It has been hard to miss the relentless PR campaign that has been ‘co-living’ this year – one we’re told will solve the housing crisis in London and recently evangelized by Patrik Schumacher at the World Architecture Festival in Berlin. For those missing the fanfare, co-living is the housing equivalent of co-working, aimed at solvent, yet asset poor, young professionals. It rests on a premise that Generation Y’ers are predominantly single, want flexibility, convenience, and value authentic ‘experiences’ over material possessions.

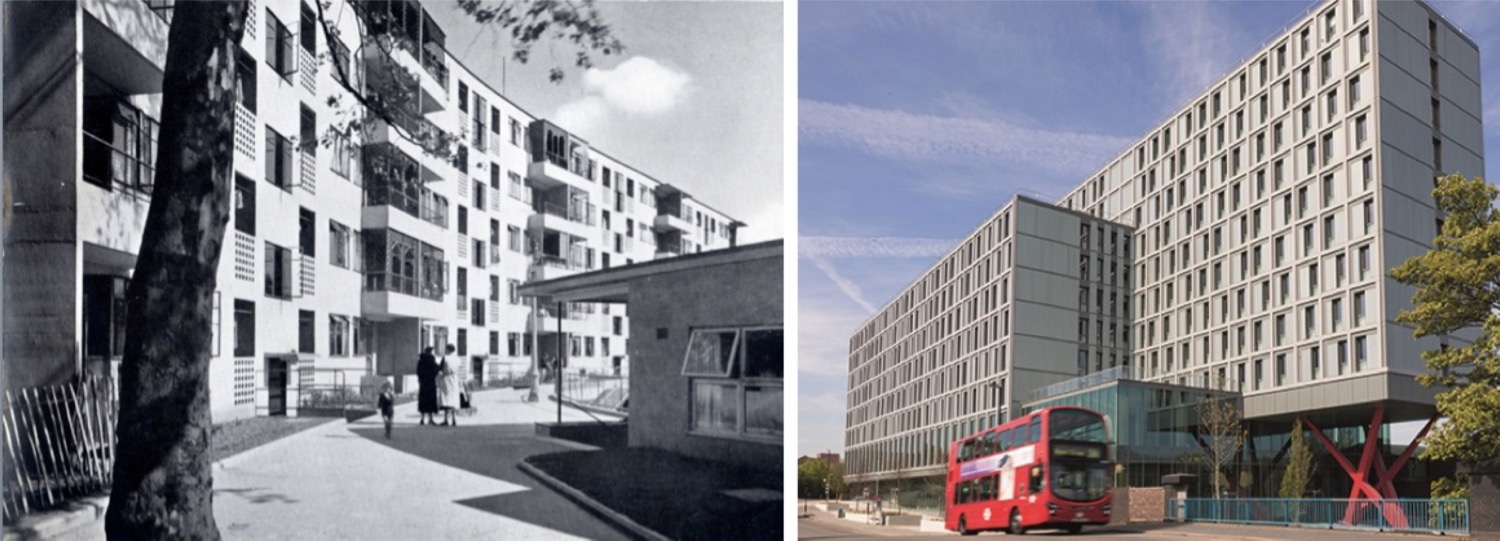

Spatially, this plays out with an emphasis on communal spaces – the kitchen, living room – at the expense of private space, seen as a mere place to sleep. At its most elaborate, the communal space can include a plethora of restaurants, tearoom, bars, work spaces, laundries, roof terraces, fitness rooms and building apps to book events. And it’s a concept that’s gaining traction. Co-living, as this latest and marketable housing mode, now exists in many of our major cities; typically those with acute housing shortages. The first to dramatically scale this up – and self proclaimed co-living pioneers – have been developers The Collective Partners LLP with their The Collective Old Oak in Willesden, North West London. A self-contained behemoth, The Collective Old Oak hosts 400 co-working spaces and 546 bedrooms, varying from studios to standard en-suites, at an average cost starting £1040 per month.

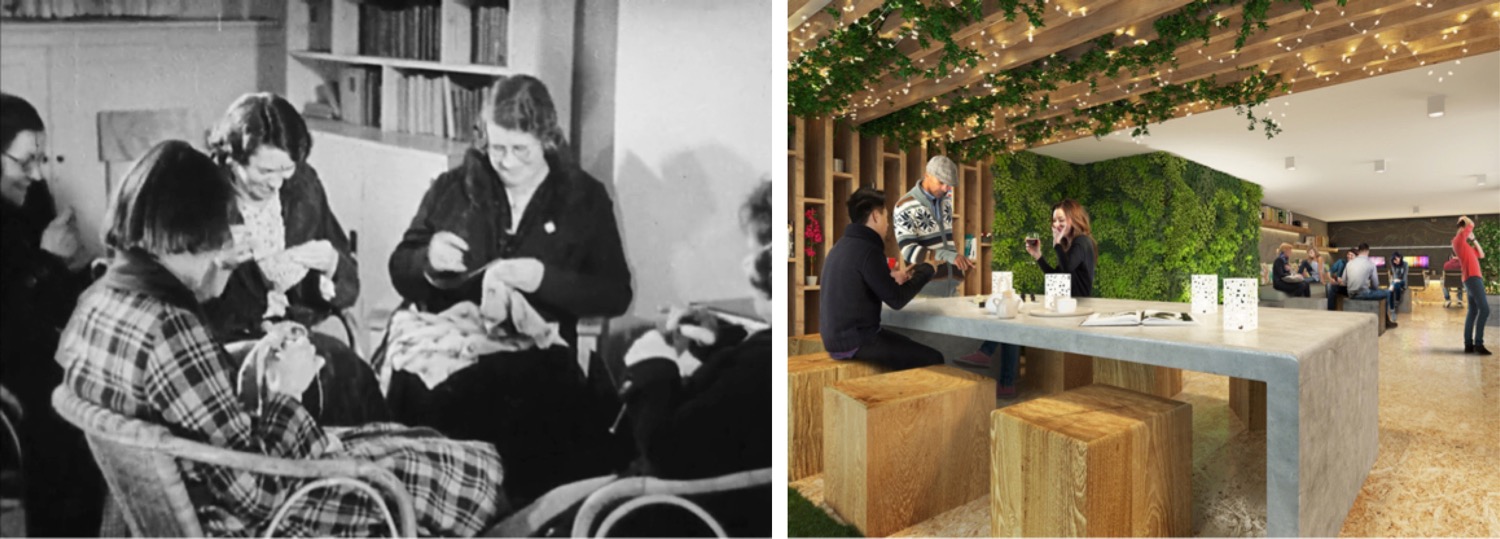

Yet it’s the 930m2 of communal space that apparently separate it from high-end student halls or generic luxury flats in the city. Here, young residents can enjoy “shared kitchens and lounges on every floor, communal entertainment spaces and luxury facilities including a gym, spa, cinema room, library, restaurant, bar, curated retail outlets, events spaces, roof terraces and more.” At Collective Old Oak you don’t live in an apartment block but a “curated community” – the catchall term curation used to describe how residents are chosen to the multiple events aimed at connecting people. These can range from mindfulness and meditation to networking events, business talks, workshops, film nights and live music.

Read together, the price, exclusivity, substandard size of bedrooms and cynical view of community have been rightly highlighted as criticisms of the building. The most alarming feature of The Collective Old Oak though isn’t the banality of its architecture, the vague claims of solving a housing shortage or the pessimistic idea of a narcissistic youth driven through the next networking opportunity. The most alarming feature is this “new way of living”, is in fact a commodified old way of living; one that is steeped in the language of modernism yet robbed of its radical social intent.

CEO of The Collective, Reza Merchant’s, claims of a youth being “far more willing to invest in experiences versus material possessions” or the building’s description as “a way of living focused on a genuine sense of community, using shared spaces and facilities to create a more convenient and fulfilling lifestyle” could easily be used to describe British inter-war experiments in modernism. In fact, the parallels between ‘The Collective Old Oak’ and inter-war modernist pioneer, Wells Coates ‘Isokon’ – or Lawn Road – in north London are striking.

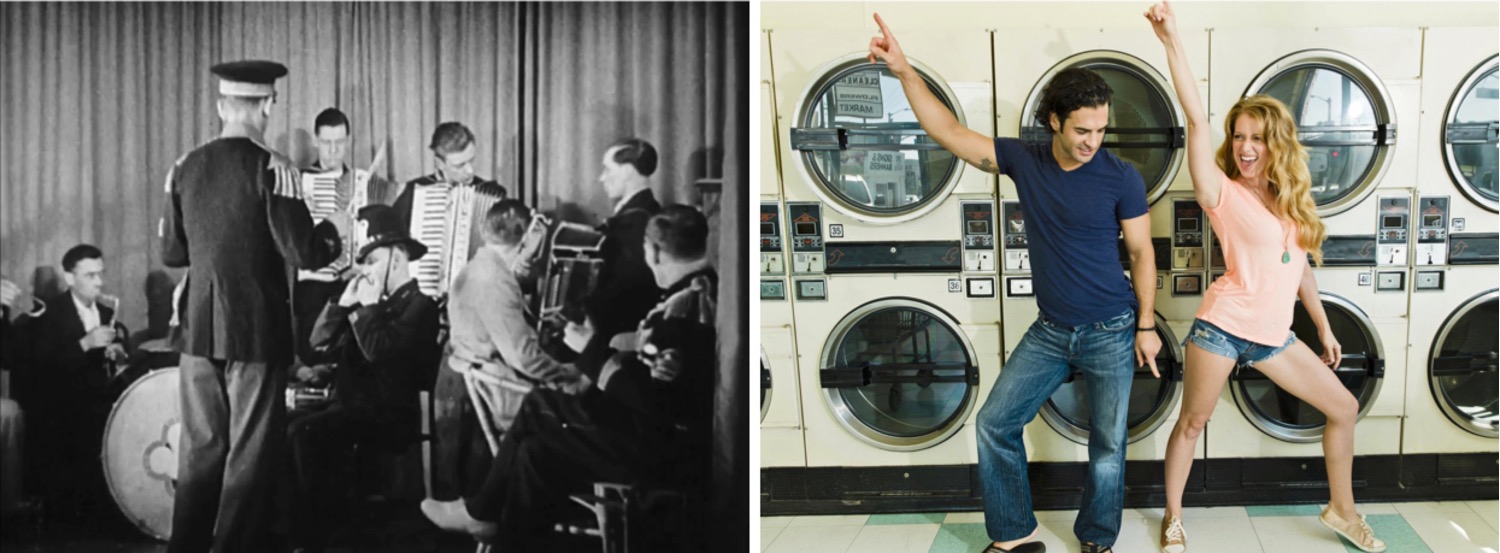

Built between 1933-1934, Isokon was designed as a form of shared living that moved beyond the nuclear family, heavily indebted to Le Corbusier’s ‘Vers une Architecture’. It featured 36 affordable apartments for young professionals that came fully furnished to encourage a minimalist lifestyle with a range of services available: from shoe-shining and cleaning; to bed-making and meal delivery from an on-site kitchen. Coates, in describing this avant-garde ethos explained “We cannot burden ourselves with permanent tangible possessions as well as with our new possessions of freedom, travel and experience”. A building to live and work, Isokon offered a communal laundry, roof garden and the infamous restaurant ‘Isobar’. The clientele of Isokon, during its early history, were the unashamed intelligentsia and emigres of the era; the claims of an egalitarian, communal living somewhat incongruous with the exclusivity of the building.

Isokon, however, should not be seen in isolation. This experiment was part of a wider programme during the inter-war period by the Modern Architectural Research Group, or MARS, to advance modernist discourse within Britain. Initiated by Coates – but by no means defined by him – MARS was the British offshoot of CIAM that would work “sometimes as a purely architectural cohort, and sometimes in league with other likeminded reformers,” seeking “to convert governments to the merits of modernism as a solution to contemporary problems.”

The method of this conversion was through built and unbuilt projects, with a sustained ‘propaganda’ campaign using journals, exhibitions, film, radio, lectures and that would take modernism from a peripheral discourse to subsequent post-war dominance. Underlying this was a social agenda that held civic value above monetary motives; a belief that a decent standard of life should be available to all through healthcare, housing and work reforms; that all this could be achieved through planning the future.

Another such example that took the ideas of Isokon but demonstrated an ability to merge the political, social and aesthetic was Kensal House, built in 1937 as the first modernist housing estate in Britain. A collaboration between Maxwell Fry, a founding member of MARS, and the prominent social reformer Elizabeth Denby, Kensal House radically deviated from the brief – set by the Gas Light and Coke Company – to cheaply house ‘slum dwellers’ while showcasing gas technology.

It did so through a scheme Fry would dub an “urban village”: two self-contained structures that provided 2 to 3 bedroom apartments with balcony gardens and a heady mix of community facilities and services. The long list of communal facilities included: workshops, a communal laundry, nursery, community centre, allotments, clubroom and canteen facilities. Residents could join the Feathers Club, attending sewing, metalwork and woodwork classes or borrow a book from the buildings library. They could get supper and tea from the communal canteen while listening to their own resident band or socialise with neighbours playing darts and other games. On top of this, Kensal House was run as a genuine collective that made decisions on the everyday upkeep of communal areas and allotments, in describing this ethos, Denby elaborates “the spirit of the estate is that the people run it themselves”. The self-management of the estate and amenities included had far wider reaches. This was in particular for housewives who, as Elizabeth Darling describes in ‘Negotiating Domesticity: Spatial Productions of Gender in Modern Architecture’ were liberated “from time-consuming housework” and able to participate in a democratic decision making process.

Both Isokon and Kensal House, as examples under a wider MARS discourse, were instrumental as experiments showing the potential for modernism to solve mass housing needs, through a rethink of what housing is and can be. The discourse was against – and developed as a reaction to – the laissez faire city where housing was commodified, deregulated and market dominated; leading to the situation of housing crisis as normality. Kensal House, in particular, would become a prototype for the architecture of the welfare state and subsequent post-war modernism. While this has been criticised for an elitist, formalist and top-down approach; the idea of housing as a universal right should be rightly praised.

Seen in this historical context, The Collective Old Oak and wider co-living developments, mark a worrying shift where not only does neoliberal urbanism erode the last remnants of the welfare state – in the form of council housing sell offs and redevelopments – it further hijacks and monetizes the very ideas traditionally in resistance to unfettered development. And let’s be clear, The Collective LLP aren’t aligned with a wider movement of social reformers, they’re aligned with investors who want a return on capital. This return is clearly fruitful – The Collective LLP with PLP Architecture look set to gain planning permission for a larger self-contained development in East London, scaling up their “innovative form of rental accommodation” to 30 storeys. With it, an aptly regressive housing strategy sold as progressive continues.