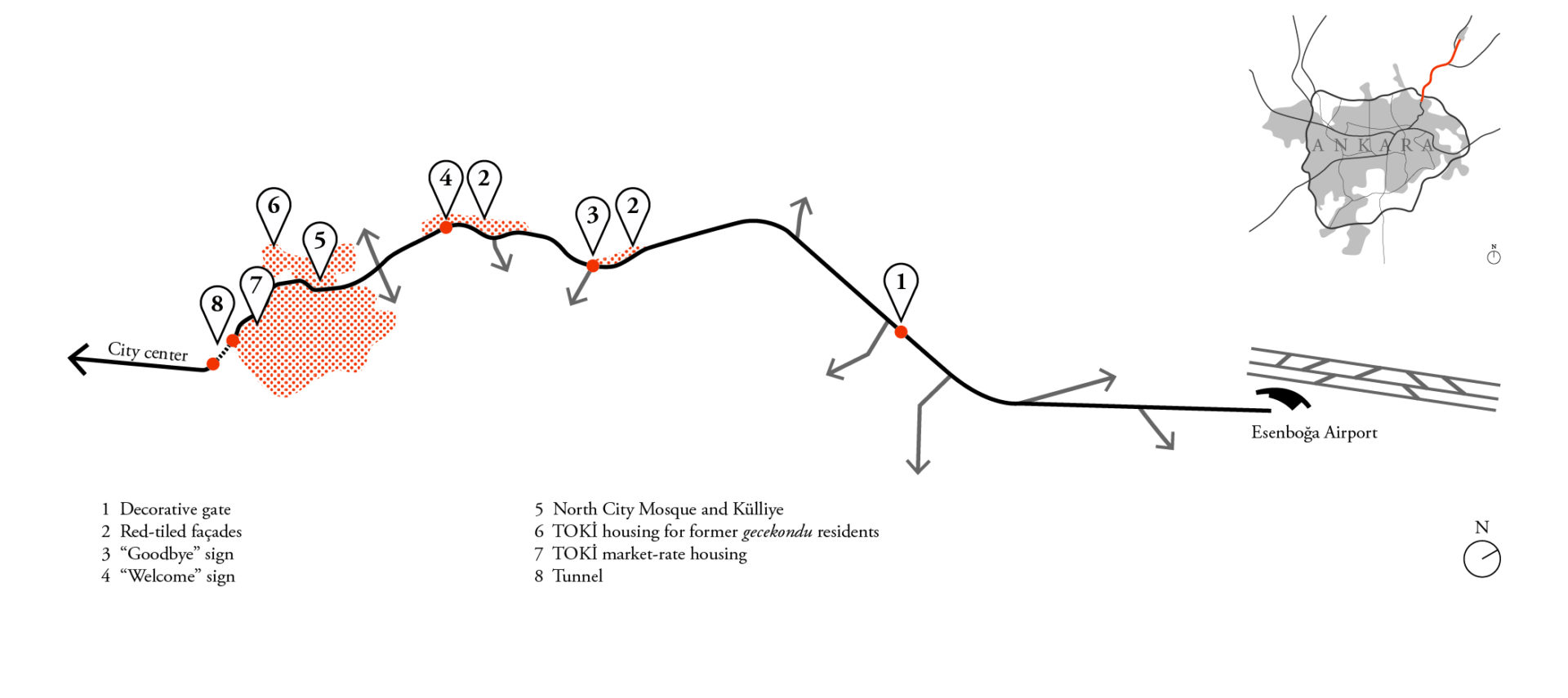

As the capital of Turkey, Ankara welcomes tens of thousands of political leaders and diplomats from around the world each year, weighting its airport road with symbolic importance as it shapes dignitaries’ first impressions of both the city and the country. However, driving along this 17-kilometer highway, also known as Protocol Road, from Esenboğa Airport toward the city center, visitors encounter a chaotic sequence of architectural imagery that fails to present a coherent identity. The government has recently choreographed a series of architectural and urban interventions intended to portray Ankara as a global city rooted in an ancient past, yet these uncoordinated insertions present an overly self-conscious image, disconnected from its surrounding physical and social contexts. These projects loosely fall into two categories: those that evoke a continuum with a storied past and those that simply aim to beautify the capital.

Since coming to power in 2002, the conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) has increasingly eschewed the Republic’s founding secular ideology in favor of glorifying Turkey’s Islamic past. Among many other examples, this preference has manifested itself architecturally in a decorative gate constructed over the airport highway. The mayor stated that upon seeing the gate, visitors will grasp the overall aesthetic quality of the rest of the city, even before seeing Ankara proper. There are five of them, each between 56 and 68 meters wide and between 25 and 30 meters tall, constructed over each major highway into the capital. Although composed of a steel structure spanning eight lanes of traffic on only three posts, its architectural detailing reflects Ottoman and Seljuk traditions via domes, arched windows, and turquoise-colored tiles.

Setting aside questions of the appropriateness of employing historical ornament, the chosen elements misrepresent Turkey’s Islamic past. The construction of monumental standalone gates derives from the tradition of triumphal arches found in non-Muslim empires and is foreign to Ottoman or Seljuk contexts. Furthermore, the proportions of the domes are closer to onion domes rather than those found in classical Ottoman or Seljuk architecture. More important than the gate’s inaccurate reference to local history or the character of the contemporary city is the missed opportunity it represents to more wisely spend five million Turkish liras to improve the lives of residents living nearby.

Occupying a 65,000-square-meter area along Protocol Road, the North City Mosque and Külliye is another project that aims to revive the Ottomans’ triumphant past. The term külliye describes a mixed-use typology commonly deployed in the Ottoman Empire from the thirteenth to the eighteen century that contains public amenities, usually a library, soup kitchen, bazaar, bath, and madrasa, surrounding a central landmark, in this case a mosque. Government officials involved with the complex were explicit that they aimed to bring this typology of social infrastructure back to life, arguing that the project adheres to a similar public program as historical precedents, albeit with contemporary additions such as a car park and convention center. As the convention center could service visitors coming from both the airport and the larger city, its scale is justifiable. However, the rest of complex is overscaled for its neighborhood.

The necessity of a 15,000-person mosque and parking for 1200 cars is questionable in a remote, low density residential area with poor pedestrian access. While historically külliyes acted as the heart of their neighborhoods, in close proximity to their users, this contemporary interpretation is surrounded by massive highways and steep elevations that hinder local residents’ use. Indeed, the government seems to have recognized the mosque’s isolation and plans to provide access through a (no doubt expensive) cable car. Yet, even if the complex was easily reachable, its location in a solely residential area lowers the number of potential daytime users, as residents must commute elsewhere in the city to work. All of these factors make clear that the government ignored the project’s context and instead prioritized promoting the societal role of Islam to people entering the capital. The historical social role of the külliye typology is here replaced with an image-based symbolic function. Located strategically on a hill where the road curves in a way that the complex is on-axis with Protocol Road, neither the project nor what it represents can be missed by drivers.

In addition to these examples that highlight the curated image of a state with strong ties to its pre-republican past, other projects implemented along the road merely aim to beautify the metropolis for high-profile visitors. The most significant of these is the clearance of gecekondu, or self-built squatter houses, along a stretch of Protocol Road. In her recent book, Mış Gibi Site, Tahire Erman recounts that prior to their demolition, whenever an important political leader was scheduled to pass through the area, the electricity was cut to conceal the houses from view. In 2005–06, 30,000 people were displaced as 6,500 houses were cleared, and since then the state-managed Housing Development Administration (TOKİ), has built 8,000 units, with an additional 13,000 slated for development.

Although most of the gecekondu lacked quality living conditions, the high-rise TOKİ blocks have their own shortcomings. Protocol Road was rerouted so that market-rate housing could occupy a larger, flatter site on one side of the road while new housing for former gecekondu residents were crammed on to a smaller, hilly site on the other side. Furthermore, TOKİ did not acknowledge or plan for the shift in lifestyle required of former gecekondu residents as they were moved from their low-rise garden homes to high-rise apartments. Not only is the project therefore a failure of social planning, it fell short of its original purpose to aesthetically improve the view from Protocol Road. While the low-rise squatter houses hugged the hill, preserving the topography’s natural silhouette, the monotonous high-rise TOKİ blocks erupt from gaping holes in the slopes held at bay with the massive retaining walls. One of the only ways to differentiate the towers is by their gaudy color schemes, made all the more garish at night by flood lights on the buildings and psychedelic colored landscape lighting, surely amounting to a distraction for drivers on Protocol Road.

Other “beautification” efforts along Protocol Road are only skin-deep. In order to create a uniform street façade, the government re-clad approximately 200 buildings overlooking the highway with red tiles. Yet, only the elevations facing Protocol Road—not every façade—were given this treatment. This Potemkin strategy neglects the fact that drivers can easily see the unclad sides as they pass by.

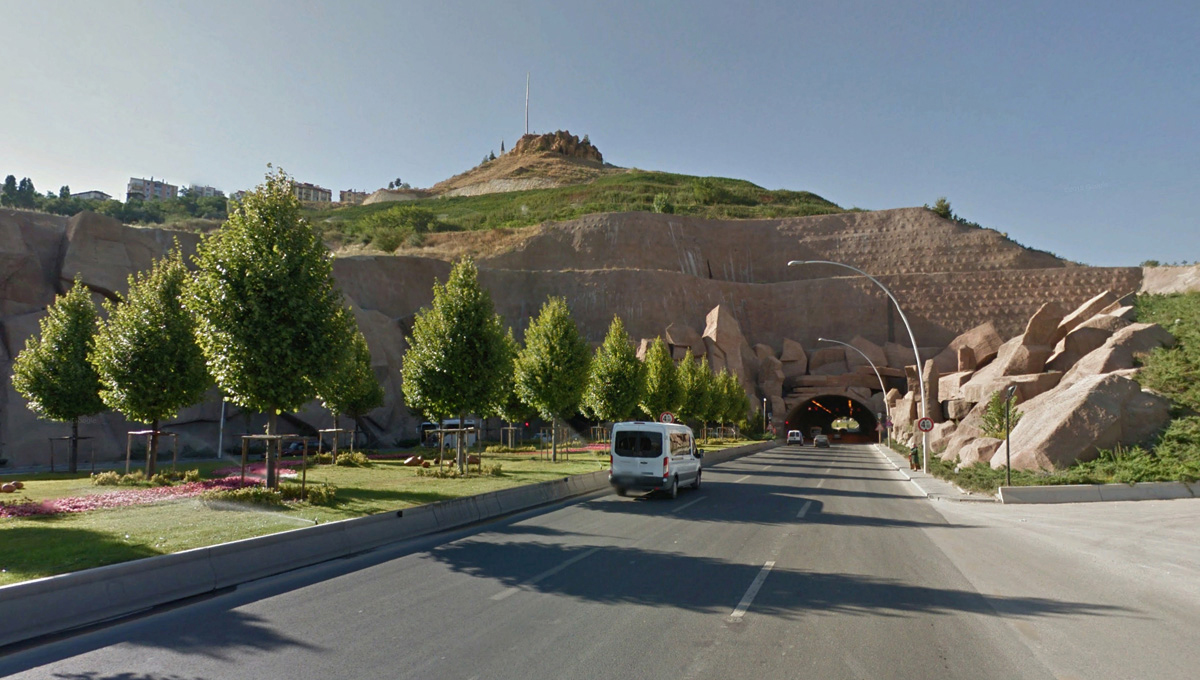

A similar approach was applied to the tunnels that mark the transition from the city limits to Protocol Road. The tunnel openings are surrounded by plastic rocks, but large concrete retaining walls remain visible above them. It is hard to account for the desire to hide a well-executed engineering project beneath an obviously fake appliqué beyond simple bad taste.

A comparable lack of taste guided decisions that were made by the government about the overall lighting design of Protocol Road. Aside from the floodlights on the TOKİ blocks and the equally vivid color scheme for the North Star Park below, blinding white lights inexplicably line the road between them. LED letters spell out “Welcome to Ankara” and “Goodbye,” in both Turkish and English, but, oddly, they are all located on the same side of the road, heading toward the city. Clearly, the government once again prioritized “beautification” over the well-being of drivers and residents.

Although there are other interventions along Protocol Road, the examples described above make it clear that the government produced these projects to direct the first impressions of high-profile visitors to Ankara and Turkey through landscape. While the government hopes to promote the image of a contemporary global metropolis, the application of old styles and inappropriate surface treatments undermines this effort and produces a haphazard sequence of urban events with little relation to one another. Furthermore, the lack of community participation or even input from outside consultants makes clear that the government has no interest in incorporating other viewpoints into the creation of this image.

Millions of Turkish liras have been spent “beautifying” a 40-minute ride for visitors, instead of actually improving the lives of residents. Thus, not only does this sequence of projects fail on its own terms to produce a coherent image of a successful metropolis, this image-making in landscape is a disservice to Ankara’s inhabitants.