It’s been ten years since The Wire’s final episode aired on HBO. To mark the occasion, there were several excellent reflections on the show’s impact on politics and popular culture, most notably, a comprehensive long read by Helena Sheehan and Sheamus Sweeney for Jacobin.

Sheehan and Sweeney’s article offers many insights into the state of contemporary urbanism. But given its scope, it quite understandably overlooks a scene which all critical urbanists should be compelled to watch, and one which attests to the glowing praise the series has received recently.

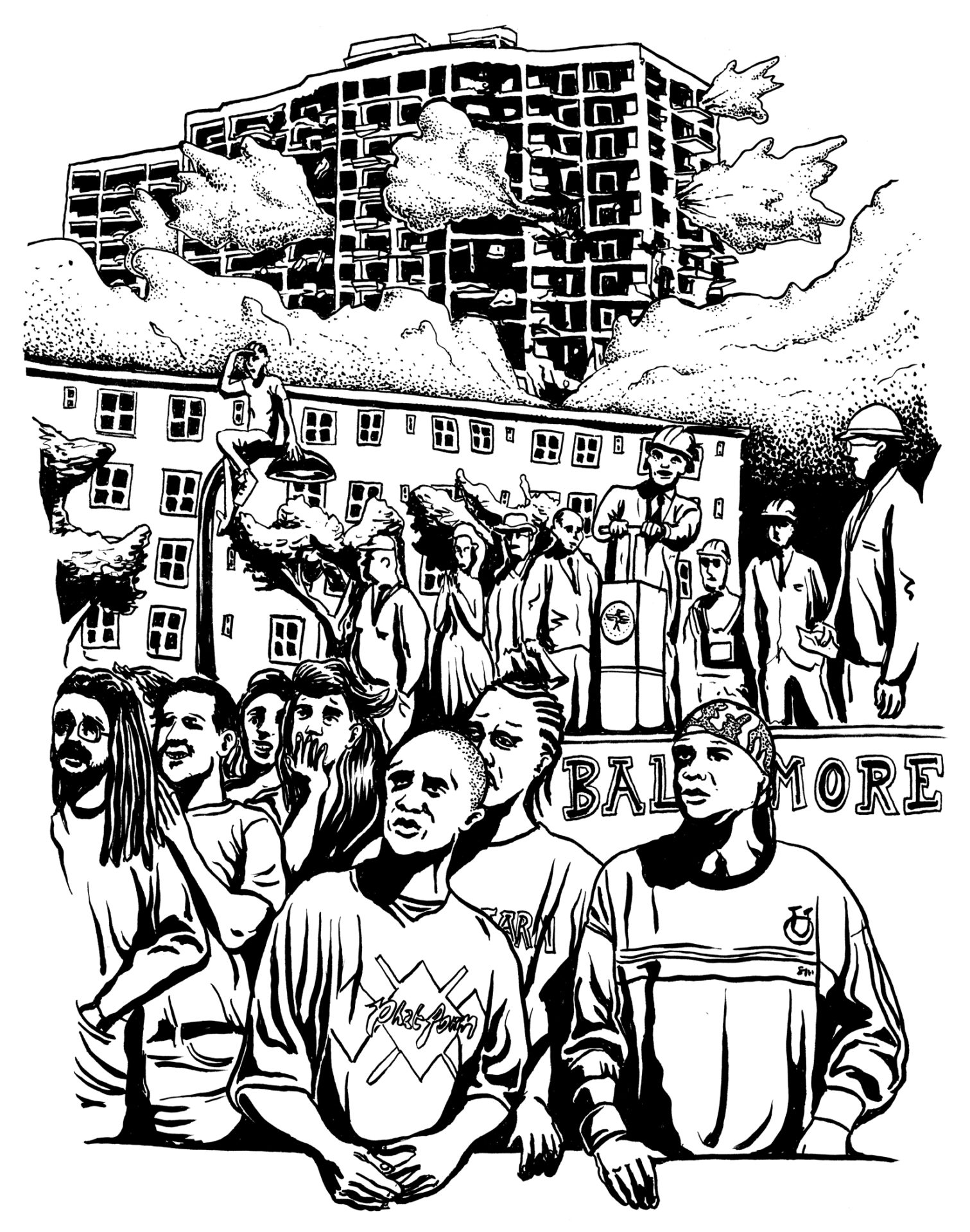

Falling at the very beginning of season three, the scene captures the demolition of a set of high-rise residential towers. The housing blocks, Franklin Terrace Towers as they are called, had provided the backdrop to several key scenes in the preceding series, constituting the central pillar of drug dealer Avon Barksdale’s West Baltimore empire.

While it only lasts a matter of minutes, you would struggle to find a more comprehensive snapshot of the main factors at play in the complex story of public housing. In it we see that the experience of living in what should essentially be a normal form of housing has been skewed by negative representations, institutional failure, and a real estate market which always acts against the interest of the urban poor.

The scene begins with two of the show’s main characters, Bodie and Poot, walking towards a crowd who have gathered to watch the impending demolition. On their approach, they debate the relative merits of getting rid of these high-rise blocks.

As low-level drug dealers who grew up in the neighbourhood, the two characters had spent much of their everyday life in the towers, both living and working. Yet they express markedly different feelings about the imminent demolition.

Poot cherishes the housing, recalling fond memories of time spent there: “I been seen some shit happen up in them towers, it still make me smile, yo.” In Poot’s view, no matter how bad their reputation, these towers shaped his life. They were home for him and for many hundreds of others. As such, they had a major impact on his sense of who he is and where he belongs. “I’m talkin’ about people.” he says, “Memories an’ shit.”

Meanwhile, Bodie is much less sentimental, essentially taking the view that towers are merely functional and economic, and that the experience of the people living them doesn’t matter at all. “Y’all talkin’ about steel and concrete, man.” He replies to Poot, “Steel and fucking concrete,” later explaining that, “they gonna tear this building down, they gonna build some new shit. But people? They don’t give a fuck about people.”

Taken together, both characters’ sentiments say something about the meaning of the Franklin Terrace Towers. On the one hand, housing is the container of a rich tapestry of human experience. On the other hand, they are also simply buildings, primarily meant to provide safe and reliable shelter.

As Bodie and Poot approach the crowd, their debate is punctuated by a speech from the city’s mayor, Clarence Royce. After some choice words about the legacy of the towers, and right before pushing down on the detonator, Royce concludes by asking the crowd: “Are you ready for a new Baltimore?”

This statement more or less encapsulates policymakers’ perpetual inability to understand architecture’s role in shaping the city. Royce suggests that a new Baltimore will arise simply by blowing up a building that had, as he states earlier in his speech, “come to represent some of the city’s most entrenched problems”.

There is a degree of doublethink evident in what the mayor says. While he acknowledges that the buildings are simply a representation of wider problems, he perpetuates the common misapprehension that the very design of the building is to blame for these problems.

This notion that the design of such tower blocks has a major role in the decline of certain neighbourhoods became wildly popular amongst housing policymakers from the early 1970s onwards. It drew heavily on the ideas of the architect Oscar Newman, and particularly his “defensible space theory”. The theory claimed that higher crime rates existed in high-rise apartment buildings than in lower housing projects. Mixing correlation and causality, Newman postulated that this was a result of residents having no sense of personal ownership or control over a building which housed so many people.

Few housing developments illustrate Newman’s faulty reasoning more than the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, whose famous demolition The Wire’s own demolition scene undoubtedly channels.

Situated in St. Louis Missouri, Pruitt-Igoe was a massive social housing development built in 1954 as a means of accommodating the increase in St. Louis’ population which the city’s housing authority (incorrectly) anticipated. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki, the architect who went on to build the first World Trade Centre, it was singled out by the magazine Architectural Forum as the “best high apartment” of the year when it was built.

However, policy failings in the build-up to the project’s completion meant that things went bad almost as soon as the first residents moved in. The most important of these failings was the lack of funds set aside for maintenance. While the Federal Housing Authority were willing to cover the cost of building the project, they were not prepared to provide the funding to maintain it thereafter. Instead, the high cost for maintenance of these complex structures had to come from rent revenues.

Yet since the anticipated population increase did not materialise, Pruitt-Igoe was critically under-occupied. This led to a downward spiral of under-maintenance, dilapidation, and the gradual departure of the project’s middle income, often white, inhabitants (a process referred to as white flight). By the early 1970s, less than 20 years after the buildings were completed, the housing authority decided that Pruitt-Igoe would be demolished.

A photo of the first demolition appeared on the front page of LIFE magazine in May 1972 as well as on the back of Oscar Newman’s book on defensible space, released in the same year. The picture came to represent the quintessential failure of the modernist high rise, which was increasingly coming to be blamed for the social problems prevailing in inner cities at the time.

As is clear, though, it was not the fact of their being tall or modernist, or any other element of their design which made the Pruitt-Igoe towers fail so catastrophically. Rather, the case of Pruitt Igoe offers a stark example of the great overlooked factor in the success or failure of high rise housing: maintenance.

Under-maintenance has always been a political decision. As shown by recent examples like the Heygate Estate in London, it has always provided a useful a means of justifying the removal of social housing residents in order to make way for wealthier private tenants. And right on time, The Wire’s demolition scene jumps in to capture this observation.

Bodie’s parting comment in his debate with Poot hints at who will be living in the area once the land is redeveloped: “these downtown, suit-wearin’ ass bitches just snatched up the best territory in the city from y’all.”

Just before this, he points out that the position of their territory, right in the inner city, gave them access to an extremely wide and lucrative market of customers. Yet, as such inner city locations have become more desirable to a wealthier demographic, the potential achievable rental income from the land has made the position of people like Bodie and Poot ever more precarious.

This disparity between the current rental value of a piece of land, derived, in this case, from Bodie, Poot and their neighbours in the high rises, and the maximum achievable rental value at its “best use” by those “downtown suit-wearin’ ass bitches” has been described as the “rent gap”.

The consequences of this disconnect were made abundantly clear in the recent fire at Grenfell Tower in London. In the years leading to the fire, the local council had allowed the tower to fall into a dangerous state of disrepair. Community activists and residents’ association organisers believe this was due to a deliberate campaign of social cleansing. The tower’s residents were not the sort of people the council wanted in the community. Just as with Bodie and Poot, they were poor, working class, and their home rested on highly desirable land which would be much more valuable to the local authority if they could find a way to sell it off.

By all accounts, Grenfell Tower was relatively structurally sound (one suspects the same goes for the Franklin Terrace Towers), but it was the addition of cladding that turned the tower into a tinderbox. According to planning documents obtained by The Independent, this cladding was added to improve the view for people living in luxury flats nearby, who had no doubt come to see social housing in a negative light.

Both the Grenfell tragedy and The Wire’s demolition scene are potent reminders of how dysfunctional housing policy is in our present capitalist system, and how dysfunctional it has always been. Rather than being seen as a place in which people live and make a home, share memories and leave traces, it is seen simply as a matter of “real estate”… just “steel and concrete”.

A longer version of this article appeared earlier this year in the German magazine Bauwelt.