While using online platforms, we are generally served up information suggested by algorithms that is based on traces of our previous searches, conversations, purchases and locations. A simple example: “hey, you might want to follow ArchDaily on Twitter, since you already follow Dezeen.”

The result is a “filter bubble”: we rarely encounter anything that is outside our comfort zone, we only engage with people who share our worldview and we often end up simply being sold more stuff that we already have, all the while making sure that our behaviour fits the image that we want others to have of us. Different search results for different people make for cultural and intellectual isolation.

Bryant Park, New York.

Image: kyle rw/Flickr.

Public spaces in cities risk a similar destiny. Cities are becoming archipelagos of fragmented and isolated islands, separating different groups of people. The more wealthy parts are increasingly designed to death for reasons of security, efficiency and retail, while CCTV, police, private guards and mobile phone tracking systems keep a close eye on us. Because we don’t want to get in trouble or simply don’t have time for it, we all police ourselves and try to behave like middle class consumers. Limited in their diversity of people and functions, and closely controlled, public spaces increasingly minimise the potential for unexpected encounters and limit the range of possible uses.

A new public domain

Healthy public spaces are crucial for a robust society. Maarten Hajer, Chief Curator of International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016, calls for a new public domain as a fundament for the Next Economy, to improve inclusivity, sustainability and productivity. “It should be a public domain that can be, and in fact is used by a diversity of groups, and where difference and diversity have positive connotations.”

“Take the London Tube”, says Hajer, “it’s a great place to observe subcultures, and to see trends change. It’s a shared experience that wouldn’t exist if everyone was in their car.” The inclusivity of the Tube can be contested however, with fares twice as high as in other major cities. Hajer sees Chicago’s Millennium Park as another good example: “It attracts many tourists – with visitors numbers similar to the Eiffel Tower – but locals also go there. When the weather is hot, black kids from the surrounding areas play in the fountains. This is the kind of public domain I am talking about.”

And it’s not only about social quality. Hajer extends his ideas about public space to places for learning and doing business. A good public domain, he argues, provides good “innovation milieus”, which “essentially depend on the same dynamics. Big corporations, the ‘elephants’, now realise they need to communicate with start ups, the ‘mice’.” But their natural habitats are too corporate, which makes it “unlikely that they will engage with these startups”. This type of innovation, Hajer says, is essentially dependent on the urban interaction that is characteristic of good public spaces. He adds: “inspiration and new ideas do not necessarily come from officially-staged meetings. It is much more about ‘encounters’, here or there, in milieus that are diverse and can surprise and intrigue.”

Surprise is also central to sociologist Richard Sennett’s ideal type of urbanity, encompassed in his term ‘porosity’. Porous places are incomplete, open to unscripted actions and unplanned functions. They evolve over time. Sponge-like, they can absorb diversity and provide opportunities for people to gather, do business or just hang about. For Sennett, Delhi’s Nehru Place, an intense, socially mixed and complex market is a dream example.

IABR–2016 has several projects on show which revolve around public space. Flex Test ROC proposes to re-introduce vocational education to Amsterdam’s inner-city, in unconventional typologies that interact with other urban cultures, including schooling ‘to-go’ at train stations and flexible setups in underused buildings. It sounds like Hajer’s ‘innovation milieus’. The project Hong Kong In-Between highlights the vital public space in Hong Kong’s 150-km-long alley network, where micro businesses provide basic necessities, specialised goods and services, and employment opportunities for many of the city’s immigrants. This micro network, just as with Sennett’s Nehru Place, is highly flexible and adaptive. The celebrated dynamic in both places is also largely informal, context-specific and unplanned, which makes them impossible to duplicate. Moreover, such places are vulnerable, not least to real estate logic and ‘regeneration’. The challenge here is to preserve urban porosity, but how can you preserve something that is necessarily in flux?

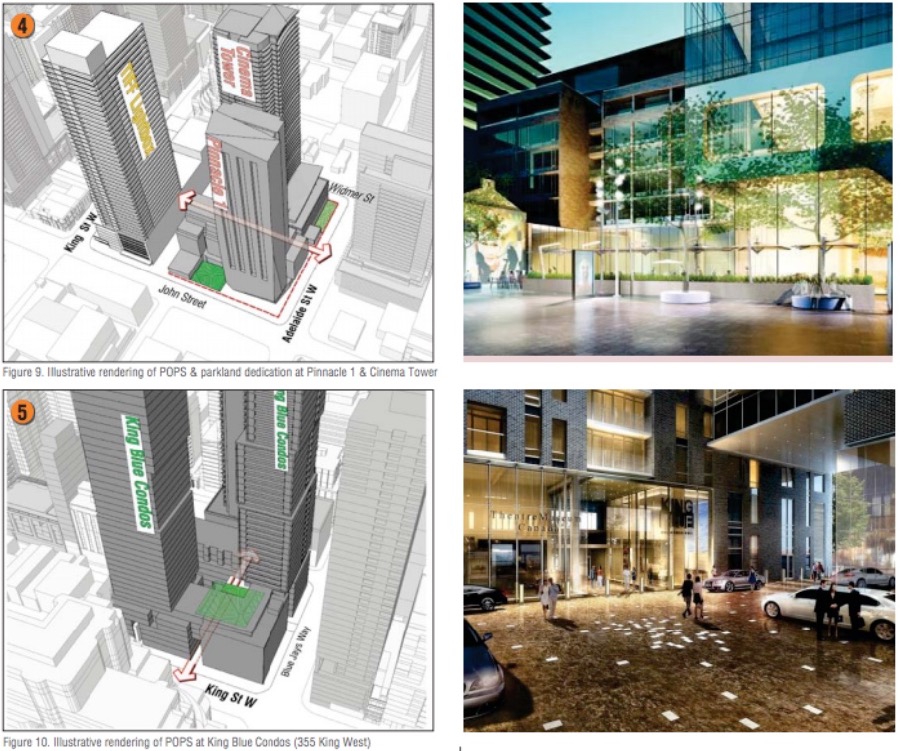

Toronto pops

Another project in the exhibition that stands out – albeit not because it represents the most inspiring urban future – is Toronto’s King-Spadina neighbourhood, an area characterised by enormous real estate development pressure. At IABR–2016 the City of Toronto shows its struggle with developers who lie in wait, ready to fill every possible rent gap in the area, driving out affordable office space, housing, and cultural venues. Densely built King-Spadina has limited public space. The solution the City of Toronto presents is to seduce real estate companies to create privately owned publicly-accessible spaces, or “POPS” in spatial code. The urban design guidelines document is cheerfully subtitled “Creative placemaking to enhance urban life”, but doesn’t incorporate existing criticism towards the use of POPS. While the document shows how developers and property owners can create courtyards, plazas, landscaped setbacks and other places on their property for people to take a break from the fast life in this successful part of town, it refrains from discussing who cities are for.

“I’m ambivalent about Toronto’s approach,” says Hajer, who included the project in the biennale to show the planning dilemmas that emerge in economically successful cities. “I can see where it comes from. But perhaps it would have been better to initiate a fund, to finance the creation and maintenance of public parks and squares, which developers can contribute to.” He doesn’t see the slivers of space adjacent to or underneath these properties becoming a desired kind of public realm: “Developers won’t necessarily have the motivation to do the right thing, to attract all kinds of people. They would regard this as a security risk. The situation in Toronto shows the increasingly limited clout of local governments to force or incentivise developers to do it right.”

The problems with privatised public space

“If you have control over who is on your property, that’s not public space,” says Bradley Garrett, human geographer at Southampton University. Garrett is also author of the book Explore Everything: Place-Hacking the City, and writes about POPS for the Guardian. Living in London, where public space is sold off to private companies at an increasing pace, he sees that POPS limit the potential range of activities in the city, because they set restrictions for their users. In many open spaces in London, private security guards keep watch because there are so many things you are not allowed to do: amongst other things photograph, congregate or protest (property owners are free to create any kind of limitation).

So what about Toronto’s ‘creative placemaking’ using POPS? Garrett: “In London, they try to make the same argument: if it wasn’t for the POPS, there wouldn’t be any public space. We have to ask the question what happens when pieces of the city are being given away, chunk by chunk. It starts to blur the line between what is a privately owned public space and a publicly owned public space. It’s a small step from there to saying ‘why don’t we just have private companies manage the parks and other public spaces because look how well this is working.’”

Garrett thinks the main problem with POPS isn’t ownership, but the management and control of the spaces. “It’s not public space, because the space is for some of the public, some of the time, and those rights can be withdrawn at any time.” He argues that there should be legislative changes that say that such places have to be governed by the law of the land and not by the will of the property developer.

All alone on the AstroTurf®. Granary Square, London.

Alexander Edward/Flickr

POPS are often places of consumption, whether they are malls, plazas in front of residential towers or squares such as London’s new Granary Square. Garrett looks at POPS in the broader context of cities, which are “increasingly only built for flow – flows of people, of finances – everything has to keep moving. In the neoliberal model of flow, stasis is a threat. Someone staying still, people in one place, that is concerning. Someone having a sandwich, okay, but man, if they take a nap we’ve got a serious problem!”

Hajer sees it differently. “It’s the same argument that [architect and writer] Michael Sorkin uses: if homeless people aren’t allowed in, it’s unjust. But does that always have to be the case?” He agrees with Garrett’s argument for having the same rules for actual public space apply to POPS.

Indeed, ownership doesn’t have to be the defining element. New York’s Bryant Park is generally celebrated as a success story of a crime ridden space that turned into one of the “most popular parks in the US”. In fact, it is publicly owned and privately managed, by a local Business Improvement District. Large parts of the park are often taken up by events with admission fees, and it caters for a certain crowd. Bryant Park is not the most preferred type of public domain for Hajer because it shows a strong middle class bias: “it’s not that you’re forced to consume in Bryant Park, but you have to fit certain behavioural norms. Having a beer wrapped in a brown paper bag [brown-bagging is nicely explained in The Wire] doesn’t fit into this social code, but having prosecco at your kid’s birthday party is perfectly fine.”

15 years ago, Hajer and sociologist Arnold Reijndorp published the book In Search of New Public Domain, in which they concluded that a well-functioning public domain can also exist in privately owned spaces of consumption: “we found that certain food courts in shopping malls did meet the diversity and encounters that we see as crucial to a healthy public domain. Think of Georg Simmel’s Brücke und Tür [Bridge and Door], in which he describes places where things naturally converge. This doesn’t always have to be public territory in the traditional sense.”

Testing the publicness of urban space

Garrett continues to oppose London’s privatisation. He founded the London Space Academy, which has a two-step battle plan. “First, it maps all of the public spaces in London and then codes them according to activities that can take place there. What this also does is that it raises awareness about what you can’t do in these spaces, because often that’s invisible.” The second step is testing spaces through Space Probes: interventions with which the security apparatus of urban spaces is tested and a community is built that “can mobilise to build a commons or at the least undertake placemaking.” The first of these space-reclaiming interventions recently took place in front of London’s City Hall. The open space is privately owned by a Kuwaiti property company since 2013, which means that you can’t protest in front of the city’s seat of government anymore.

Garrett: “Ideally I would like a flood of people to go to Granary Square and tell the security guards to get bent. If they want to call the police and have the riot police remove everyone from privately owned public space – great, they should do that, that would be fantastic.” The approach is reminiscent of Provo. The 1960s counter movement provoked violent responses from authorities in Amsterdam using playful actions and interventions, in order to draw attention to their radical message. Following violent crackdowns, Provo mobilised public opinion and Holland’s hippy era took off. Will the current fight for urban space also gain momentum?

Back to urbanity

We know that the commons will not make a comeback soon. But however spaces are owned, we can’t have exclusive private or political interests dictating public life. And we can’t let business sell us illusionary ideals of safety and order. Spaces that are for some of the public, for some of the time, are spatial filter bubbles: suburbanized, monocultural parts of the city devoid of urbanity. Real cities have lots of open places where people can casually meet, exchange, freely express themselves and develop a sense of belonging. Spaces where otherness is encountered and where non-consumers are also citizens. The task ahead for those designing and running cities in the Next Economy is to cultivate diversity and serendipity, and permanently trash the idea that everything can be designed and controlled.

And designers aren’t unaware of this. Two weeks ago, the New Yorker ran a profile on landscape architect Adriaan Geuze of West 8, who recently completed the landscaping of a new park on Governors Island in New York (and was curator of IABR–2005). Geuze says: “There’s no doubt that mass culture has a hundred-per-cent success in making the world programmed. Everything is branded, everything has a name, has a function that you have paid for. That makes a very relevant question for our generation of designers. [..] Maybe we should make an environment where everyone can enjoy the lightness, and you can play.”

This article was produced as part of Mark Minkjan and René Boer’s position as ‘critics-in-residence’ during the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016.