In February 2016, Failed Architecture and the TU Delft Chair of ‘Design as Politics’ co-organised a workshop as part of the ‘Let’s Work!’ graduation studio on the future of work in the city, focusing on Amsterdam’s Vijzelbank building.

The Vijzelbank, designed by the well-known Dutch architect Marius Duintjer, opened in 1973. It was originally built as the headquarters of the ABN-AMRO bank during a period in which the City of Amsterdam’s policies aimed to attract large companies to central locations, known as ‘cityvorming’ in Dutch. The building was a large and modern, and therefore quite rare, addition to Amsterdam’s historic city centre, spurring quite some controversy. Over the past decades, changing political attitudes, economic conditions and cultural preferences have considerably impacted the way we look at ‘work’ in the urban landscape. In 1999, ABN-AMRO was one of the first large companies to move its headquarters to Amsterdam’s new Central Business District ‘de Zuidas’ near the city’s ring road, leaving the Vijzelbank building vacant.

After plans to transform the building into housing failed, it temporarily functioned as an ‘incubator space’ for independent creatives and small companies in the cultural sector. For years, the building thrived with activity, until it was acquired by foreign investors in 2013, who renovated the building according to contemporary standards, and rented it to commercial tenants, displacing the precarious army of creatives to yet another location. Currently, the building is occupied by among others Randstad, a major Dutch multinational specialized in temporary staffing, and Spaces, a new, high-end flexible working concept, where individuals and companies can rent short and long term luxurious office spaces.

Over the years, the Vijzelbank-building has seen diverging manifestations of working in the city, from one, large bank’s Jacques Tati-style rows of cubicles to ultra-flexible hang-outs that look more like hipsterfied coffee bars rather than actual offices. For the workshop, which took place in various locations in the Vijzelbank, students were challenged to extrapolate current trends in work, employment and urbanism in order to envision future scenarios for the building. This resulted in three remarkable, slightly dystopian proposals, warning us of the direction in which urban and labour conditions could be heading.

Work As Leisure | Leisure As Work

The first group of students (Federico Riches and Martin Dennemark) took the fact that the average working hours in the Netherlands are slowly decreasing as a starting point, speculating on a future in which the boundaries between leisure and work have become blurred. Inspired by business models like Facebook or Google, in which consumers become ‘prosumers’, and who, by using free products and services generate valuable data – they imagined a future in which the ubiquity of smart objects allows us to become ‘productive’ while travelling, experiencing and enjoying life.

In their future scenario most work has been automated and some humans work by generating data through leisure activities. They imagined the Vijzelbank as becoming a place of temporary employment for people who struggle to find work, because their skills have become obsolete. Instead of applying for unemployment support, people can come to the building and earn money through a series of leisure activities. Upon agreement, subjects are monitored throughout different leisure activities and their sensorial reactions are transformed into valuable data. The Vijzelbank would house all sorts of leisure functions such as bars, restaurants, shops, a movie theatre, a fitness club, a training centre and nightclubs. The building becomes a testing ground for companies, where they can try out new products and services, getting to know detailed responses by end users.

Prins & Keizer – Where Work, Care And Education Come Together.

The second group of students (Ludo Groen and Matiss Groskaufmanis) imagined the future of the Vijzelbank building as a place where by offering workspaces with additional health care services, senior and elderly people can remain active on the labour market. Their concept responds to the expectation that the Dutch state pension age will increase to 71.5 years by 2060, while at the same time 50+ employees have a higher risk of long‐term unemployment and socio‐economic marginalization.

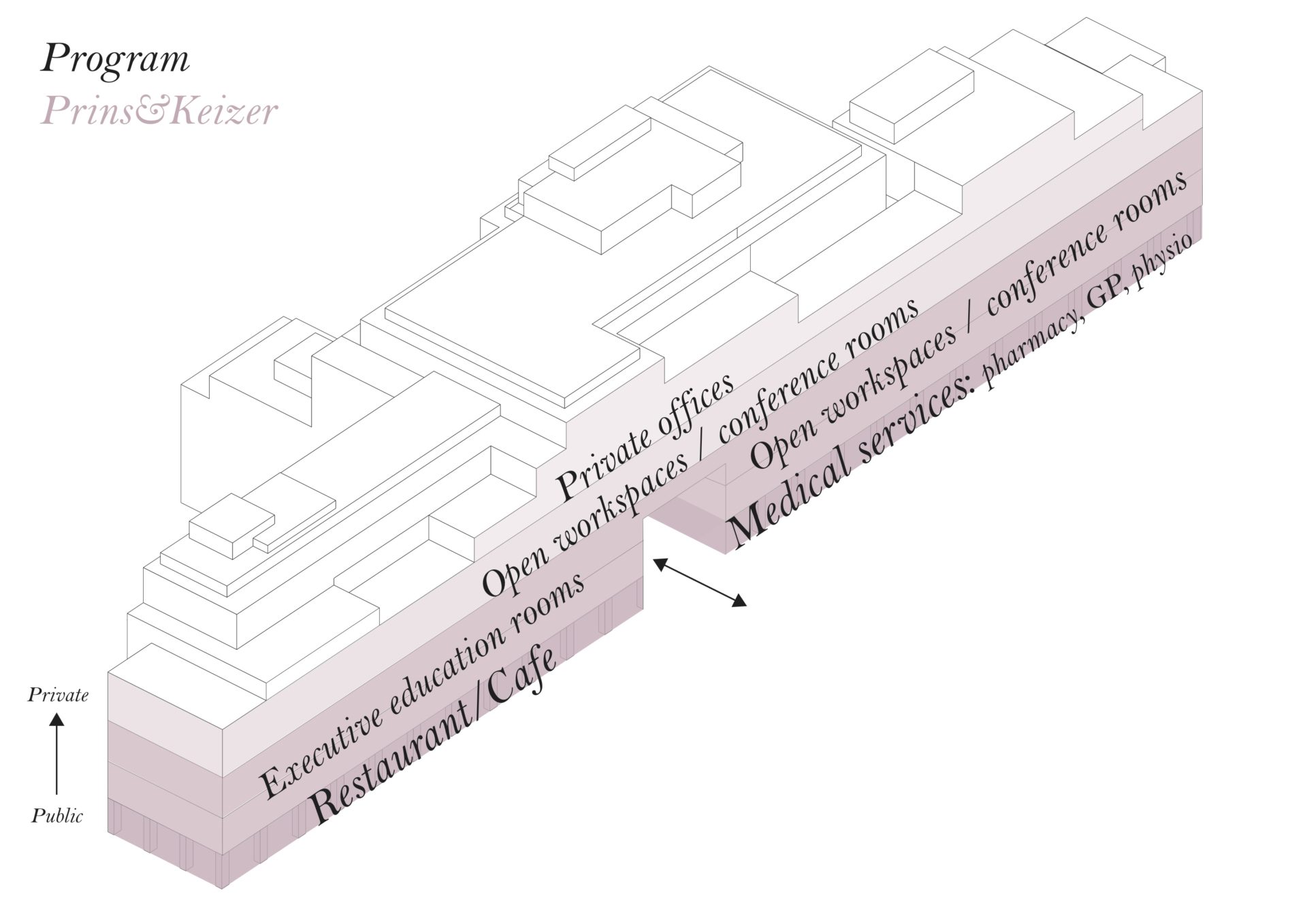

The ageing population will significantly affect the employment market, as the post‐war ‘baby boom’ generation will go into retirement, putting pressure on state social budgets, while generating an immense demand for healthcare and insurance industries. At the same time, the Netherlands has the highest volume of accumulated pension funds in Europe, worth up to 160 percent of the GDP. Based on these developments, it is proposed to join forces with one of the mayor Dutch pension funds and to convert the building into ‘Prins & Keizer’, a work and healthcare centre for the elderly. The building would accommodate flexible workspaces, meeting rooms, a business mentoring department, a wellness centre, and an array of medical services and social programs.

Working Everywhere: The Intensification Of The Inner City

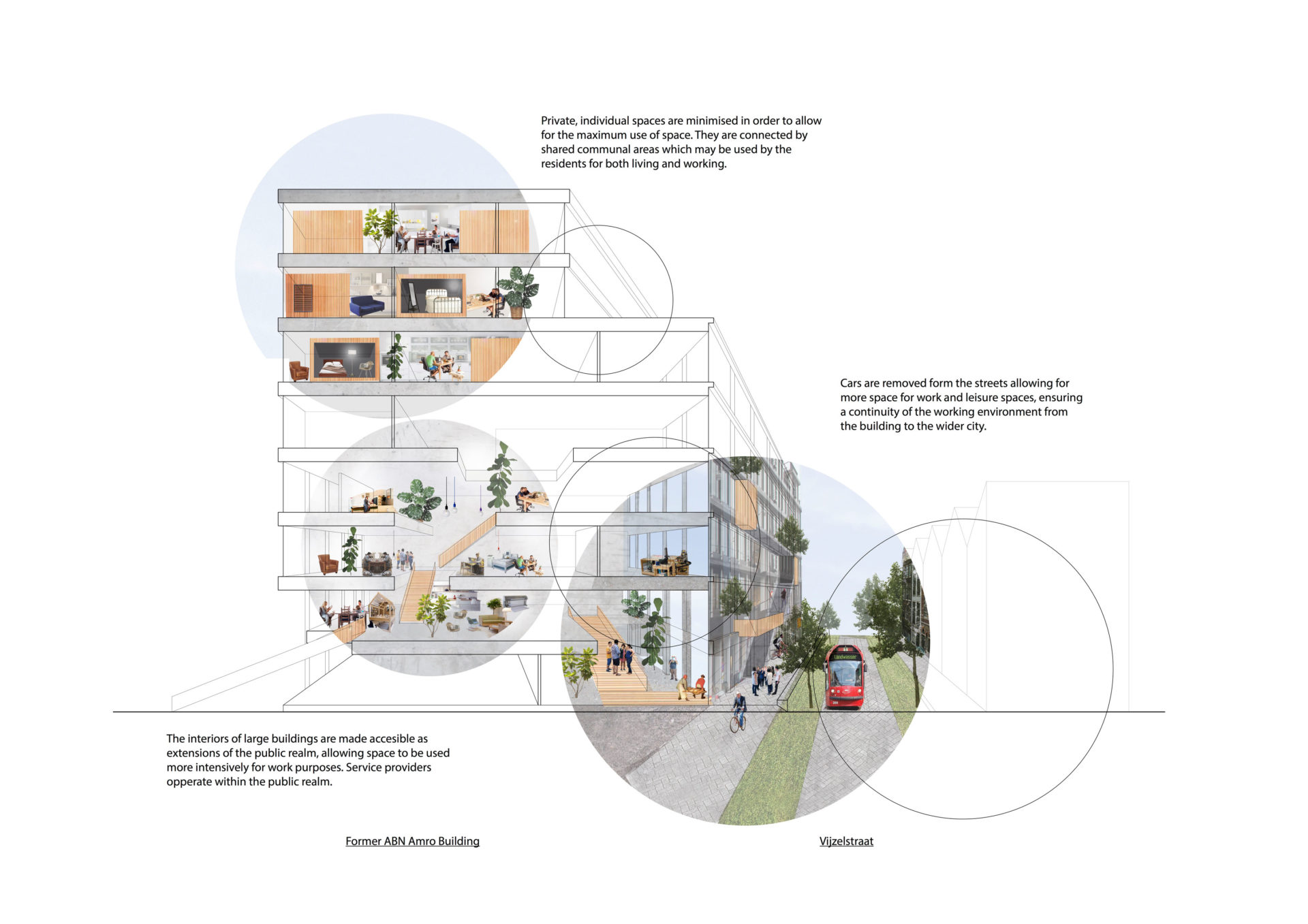

The last group (Wyn Jones, Zuzanna Mielczarek and Gintarė Norkūnaite) extrapolates the fact that the city is increasingly seen as a popular location for small, young companies, many of which desire to remain in the city centre as they grow. Their proposal responds to a future in which the centre of Amsterdam has gone through an immense population boom, with a significantly increased amount of people occupying the historical city centre for work, leisure and living. In order to keep rental prices affordable, they propose a new type of working space in which facilities such as administration, catering and specialist production are decentralized and shared by various organizations on demand. This will not only result in decreased costs, but will also have spatial implications.