a strict orthogonal grid with large blocks of roughly similar size. The gardens are usually public and maintained by the state. It was in between those large blocks that the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood started their protests in the summer of 2013.

Rabaa Al-Adawyia square in Nasr City was the site of one of two major occupations in Cairo. The location was chosen by the protestors for several reasons. Firstly, to recall memories of the military coup in 1952. Secondly, to challenge Nasr City’s role as a symbol of the military’s influence over society, manifested in such sites as the military parade ground and the tomb of the Unknown Solider on Al-Nasr Road. And thirdly, to protest in the city which has taken for its name the man who initiated the decades-long suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Criteria of a Successful Space of Protest

Asef Bayat, the author of Life as Politics, studied the urban characteristics of ‘Revolution Street’ during the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Bayat identified four ‘socio-spatial’ features of ‘streets of discontent’:

1) centrality — sites where a politicised crowd can swiftly congregate, such as in the vicinity of a university campus, a large mosque or theatre.

2) proximity — sites that have a historical or a symbolic value, ‘either in some inscribed memories’ of demonstrations and contention, or, just due to a proximity to iconic buildings that exemplify state power such as ministries, courts, parliament, etc.

3) accessibility — sites that have access to a transportation (bus, metro) hub.

4) flexibility — sites which are manoeuvrable, where protesters can rapidly escape from security forces, such as spaces that are encircled by narrow alleyways helping demonstrators to disappear.

Rabaa Al-Adawiya square ticks a lot of these boxes. It experiences a high degree of through traffic. It is also adjacent to several sites of historical and symbolic value, such as Al-Azhar University, Cairo Expo Centre, the Cairo International Convention Centre, the Cairo Stadium, the Unknown-Soldier Memorial, and the Rabaa Al-Adawiya mosque. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, it is located in Nasr City, which itself has a vital symbolic significance.

However, it is on the question of flexibility that two aspects severely constrain the square’s usefulness for the purposes of protest. Large urban blocks produce fewer urban islands. While this fosters vehicular movement it has the opposite effect on pedestrian flows. Shorter urban blocks encourage walking by virtue of reducing trip lengths and increasing urban choices. Interestingly, Nasr City has a coarse-grain network of longer blocks. Ministries, military zones, Al-Azhar University, and other public facilities are located on the North-West and are made up of large sectors. They are usually hidden between high gates giving sometimes the impression the city is a series of gated communities. Meanwhile, housing blocks are situated on the South-West and are made up of smaller clusters. Remarkably, the housing blocks located on the outward facing edges of Al-Nasr and Al-Tayaran streets are mostly larger than those located elsewhere. Collectively, the urban layout in Rabaa Al-Adawiya prohibits demonstrators from escaping safely from the security forces.

In other words, Rabaa Al-Adawiya is not flexible. Consequently, police and military troops successfully besieged demonstrators in Rabaa Al-Adawiya by separating them from the surrounding internal street network. To add to this, the protest site was most likely not suitable in terms of the self-protection offered by physical obstacles. The French urban designer Haussmann long ago demonstrated the effect of wide boulevards in neutralising the defensive capabilities of the make-shift barricade.

Unfortunately for the demonstrators in Rabaa Al-Adawiya square, they had no other option than constructing barricades along the wide roads leading to the square. However, these barricades were not very useful in stopping troops, as the wide, long roads allowed for the easy operation of bulldozers and failed to prevent police and military vehicles operating at high speed.

While the Egyptian military, in its breath-taking aggression, should not escape blame for the incredible number of dead and wounded on 13th August 2013, the protest’s outcome can in no small measure be attributed to the urban composition of the surroundings of its chosen site. Centrality, proximity, accessibility and flexibility are crucial features of an effective space of discontent. The protesters’ tragic failure to affect a turnaround of the military coup at Rabaa Al-Adawiya must serve as a reminder of the importance of terrain in the always uneven fight against state violence.