‘Welcome to the Next Economy. Let us show you a world where regret and frustration are a thing of the past; a world where as a premium member you are assured of a brighter future’, thus begins a narrative voice a tour of the smart, controlled and segregated city featured in the VR installation at the entrance of the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016. While we extrapolated this techno-dystopia into a comprehensive, dark urban future in our previous article, this year’s IABR promises an alternative urban future under the theme of ‘The Next Economy’. After quickly browsing the terrifically staged exhibition, the catalogue and the extensive programme, it becomes readily apparent that the IABR doesn’t present a visitor with a clear manifesto, set of directions or strictly-defined policy advice. Instead, a narrative of ‘inclusive, healthy, sustainable and productive’ cities is presented, with the key characteristics of this ‘Next Economy’ hidden in the subtext of the collective presentation of projects, texts and talks. From the large amounts of visual and textual project presentations a visitor will encounter, we have traced several anchor points of this ‘Next Economy’s urban future.

Go Local

A core mantra of IABR–2016 is the need for an urban economy in which value is added on the local level instead of simply being extracted from it. This means that ideally, economic activity generates value for people and business in the locality, rather than for the shareholders of large corporations who are generally located elsewhere and have no local interests. The Afrikaanderwijk Cooperative (which just as IABR–2016 is located in Rotterdam South) is an example of a project that re-localises cash flows, connecting local manufacturers, spaces, businesses, skilled residents, and the local market. The project encourages people and businesses to spend locally, consequently strengthening the area’s weak economy. The cooperative also provides services for this year’s IABR, for instance by cleaning the venue. Another way to create an economy that channels capital into a certain locality is to induce large market players to invest in local projects. Atelier Utrecht, one of IABR’s multiple-years research-by-design projects, focuses on the relationship between health and urban development. In addition to providing advice for sound urban environments, it asks a simple but crucial question: why don’t health insurance companies, if they invest so much in real estate projects (generic housing for the most part) invest more in building projects that actually contribute to healthier environments, something which directly influences their core business? Or take the Dashilar Hutong regeneration project, which by coupling the local population to planners and designers aims to have current residents benefit from urban renewal, instead of being pushed out by gentrification.

The People Stepping In

From elderly care and social housing to neighbourhood centers and libraries, many local services are rapidly losing their government funding. While some may survive on a more limited budget, many of the facilities once provided by the state will be forced to close down. In some cases the market can step in to fill the gap with privatized facilities, but it will not do so when there is no prospect of making a profit. In the ‘Next Economy’ the people end up filling this void themselves, by re-creating these facilities through collaborative projects or even establishing facilities that no state would ever have provided. Collectives in the Swiss capital of Bern are transforming a former waste incinerator into ‘a compact, mixed, ecological, communal residential and commercial neighbourhood’, providing low-cost housing and facilities in a generally exclusive city. Locals in Brussels created a shared garden and community center on a removed train emplacement, thus connecting various neighbourhoods and generating social cohesion without governmental steering. And some of Beijing’s thousands of underground air raid shelter inhabitants are establishing collectives to improve their living conditions and create communal spaces while they are waiting for more formal housing arrangements.

New Coalitions

When neither the market, the government nor a group of local inhabitants wants to deliver certain services on their own, there is another solution that is clearly evident in the ‘Next Economy’. Many of the projects are characterised by the innovative way different stakeholders are collectively working on spatial interventions. While public private partnerships, involving both a government and market parties, have been common for some time, it appears as if the field of spatial production will see more daring collaborations in the future. In Port Harcourt, local residents, lawyers, urban designers, architects and filmmakers are collectively campaigning against the destruction of a neighborhood, both through legal battles as well as by providing an alternative urban plan. In Antwerp, the municipality has invited multiple design teams to engage with real estate owners, users and inhabitants to draft proposals for infill developments in the 20th century urban ring, which are much needed in a city whose population is growing rapidly. The IABR itself presents a new model for collaborative spatial practice by the aforementioned ‘ateliers’, where different stakeholders are brought to the table to rethink pressing issues outside the regular planning arena.

Public Space Is Key

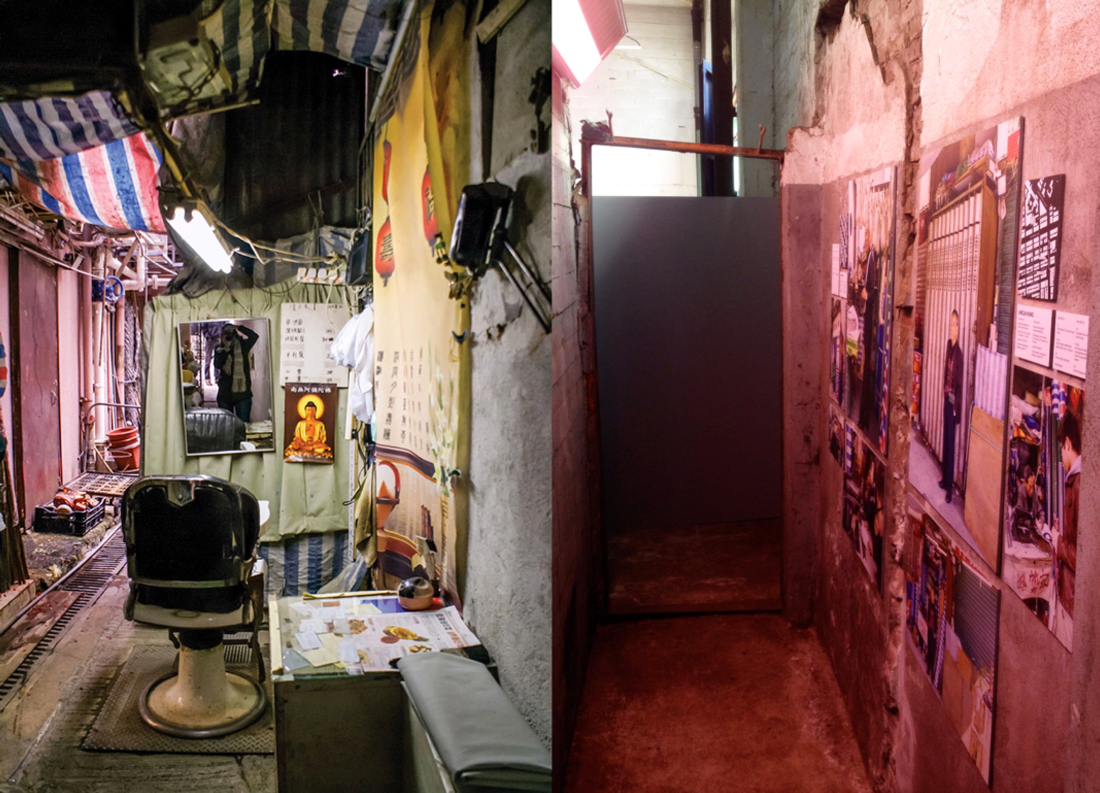

A strong public domain is crucial to ensuring that the city of the future is ‘inclusive, resilient and agile’, according to the curatorial statement. It should embody spaces of encounter, diversity and difference that everybody can use, that are complex and incomplete and that trigger creativity and trust. Many of the exhibited projects show the importance of the various uses and high levels of publicness of urban space. Hong Kong In-Between explores the informal developments in Hong Kong’s porous network of alleys which at different times offer room for gathering, entrepreneurial activity and the extension of private space, thus providing numerous opportunities for the city’s many migrants. The 1,000 families living on Manila’s cemetery show another way that public space can meet (unintended) demands, when no other forms of regular housing are available. In Barcelona, a decentralising, distributed economy demonstrates that shared resources and collective facilities are important parts of the public domain, enabling residents to take charge of their own lives through projects that aim to make the city self-sufficient by 2050. A possibly more controversial piece at IABR–2016 is the City of Toronto’s promotion of the development of ‘privately owned, publicly accessible spaces’ (POPS) for the King-Spadina neighbourhood.

Mix Those Functions

Modernism’s strict mantra of functional division has long been abandoned by most planners, who nowadays increasingly prefer to mix residential, commercial and leisure facilities as much as possible. While this process of bringing different, basic functions together is often projected on the neighborhood scale, the ‘Next Economy’ foresees more radical blending and even the return of industrial production to the city. In Amsterdam, it is proposed to transfer the classrooms of vocational schools from the large, isolated and peripherally located educational buildings to relevant locations in society, from airports and clubs to churches and warehouses, providing students with real-life experiences. In Haikou (China), a projected park is not just a green space designed to spend a leisurely afternoon, but has been planned to host educational and research facilities and to purify the river water at the same time. Another IABR atelier, focusing on Brussels, has explored how a paradigm shift from the post-industrial to the productive city can lure small scale industrial activities back into the urban landscape, contributing to both social cohesion and the local economy.

Energy In Transition

A good part of the Biennale imagines the urban future to be more green and energy-efficient and shows how this could be (or is already being) done, from the acupunctural to the continental scale. The giant infographic video installation 2050 – An Energetic Odyssey shows that we should not underestimate the challenge, but that – with an entrepreneurial government – the North Sea could provide for almost all the energy required in its surrounding countries using 25,000 wind turbines. Other projects show how energy transition can have a positive local impact. The iShack Project in Stellenbosch (South Africa), is a social enterprise providing informal settlement dwellers with solar panels that generate enough electricity for a small TV, a cellphone charger and three lamps. Unhealthy and dangerous kerosene lamps are replaced by clean and safe electricity, while the change has a positive impact on their disposable income. Atelier Groningen explores how the move to clean energy can positively impact the urban and rural landscape while improving economic opportunities, by, for instance, turning a large biochemical complex into a hub for the biobased economy. An important element of the bottom-up project Hackable Cityplot in Amsterdam, which features housing, workspace and cultural facilities, is the concomitant de-polluting of a former industrial site during its development.

With this quickscan of projects, trajectories and themes, we hope to provide an insight into the extensive collection of ideas and ideals presented at IABR–2016. Through the projects on show, most of them simultaneously touching on several issues, the biennale presents some possible directions for the future of the city. While these directions are clearly normative and will most likely spur further useful discussion in the coming weeks, the biennale simultaneously invites its visitors to take a position themselves. It urges architects, urbanists, citizens and other spatial practitioners to formulate their own idea of where they would like to see developments advance, to determine landmarks on the distant horizon to which they would like the world to proceed. By moving beyond a focus on the design of things and opening up the debate about the actual society of the urban future, the IABR is not your average architecture biennale. In our upcoming coverage of IABR–2016 we will delve into these debates and critically examine the Next Economy’s central ideas. As the ever accurate cliché goes: architecture is never not political.

This article was produced as part of Mark Minkjan and René Boer’s position as ‘critics-in-residence’ during the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016.