Last Friday, 28 September, students occupied the P.C. Hoofthuis, one of several buildings in Amsterdam’s city centre belonging to the University of Amsterdam (UvA). It was evicted the same day by plenty of police in riot gear. Some displaced teachers moved their classes outside, with one philosophy class even moving into an adjacent café. Most classes, however, were either cancelled or moved to the nearby Roeterseiland campus, where recently realised building complexes provided ample room for extra classes to take place thanks to the university’s recent effort to adopt a campus model.

All this happened during a month in which the university — the Netherland’s largest — welcomed close to 10,000 new students, over 800 more than last year. Housing teaching amenities for an ever-increasing amount of students has been an issue ever since the late 1960s, as have discussions about what form these should take. The activist and progressive milieu of the 1970s resulted in the UvA adopting an approach that stayed true to its long tradition of being interwoven with the city of Amsterdam and its urban culture. However, the current developments that concentrate its presence in four campuses fail to prolong a history of social involvement and responsibility embodied by 1980s-era buildings such as the P.C. Hoofthuis. By vacating and selling off its properties scattered through the city centre, the University of Amsterdam is becoming complicit in the move towards a privatised and segregated cityscape and culture.

With a history dating back to the early 17th century, the University of Amsterdam has always had a prominent place in the city’s urban, social and political history. Up until the mid-20th century, the mayor of Amsterdam also served as de-facto director of the university, and for a long time it was the city’s government who appointed professors. Largely funded by the local rather than the national authorities, the University of Amsterdam was for a long time known as the Gemeente Universiteit [‘Municipal University’], until it was ‘nationalised’ in 1961. After that, subsequent acquisition of numerous properties throughout the city centre (the outcome of a rapid and unexpected rise in the number of students rather than a deliberate or carefully thought-through policy), assured that the UvA remained closely interwoven with the city of Amsterdam: the many locations throughout the historic city centre — including a number of canal houses — meant that student and urban life became thoroughly entangled.

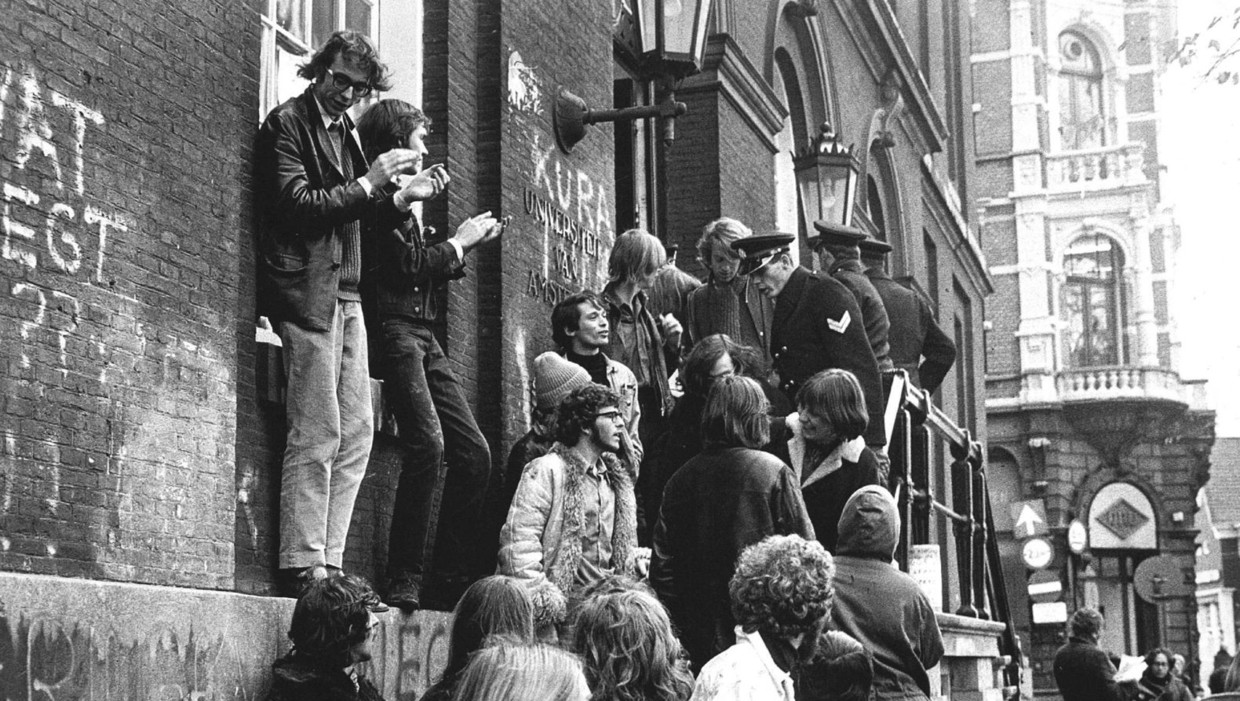

Significantly, the university’s ‘seat of government’ is located at the imposing Maagdenhuis building at Amsterdam’s Spui square, an important civic space that also served as a protest site for the city’s thriving counterculture from 1965 onwards. Inspired by the events of May ‘68, students of the University of Amsterdam occupied the Maagdenhuis in 1969, demanding a more democratic organisation of the university. This episode would set a precedent for many more instances of protest and occupation, with the Maagdenhuis having been occupied no less than twelve times in the past fifty years. The most recent of these, in 2015, was preceded by a public protest on Spui square during which the threshold between public and private was physically undermined: the building’s door was broken open and the main hall claimed as public space.

The use of occupation as a form of protest is of course not limited to the academic context, especially in Amsterdam, which has a long tradition of squatting communities fighting for more social, inclusive and less marketised housing. This became evident in the early 1970s, when Amsterdam was attempting to modernise the city through reconstruction schemes that allowed for radical infrastructural and urban interventions, until it reached a critical point of resistance at the Nieuwmarkt area. Following significant protests, sometimes accompanied by outright riots, a coalition of residents and squatters petitioned the city government to abort their plans. After winning a competition set up to generate alternative designs, the architect partnership of Theo Bosch and Aldo van Eyck was invited to submit a new plan. The latter had acquired an international reputation through his involvement with the avant-garde Team Ten group, which had been championing a more contextually sensitive strand of modernism. Actively involving both the city council and the local population, they came up with a scheme that replaced the planned office developments and four-lane expressway with a variety of social housing complexes. In 1972, it was decided to cancel the expressway, allowing for the original street structure on top of the metro trajectory to remain intact.

Van Eyck and Bosch empowered the local community to take control of ‘their’ city, much like the protests at the Maagdenhuis fostered the students’ involvement with ‘their’ university. And just as the Nieuwmarkt area protests had prevented large-scale developments in favour of contextually sensitive urban interventions, the 1970s-era democratisation of the University of Amsterdam had resulted in a move away from the scheduled large-scale ‘tabula rasa’ extension plans in favour of more modest growth plans that focused on the city centre. The university administration’s long-cherished dream of large new campus areas — in some scenarios planned to be realised as far away as the newly claimed land of the Flevopolder — were put on hold and finally abandoned.

This new course by the University of Amsterdam resulted in the office of Bosch & Van Eyck receiving another major commission in inner-city Amsterdam just a couple of years later. A new building for the university’s humanities faculty was to be built on a prime location just a stone’s throw away from another of the UvA’s inner-city landmarks, the Bungehuis, which was acquired by the University around the same time. It is significant that the University of Amsterdam, which from the Maagdenhuis occupation in 1969 onwards had become known as one of the most progressive universities of the country, picked Bosch and Van Eyck as its architects of choice for the new inner-city university building. By selecting the architects responsible for the Nieuwmarkt area for its own construction project, the UvA demonstrated an awareness of its urban as well as its social responsibility.

In designing the so-called P.C. Hoofthuis, Theo Bosch (claiming full authorship) applied his maxim that ‘every building should give something back to the city’ instead of merely subtracting space from it. Part of this aim was thought to be realised by being ‘open’ to the street through various alleys, porticos and incorporated stores. But the building also meets this aim in another important yet rather more intangible way: by facilitating urban dwellers reciprocal exposure to different walks of life. The Spuistraat was home not just to students but also to squatters, sex workers, shopkeepers and bartenders — all of whom share the same sidewalk, which arguably enhances social cohesion. Unfortunately, the design of the building did not realise these principles quite the way its designers intended them to. A planned public crossing through the building was never realised, and many of its semi-public areas have over the years been curbed by fences or other exclusionary spatial tools. Despite all this, however, the project still resulted in an extraordinary building with a uniquely open lay-out, abundantly lit rooms, and idiosyncratically articulated spaces.

Unfortunately, the contemporary strategies of the project developments commissioned by the University of Amsterdam are a far cry from what they achieved with the humanities faculty building at the Spuistraat. With dreams of campus models making their way back into the minds of the university’s neoliberal directors, many of the UvA’s characteristic buildings are being sold off to the highest bidder, in order to consolidate the university’s real estate assets into four campuses. The science and medical faculties are now housed respectively at the eastern and south-eastern edges of the city, whilst the humanities and social sciences will remain in the city centre. The latter are located in what is known as the Roeterseiland Campus, a large complex containing streets, bridges and even a canal with faux brickwork. Resembling a combination of the characteristic red brick of Amsterdam’s streets with the anonymity of mirror-glazed office towers, this campus (whose current form consists of an almost completely redeveloped version of existing UvA property in this area) received this year’s RIBA International Award. However, by realising an essentially anti-urban typology in a typically urban environment, it detracts from the characteristics of the campus’s surrounding neighbourhood. Perhaps one of the most consequential aspects of this approach is the fact that the whole area consists completely of privately-owned public space (so-called ‘POPS’). Though other city dwellers are not actively barred, only students have any business coming here, a fact that is emphasised by the mandated signage marking the borders of public and private space that accompany every entry point of the campus.

Apart from an increasing segregation of student and non-student city dwellers — questionable at best, especially given increasing calls for universities to be less ‘inward-looking’ and more engaged with society — it also undermines the UvA’s long tradition of protests. Whereas public space has to abide by municipal rules (after all, a protest is allowed or denied by municipal authorities; in fact, Amsterdam’s late mayor Van der Laan acted as a mediator between university board and protesters during the 2015 protests), private space can be legislated according to the whims of its owner. This has resulted in the university calling the police on peacefully protesting students because they were ‘trespassing’ on their premises, creating quite worrisome scenes of law enforcement violently ejecting students from the quasi-public spaces of the Roeterseiland. This difference in jurisdiction was reemphasised during the most recent occupation of the P.C. Hoofthuis, where mayor of Amsterdam Femke Halsema (unsuccessfully) tried to enter the building to negotiate with the students before it was cleared by police.

With three of four campuses complete, the final humanities-oriented campus is scheduled to be realised on and around an inner-city complex consisting of historical buildings tied together through a number of additions dating from the 1980s, including a pavilion designed by Theo Bosch. Laid out around a street that serves tourists as much as students, the area also contains several housing units, resulting in a public atmosphere. Dubbed ‘University Quarter’, the name of the inner-city campus pays clear lip service to the recent trend of neighbourhood branding. Over the last five years, at least fifteen Amsterdam neighbourhoods have been renamed as a ‘quarter’ – the Hallenkwartier being the most infamous one. The last few steps of the development,including the board of directors vacating the Maagdenhuis for a more anonymous location, could very well be the final nail in the coffin containing the urban and social responsibility that the University of Amsterdam took upon itself so well in the past.

The policy of focusing on campuses instead of buildings scattered throughout the city results in several negative repercussions. Firstly, the sale of properties outside the campus makes the university complicit in the hotel fever currently spreading through the city. The aforementioned Bungehuis, which was also occupied during the 2015 protests and proved to be a formidable fortress that required significant efforts to be cleared by police, was sold and has been revamped into has a Soho House, entrance to which requires a membership costing 1500 euros per year. The P.C. Hoofthuis potentially awaits a similar fate. Here, an additional risk exists: since it does not enjoy the listed status of its Bungehuis twin, private developers could wreak havoc on this monument of post-war urban renewal. Recent alterations to significant architecture of this period has shown that Amsterdam’s monuments and heritage department is not up to speed with protecting this kind of architecture, making the whole matter even more pressing.

Secondly, questions remain about how the proposed new inner-city campus will function in an urban and social sense. A new university library, currently located across a canal near Spui square, is planned to be housed on the new campus as well. Renders of the proposed design sport a newly created atrium full of happy healthy students, and although the accompanying texts mention that other ‘visitors’ of the complex are welcome to wander the campus too, it remains to be seen if the current public character of the area remains intact. The outlook is even grimmer with regard to places for dissent, protest and occupation, which are greatly diminished since the area around Spui and Spuistraat will no longer house significant university locations. The extent to which the new campus will be a public place that allows for protest seems limited at best, especially given the already mentioned experiences at the Roeterseiland campus. In any case, since protests are as much about literal manifestation as they are about generating discomfort to those against whom the protest in directed, the opportunity to publicly manifest dissent at UvA buildings is greatly reduced by the curbing of the university sites’ public face (and legal status).

This is not just bad for those wanting to show protest and dissent, but also bad for the way in which university and city are connected to each other. By consolidating all of its locations into campuses, the public presence of the university will be greatly reduced. The ‘physical filter bubble’ of a campus lacks the value inherent value of a building more explicitly connected to the city, like the Maagdenhuis, P.C. Hoofthuis and Bungehuis were. In an age of devastating privatisation and neoliberalisation of educational institutions, ever-increasing cuts to university budgets, scepticism of academic knowledge and practice, and academics facing general reproaches of elitism and ‘ivory tower attitudes’, the explicitly public and engaged character of the university might help in overcoming some of these hurdles.

By having a public presence in the city, especially through socially engaged architecture and urbanism, universities have the ability to play an important role in the future of urban life, as the UvA has been doing for Amsterdam for the past three centuries in general and the last five decades in particular. What a shame it is that the University of Amsterdam is wasting this opportunity as well as its legacy by blindly following real estate logics, risk aversion, and campus ideology.

Header image by Hans Foto.