In the 2016 short film Hyperreality, designer and filmmaker Keiichi Matsuda crafts a disorienting, even oppressive, portrayal of everyday life mediated by all-encompassing, immersive augmented reality. Set in the Colombian city of Medellín—and shot from a first-person perspective “filtered” through a speculative eyepiece interface—from the first frame, the protagonist’s senses are bombarded with a deluge of advertisements, games, music videos, animations, and cartoonish renderings of computer-generated architecture and nature.

Digital communications and social media platforms have become fully environmental in this vision of the future. Fragments of the overwhelming spatial logics and hyper-stimulating aesthetics of New York’s Times Square or Tokyo’s Shibuya Station are translated into a subjective and embodied experience; urbanism, in Matsuda’s future-world, becomes a form of media in itself. In one scene, the film’s protagonist-user (“Juliana”), becomes confused, even anxious, by a technical glitch which forces a reboot of her device while shopping for food, showing the viewer a brief glimpse of a un-augmented and totally featureless supermarket, clearly designed for the express purpose of accommodating a digital overlay. Matsuda’s film ultimately suggests that augmented reality may become so commonplace as to be essential to making sense of the world.

Hyperreality also extrapolates from, and radically accelerates, expectations for augmented reality’s future: expectations which have been largely conditioned by the technology’s first real-world success story, Pokémon Go. Darkly twisting Go’s nominally benign rescripting of urban space, the film portrays augmented reality as an inherently gamified, commercial, and homogenizing interface experience. Since the sharp rise and precipitous fall of Pokémon Go, a critical mass of popular and financial speculation has swirled around AR as a new form of mass entertainment. Despite the game’s failure to sustain its initial popularity, AR in general is projected to become a multi-billion dollar industry within the next ten years – utilized for leisure (and labor) and migrating across interfaces (from smartphone to wearables) to become an ever-present, normalized filter of human perception in built environments.

This speculative orientation, however, must be countered with a dose of history. Though the pace of technological change in the field has been swift, we should seek to challenge prevailing attitudes that see digital innovation as the exclusive province of entrepeneurial minds and venture capital. Shedding just a little historical light onto the relatively slow, collective, and complicated development of AR can help challenge the hegemony of “disruption,” and open up space for greater public debate into how, and for whom, this technology is being used.

Over the past couple of decades, artists and designers have developed augmented realities that propose vastly different, and often more radical perspectives of what a digitally-enhanced public realm could look like. Unlike Matsuda’s unsettling vision of AR as a layer of perception primed for economic exploitation, many AR projects instead provoke critical questions about the implementation of this novel technology and its potential to shift both the everyday experiences and political economies of architecture and cities. What does it mean to filter public space through a highly personalized form of digital sensing? How does the collapse of virtual onto physical space reorder established ways of understanding landscapes? What are the potential pitfalls and possibilities of a technology that promises re-enchantment of space, yet relies on privately-owned data infrastructures and a military-operated ensemble of near orbit satellites?

Growing interest in location-based AR projects, beginning in the late 1990s, can be in part attributed to the confluence of art and networking technologies which emerged out of the gradual popularization of the Internet and the influence of “net art.” Net art, according to critic Josephine Bosma, has often concerned itself with “the public domain as a virtual, mediated space consisting of both material and immaterial matter,” indicating a conceptual and ethical foundation for augmented reality’s radical leap from the space of the screen to a “hybrid space” mixing real and virtual elements.

Near the tail end of the 20th century, pseudonymous author and technologist Ben Russell released The Headmap Manifesto — a utopian vision of augmented reality referencing Australian aboriginal songlines and occult tomes, while pulling heavily from cybernetic theory and the Temporary Autonomous Zones of Hakim Bey. At turns both wildly hypothetical and eerily prescient, Headmap explores in-depth the implications of “location-aware” augmented reality as a kind of “parasitic architecture” affording ordinary people the chance to annotate and re-interpret their environment.

Around the same time, artist and scholar Teri Rueb began developing her pioneering, site-specific augmented “soundwalks,” some of the earliest and most influential examples of GPS-based art practice. Iinfluenced by land art practitioners such as Robert Smithson and Richard Serra, Rueb’s work identified the critical potential of locative AR as a direct mediator of spatial experience, capable of revealing hidden layers of meaning within landscapes. Beyond land art, a number of early AR practitioners and theorists explicitly identified the Situationist International (and even Archigram) as conceptual touchstones for the kind of digital enhancement, and potential subversion, of space made possible through augmenting reality.

Compared to the pastoral setting of Rueb’s work, other projects —such as the early interactive AR game Can You See Me Now? from the UK-based multimedia arts group Blast Theory or The Yellow Arrow Project, which ran from 2004 to 2006 — took a decidedly urban turn. Yellow Arrow, for instance, utilized uniquely-coded stickers and SMS text messaging to “draw attention to different locations and objects—whether a back-alley mural, a favorite dive bar, or a new perspective on a classic landmark.” This project’s mixing of digital and physical media, as well as its creator’s explicit references to street art and psychogeography, seemed to hint at a more subversive agenda. However, Yellow Arrow, produced by Counts Media — an “arts-driven entertainment company” — ultimately embraced more entrepreneurial uses for its platform, including a collaboration with travel guide publisher Lonely Planet on a book called Experimental Travel. One of its founding members, Jesse Shapins, would eventually become the Director of Public Realm & Culture at Alphabet’s urban start-up Sidewalk Labs (now largely known for its “smart city” machinations along Toronto’s waterfront).

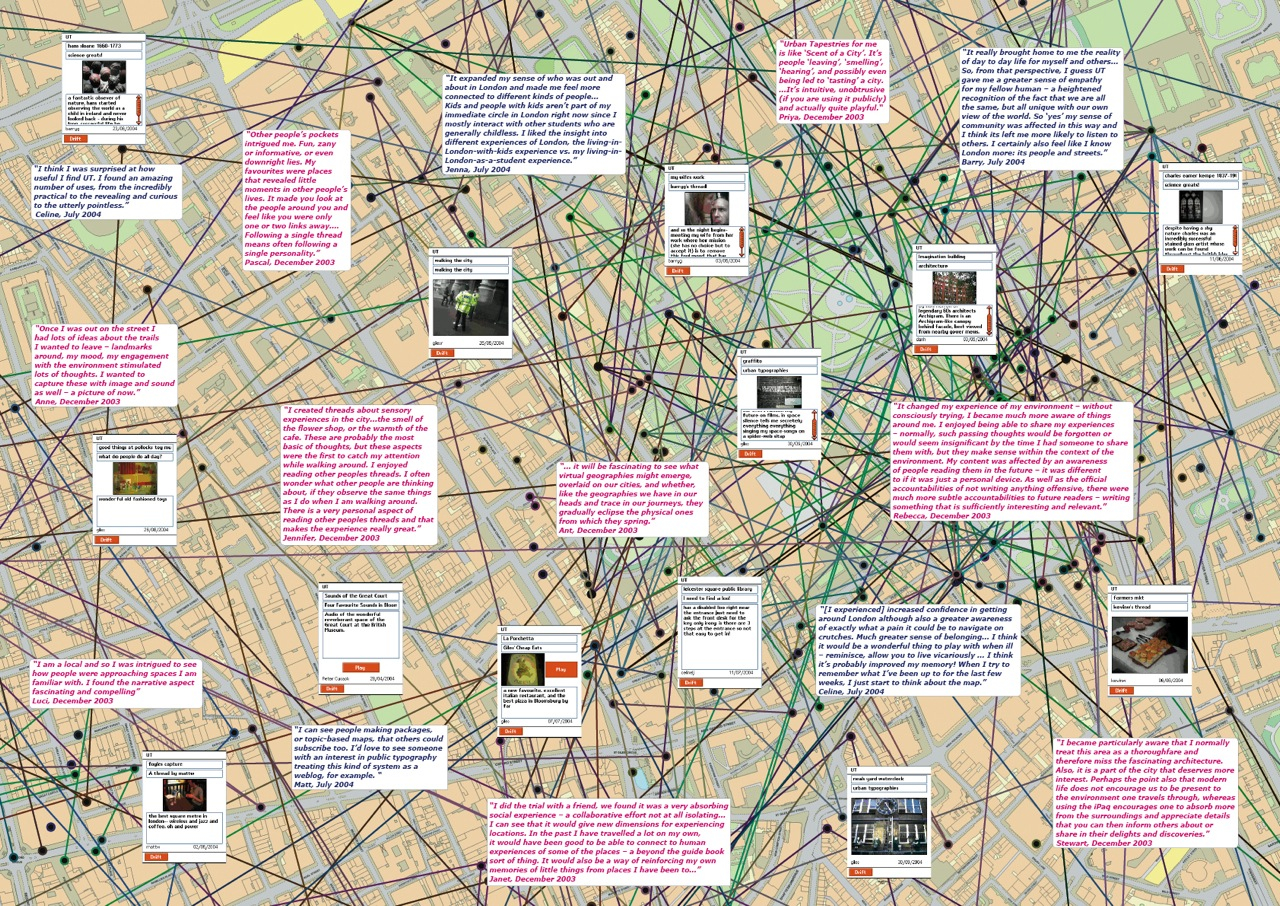

In the UK, an annotative “montage” project called Urban Tapestries launched in 2004 as “a research project and experimental software platform for knowledge mapping and sharing” oriented towards establishing a “public knowledge commons.” This platform, similar in concept (if not execution) to the not-yet world conquering notion of social media, encouraged a range of geographically-bound participants in central London to share personal stories and artifacts from everyday life through a wireless, networked application built for bygone personal digital assistant, or PDA, devices. The project lasted three years, resulting, beyond the platform itself, in a number of essays, reports, videos, workshops and installations; all requiring the technical and financial support of a partners such as the London School of Economics, Birkbeck College, Orange Telecom, Hewlett-Packard Labs, France Telecom R&D UK, Ordnance Survey — a robust mix of educational and governmental institutions, along with private technology firms. The project’s goal of establishing an augmented and geolocative “public knowledge commons” was, from the beginning, complicated by such partnerships and their implications, predicting in part the ambivalent status of privately-owned “public” social media networks today. Yet by employing anthropologists and drawing from the Mass Observation movement of the 1930s, Urban Tapestries introduced a more thoughtful and collectively-generated vision of spatial augmentation, and of mobile digital technology as a whole.

Following the release of the first iPhone and advancements in mobile phone cameras and processing power, AR began to move toward the more visually-dominant experiences we are familiar with today — in the process also opening up possibilities for more explicitly political projects. The group 4 Gentlemen, for instance, embraced AR as a tool for criticizing oppressive government policies in China. A collective of exiled Chinese artists and one American artist, 4 Gentlemen (taking their name from a group of intellectual dissidents central to the Tiananmen Student Protest in 1989) developed a series of works that digitally recreated in situ both the famous “Tank Man” image and the “Goddess of Democracy” statue — two symbols of the Tiananmen protest which have defined the struggle for democracy and human rights in China since. The group would eventually join a number of other digital artists in 2011 for AR Occupy Wall Street, an augmented tribute to the famed protests movement organized by the anti-capitalist Manifest.AR collective.

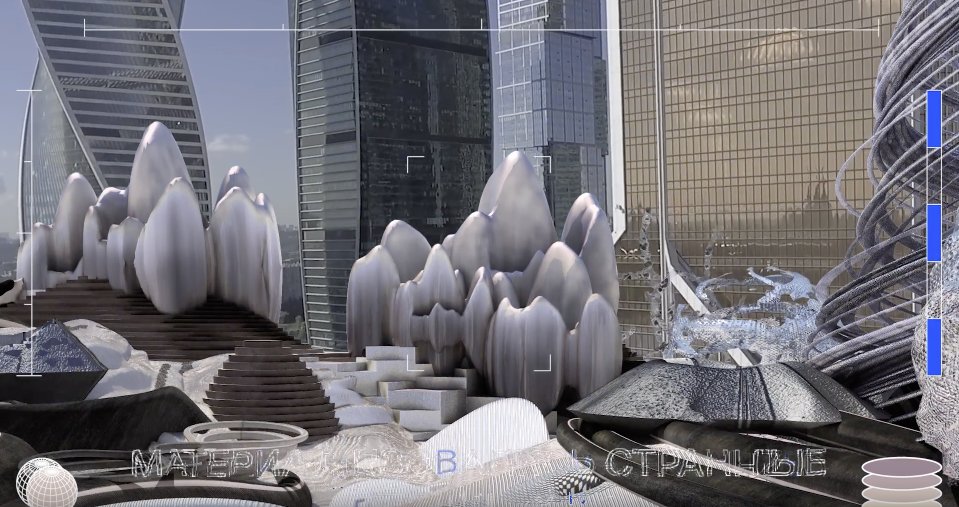

New media artists have created contemporary AR works that creatively challenge dominant political narratives. John Craig Freeman’s Water wARs overlaid a fictional pavilion for “artists/squatters and water war refugees” in Venice’s Piazza San Marco, while his Frontera de los Muertos project resulted in thousands of 3D-rendered skeleton effigies (based on a traditional form of Oaxacan wood-carvin) geo-tagged to the precise coordinates of where the remains of migrants illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border have been recovered. Tamiko Thiel’s body of work, going back to the 1980s and intersecting virtual reality as well as performance art, includes site-specific AR “installations” such as Garden of the Anthropocene, which explored the effects of climate change on the future of plant life. Even AR gaming has been touched by this more critical turn. Born out of The New Normal program at Moscow’s Strelka Institute, Patternist mixes a mysterious science-fiction narrative with critical explorations of real-world urban typologies and their spatial and social affordances.

As the augmented landscape becomes ever-more crowded with commercial titles like Pokémon Go — similar games linking to the Harry Potter and Jurassic Park franchises are reportedly in the works — it is refreshing to see a newer crop of AR projects that continue the technology’s surprisingly rich history of experimentation. And as this landscape increasingly constitutes a public realm in and of itself, a collection of hybrid real-virtual public spaces, there are even glimmers of direct challenges to its creeping privatization.

In late 2017, Snapchat collaborated with Jeff Koons to develop a geo-tagged AR public sculpture in New York City’s Central Park. Within just a single day, the work was “vandalised.” Rather than hacking Snapchat, the culprit, artist Sebastian Errazuriz, built an alternative, graffiti-bombed version of the Koons sculpture assigned to the exact same coordinates as the original piece. Though the act may have ultimately been more symbolic than effective in its challenge to Snapchat’s augmented public space intervention, Errazuriz’s stated motivations capture some of heated tenor of debates to come:

What does the virtual space that “belongs to us” look like? Would could it look like? We might imagine a future as steeped in AR as Matsuda’s Hyperreality, but where instead of a hybrid landscape dominated by ads and obfuscating distractions, augmented overlays are used to highlight the hidden dimensions of place, or serve as a distinctly spatial platform for alternative forms of communication and culture. Inverting the vision of a commodified hybrid landscape, the seemingly inevitable barrage of immersive, interfacial capitalism could perhaps be transmuted into something democratic, artful, and even beautiful: a conduit to mobile urban discourse and learning; to collectively owned and managed hybrid spaces, and to community as a social body intersecting physical and digital worlds. But if this more hopeful image of an AR-saturated future is to come to fruition, it will require a deeply collaborative spirit between programmers and urbanists, artists and technologists, activists and educators — and most certainly architects as well.