Global developments have resulted in increasing numbers of people arriving in Amsterdam over the last few years. Conflicts in the Middle East, in particular Syria, and worsening conditions in some African countries have brought about an unprecedented exodus of refugees. In the last three years millions of people have come to Europe risking their lives by braving the Aegean and Mediterranean seas in small boats. A small percentage, but still a considerable number, of survivors, chose Amsterdam as their final destination.

At the same time has the rise of affordable travel, the growing wealth of a global elite and the meticulously crafted brand of I amsterdam led to rapidly increasing numbers of tourists coming to Amsterdam, from all corners of the world. All these refugees, tourists, and other ‘guests’ come with a certain image of Amsterdam in mind, and spend considerable sums on their travels. Ironically, refugees often pay considerably more for their dangerous, one-way voyage, in many cases all they have. Amsterdam has subsequently received and accommodated her new guests in strongly diverging ways. Their status – their financial means still available and obviously nationality – has been the decisive factor in the kind and amount of hospitality granted to them by the city.

Those with the right passport and some financial back-up are allowed to roam around freely. Their money, thanks to the market economy, an eager real estate sector and few legal restrictions, directly translates into the provision of space for the facilities they demand: ‘travel like a local‘ Airbnb-apartments, ‘experience world class‘ hotel chains, welcoming ‘expatcenters‘, ‘for people in the creative industries‘ international private member clubs, ‘not-for-tourists‘ all-inclusive short stay hotels, ‘iconic‘ department stores, and numerous museums, restaurants, souvenir shops and rent-a-bikes, all located in or nearby Amsterdam’s overly protected UNESCO world heritage ‘historical urban ensemble‘.

Those without the right ‘papers’ and with less money in their pockets are limited to a different set of spaces, their availability and access often erratic and arbitrary. Some will be allowed into a temporary emergency shelter within Amsterdam’s perimeters, or something similar in a hidden location far away from the city. A small but lucky number might, after obtaining their papers, even be provided with affordable housing. Those denied their papers will end up roaming the streets of the city however, always on the lookout for the police, and might sleep with friends, in the city’s refugee squats or on the streets. When they do encounter the police, they might be incarcerated for an extended stay in ‘foreign detention’, for example in Amsterdam’s new airport migrant jail.

The large number of spaces allocated to, or occupied by, Amsterdam’s ‘guests’ can be seen as several dynamic but separate architectural archipelagos in the city. While they are internally very well connected – hotels list popular tourist attractions, refugees inform each other about shelter options – they are usually disconnected from their urban context and each other. The spatial demands of these archipelagos sometimes even conflicts with the city’s own need for space; permits for new hotel rooms continue to be issued while a shortage of student rooms remains a problem. As these different architectural archipelagos of hospitality evolve quickly over time and move around the city, they occasionally end up in a space which was in use by another ‘type of hospitality’ just before. The sudden repurposing of a space belonging to one archipelago by another not only reveals the stark differences between different regimes of hospitality – in terms of power, liberties, aesthetics, vocabularies – but also their many similarities.

Over the last year, architect and photographer Nina Kopp and Failed Architecture’s René Boer have been in an ongoing conversation about these ‘architectures of hospitality’ in Amsterdam. They were in particular intrigued by the sudden transformations happening as a result of these replacements, in which a certain space, inhabited by a specific type of the city’s ‘guests’, was quickly and quite easily converted into a space fitting with another type of ‘guests’. Recently, Kopp and Boer started to document two particular case studies containing such a transformation from one ‘archipelago of hospitality’ to another, by contrasting collected statements from the initial situation with photographs and promotional material from the following situation. As all the city’s guests set off to Amsterdam with the hope to fulfill certain objectives, it makes the inequality of opportunity the city provides all the more disturbing.

‘Australa & Borealis’ > ‘premium hospitality with a cause’

“On the ‘bajesboot’ a minimum of four men share

one prison cell. You are supposed to collaborate

with your extradition to your home country and

not to enjoy your time on board. You share your

prison cell with people from different countries.

Or they arrange it like this: three from one

country together with someone from another

country, speaking a different language.”

Unfortunately, due to the lay-out of the hotel,

we do not have any family rooms nor inter-

connecting rooms available.

“I was brought to a tiny prison cell, which I had to

share with six others. I felt like a cockroach, or a

rat. We were not treated like humans. I had no

privacy at all, not even on the toilet.”

With us, it’s about being able to be YOU!

“In Regime A the cell doors are opened from

8am to 12am, allowing for a bit of walking,

reading or chatting. At 12, the doors are closed

and food is brought to the cells.”

Just so you can explore the city the way you feel like

“The detainees are allowed less time out of their

cells or in the courtyard. Budget cuts, leaving

less money for guards, are the apparent reason.”

The best things in life are free. WiFi. Everywhere.

Enabling our guests and members to discover

the destination like a local and do good at

the same time.

“The Immigration Office creates a dossier for

every detainee on the boat. I was shocked to find

out that they made detailed reports from phone

calls I made and guards collected information

about me, among others details that could have

only been provided by my cell mates.”

Freelance workaholics, foodies, live bands, world

travellers, adventurers, magazine-maniacs, and

true Amsterdammers – they all gather here.

“There are two telephones in the recreation area.

For sixty men. There is a lot of noise, and a long

queue. People are fighting constantly. Don’t call

too long, so many people are waiting after you.

Calling your loved ones is everything but private.”

No golden taps or mahogany desks but a bed

you want to take home, crunchy croissants, great

cappuccino’s and the most genuine service you

can imagine.

The ‘bajesboten’, or ‘jail boats’, as the two floating detention centers were known, were installed in a harbour area between Amsterdam and Zaandam in 2007. The boats were constructed to detain ‘illegalised’ asylum seekers, whose applications were rejected. In theory, the boats were their last call before extradition by plane, but in practice many of its detainees were impossible to extradite and released without papers or a place to go. Over the years, the ‘bajesboten’ were closed having built up a dubious reputation, as, according to various human rights organisations, life on board was harsh and desperate. In 2015, one of the boats underwent an internal upgrade, during which the cells were transformed into modest hotel rooms. In summer, it was towed to a premium location close to Amsterdam’s central station and opened to a (paying) public as ‘The Good Hotel’. This new hospitality concept has prided itself for being a ‘social enterprise’, offering training opportunities to ’70 long-term unemployed locals’. Recently, the boat has been transferred to a permanent position in London.

‘We Are Here’ > ‘Right Here, Right Now’

“We are here, we can’t go back to our home

countries, we can’t go to another country and we

are not allowed to stay here. We ask for a normal

life. We want that policies here in the

Netherlands and in Amsterdam gives us, and all

other refugees on the streets or without reason in

jails, the possibility for a human existence.”

It’s up to you. Do you want to climb in or dive in?

“This week someone brought in some beds

found in the bulk waste nearby. Beds from an

actual bed store, nothing wrong with them, and

much needed for the women here.”

The bed was amazingly comfy – we just didn’t

want to get up!

“The industrial hall in central Amsterdam is called

‘Vluchtmarkt’. It was occupied on a Sunday

afternoon in early April, as several female

refugees had nowhere to go and other places

where already full.”

A place where the comfort of a hotel merges with

the feeling of belonging to a community

“This space is now for sale for €800,000 or for

rent for €6500 per month. So far they haven’t

found anybody able to afford these amounts. The

owner communicated in a letter that they want

the inhabitants to leave within a week.”

Aimed for generation Y travellers that are all

about a digital life-style. They are connected 24/7

and are comfortable in a world filled with touch

screens and quick service.

“All buildings are in dire need of a serious

renovation as basic facilities are still lacking. ‘We

Are Here’ and its supporters are transforming

these empty buildings into inhabitable

accommodation. Because of the enormous

amount of work this poses, and materials and

financial support needed.”

Socializing is nice, but even better after a hot

shower. Our bathrooms are luxurious, clean and

separate for men and women.

“I am having fun with my friends as I am cutting

vegetables and prepare the dough in the big hall

where we’ve installed the kitchen. Sometimes

somebody knocks on the big door; a lot of people

from the neighborhood are bringing supplies. The

atmosphere is exceptionally good while there are

so many different nationalities present.”

Stay in your own hub with a huge bed. Re-

charge yourself. And your phone.

“People left, very sad, their nice new home, that

they turned from a ruin into a beautiful place,

where they felt happy and safe and had open

house every Wednesday evening, with food,

falafel and ping-pong. The refugees thank the

neighbourhood and the people from the market

in front of their house for the wonderful time.”

The feeling of belonging to a community, not to

mention the convenience of a hostel.

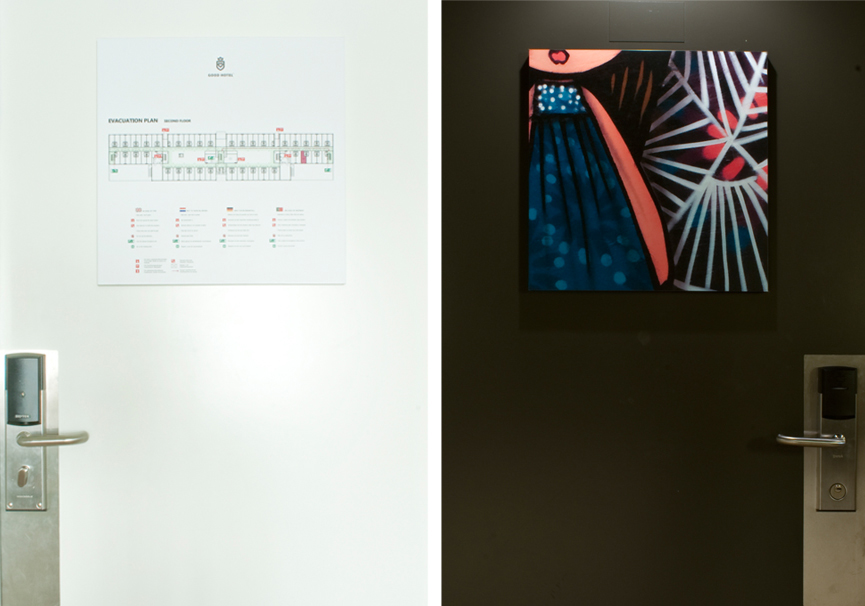

De Vluchtmarkt was a group buildings near the Ten Kate market in Amsterdam-West, all of them squatted in March 2014 by tens of illegalised refugees of the ‘We Are Here’ collective. ‘We Are Here’ has over the last few years continuously squatted buildings to both house themselves and to draw attention to their precarious situation. From the first day of the occupation, the group has worked continuously to transform the dilapidated buildings into proper accommodation, among others for its women’s group, and collective spaces. By the summer of that year, the Vluchtmarkt was evicted by the authorities. Soon after, the main space of the former Vluchtmarkt was rented to some young entrepreneurs working on a new hospitality concept. In fall 2015, they launched ‘Cityhub’, consisting of 60 ‘hubs’, or lockable micro-cabins containing a double bed and some space to stand. The hubs, featuring wifi and air-conditioning, are stacked on top of each other in pairs and are made from simple, clickable materials. The hubs can be booked on Cityhub’s website, prices determined by an algorithm.

Amsterdam’s Architecture of Hospitality is a research project by Nina Kopp and René Boer. All photographs by Nina Kopp. The quotes related to the Bajesboot and Vluchtmarkt have been selected from various online witness statements and press releases. The written promotion material related to The Good Hotel and Cityhub has been selected from their respective websites.