Envisioned as a comprehensive urban renewal project, Kompleks Tun Abdul Razak (Komtar) in George Town, Malaysia has had a troubled history. Part slum clearance, part town hall, the complex was intended to provide a ‘New Urban Centre’ away from the colonial-era civic district. With a landmark office tower over a commercial podium, series of residential blocks, and a geodesic dome inspired by Buckminster Fuller, Komtar was to be a flagship example of modernist planning.

Instead, the building has ended up as a monument to the failures of modernism. Plagued by fire during construction, left incomplete, and gradually abandoned by commercial tenants, Komtar is now largely seen as an eyesore by locals and visitors alike. Yet despite these setbacks, Komtar endures with an incredible stubbornness. Beneath the tower that houses government offices, migrant workers have colonised the warren of commercial spaces, creating a lively transnational space. New multi-million ringgit plans to augment the main tower with external elevators and a rooftop restaurant promise to inject new life to the precinct. It remains to be seen whether these plans will revive the ailing complex, however, or if Komtar’s neoliberalisation will be yet another bumpy chapter in the building’s story.

Like a modernist campanile, Komtar is the landmark by which people in George Town orientate themselves. For decades, it was the only skyscraper of note on Penang Island, sailing over the terracotta roofs of the historic city below. The tower was envisioned as the crowning glory of a ‘New Urban Centre’, and for a moment, it seemed like this dream might be realised. When the main tower topped out, Komtar was among the tallest buildings in Asia.

At the driving of the first pile on 1 January 1974, then Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak made clear what the project symbolised:

“This project would change the face of the city, discarding the colonial heritage image in favour of one which reflects the identity of Malaysia and its multi-ethnic culture.”

The tower was Penang’s belated answer to the modernist statement pieces built to mark Malaysia’s independence in 1957. Like those buildings in Kuala Lumpur – including the Parliament, National Mosque, and Stadium – Komtar was meant to express a new Malaysian identity, rejecting the historicist styles of the colonial past; onion domes and pointed arches gave way to curtain walls and concrete brise-soleils.

First proposed in 1962, the project only truly got off the ground in 1970. The organisation set up to oversee the design of Komtar and a number of parallel urban renewal projects was headed by Lim Chong Keat, brother of the island’s Chief Minister. It drafted a masterplan for the city a number of years before the nation had even gazetted its Town and Country Planning Act. The plans involved the first proposals to conserve the old centre of George Town as a heritage site, while developing the area between Prangin, Maxwell, Penang and Magazine Roads into the ‘Penang New Urban Centre’.

In its design, Komtar has a fine modernist pedigree. From its separation of functions to the unapologetic, functionalist aesthetics of the entire precinct, the original masterplan was a virtuoso performance in mid-century design.

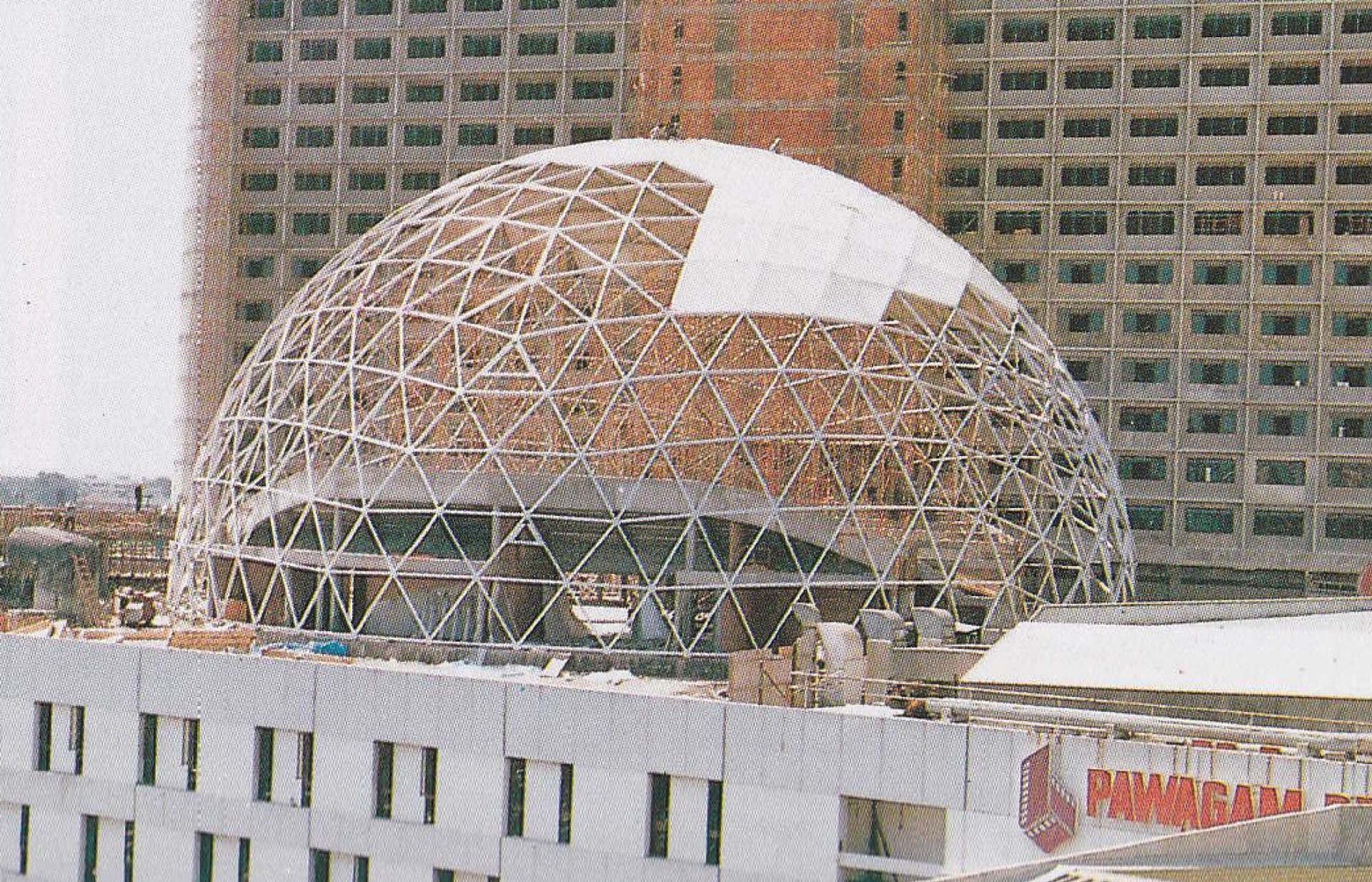

The entire complex would occupy an eleven hectare site situated between four major roads. Rising from a four-storey commercial podium, three 17-storey residential blocks were planned to replace the nineteenth-century neighbourhood that had been cleared for the project. As noted by Dr Gwynn Jenkins in her book Contested Space, these were to provide a ‘socially-engineered residential community’ in flats of mixed income and ethnicity. The 65-storey central tower would house government functions and offices. The geodesic dome – testament to the strong influence of Lim Chong Keat’s friend and colleague Buckminster Fuller – would house the Dewan Tunku function hall. Public transport and multi-storey parking facilities would make this the hub of George Town. Komtar was an entire civic and business district condensed into a single complex. The building promised George Towners a quality of life unimaginable in the rapidly decaying nineteenth-century shophouses that comprised the majority of the city’s housing stock.

As of 2016 however, almost half a century since its conception, only two of the complex’s five phases have been completed, and millions of ringgit are being poured into redevelopment in an attempt to revitalise the complex. So what went wrong?

Early on in the building’s construction, costs blew out. The building’s foundations seemed to be absorbing vast quantities of concrete and cash. Further delays were caused by a fire which broke out in the upper storeys of the construction site on 23 January 1983. When Phases 1 and 2 were finally completed, the budget had blown out from RM200 million to a staggering RM300 million.

Once the four-storey podium, dome, and 65-storey tower were finished, the masterplan was abandoned. In place of three residential towers, a single luxury hotel was built. Instead of providing new, modern homes for the residents who had been cleared for the project, Komtar ended up displacing some 3,175 residents, plus numerous petty traders and small businesses. Instead of raising revenue for the state, the project had become a financial liability. The leases for the construction of the remaining phases were subsequently sold to private developers. The main tower remained empty until government offices moved in. Even before the ribbons had been cut, Komtar was beginning to look like a white elephant.

Without a local community to keep shops afloat, Komtar’s commercial spaces were perhaps doomed to failure. Today, the mall in the podium is in an advanced state of decay. Long forsaken by shopkeepers, many of the lots remain shuttered. Through the 80s and 90s, a series of failed department stores served as anchor tenants. By 2008, some 40% of Komtar’s traders had left the building. The building’s layout may be partly to blame. An eccentric floorplan of criss-crossing indoor lanes make it difficult to navigate what is, in fact, a rather small area. Many view these dark, empty spaces as dangerous, and middle-class Penangites have long eschewed Komtar for more fashionable shopping malls along Gurney Drive or to the island’s south. In this regard, the suburbanisation of George Town’s population has not helped Komtar. Newer shopping centres in the vicinity, including Penang Times Square and First Avenue, have also made the building look shabby by comparison.

The extent of Komtar’s decay was recently highlighted by a fire which broke out in the abandoned theatre on the podium’s third floor. The event was later blamed on ‘vagrants’ allegedly living in the theatre.

Yet Komtar’s shopping centre is not completely empty. The shops that do remain cater, by and large, to the city’s migrant labour force. Hailing mostly from Myanmar, the Philippines, and Bangladesh, this ethnic make-up is reflected in the services provided by the shops – and in their signage. Convenience stores that stock Filipino snacks, phone shops with international sim cards for calling Bangladesh, Burmese eateries that give migrant workers a taste of home in plates of crunchy lahpet – this is Komtar today. Despite their precarious, marginalised position in Malaysian society, these migrant workers have carved out a transnational space for themselves in the very heart of George Town. In contrast to the general commercial failure of Komtar, the spaces colonised by migrant workers are busy, even thriving.

How long such spaces last is another matter. The State Government intends to gentrify the area, and has courted private money to achieve this. Some RM40 million has been pledgedto refurbish levels 5, 59, 60, 64 and 65. New retail spaces are planned, but the most ostentatious part of the proposed refurbishment are a pair of external ‘bubble’ elevators leading to a viewing platform and ‘sky lounge’ on the two topmost storeys. The redevelopment is intended to attract tourists as well as business investment, and save the ailing mall.

If attempts to rehabilitate Komtar succeed, they will become part of a broader trend in George Town. The city’s UNESCO World Heritage Site – immediately adjacent to Komtar – has already undergone a drastic wave of tourism-driven gentrification. The once decaying port city now boasts one of the region’s most high-profile arts festivals. Art galleries, boutique hotels, and cafes constitute the ABCs of this new George Town. But the city’s gentrification has come at a cost, and long-time residents and heritage activists alike have been involved in a protracted battle against mass evictions.

The repeal of rent control in 2000, followed by the city’s inscription to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2008 were a lethal combination for George Town’s housing affordability. The worst affected have been the city’s elderly, turned out after a lifetime of enjoying controlled rents. If Komtar’s gentrification is successful, it is likely that the entrepreneurial migrants who run small businesses there will suffer a similar fate. For the second time in its history, Komtar may displace a number of small businesses in attempt to ‘modernise’ the city.

Eyesore or icon, Komtar has come to represent George Town. Its transformation will be a barometer of the direction the city takes in the early twenty-first century. Across the historic centre, homes have made way for spaces of consumption, and old traders have given way to new businesses. The reinvention of Komtar’s main tower, with the seat of local government crowned by a rooftop restaurant, may well be an apt metaphor for the neoliberal city George Town is becoming.