On October 8, 2018, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a dire new report warning of the ever-shrinking window of time in which humanity can avert the worst effects of a warming world (if it can at all). Though the full-throttle march into the Anthropocene might not be such shocking news to everyone, the report has thrust climate change in general back into the mainstream spotlight: particularly, among other crises, the threat that superstorms and sea level rise pose to cities.

There has been no lack of architectural responses to the threat of rising tides, especially in the metropolitan cities of the Global North; in fact, what might be called ‘climate megastructures’ have become something of an entire genre of architectural proposal, both real and fictional.

Going beyond more prosaic calls for the sustainability of individual buildings, climate megastructures operate at the scale of neighborhoods, cities or regions. Some are imminently buildable, based on contemporary technologies and knowledges up to the task of mitigating sea level rise and the increasing frequency of storms associated with it. Others are far more speculative and cleave to a faith similar to that found in climate geoengineering — the belief that humanity can, someday, figure out a technological magic bullet that can stop or even reverse the worst of climate change.

Large, infrastructural-scale thinking is a first step in the right direction towards coping with a problem as daunting and inevitable as sea level rise. But too often, both of these categories of climate megastructure share a common, deeply flawed assumption: that architecture can, and should, be deployed to rescue the urban status quo in the face of existential threat. “Green” megastructures that dutifully fulfill their role as an economic investment first — or just ignore their own place in a global real estate industry that ensures the consequences of climate change will be unevenly felt — might be “thinking big,” but fail to think systemically. When architecture proposes to save the flooding cities of the world, who or what exactly is it trying to save?

In New York City, a pillar of the global economy, the answer couldn’t be clearer. The Big U, a project led by Bjarke Ingels Group in response to the The Rebuild by Design Hurricane Sandy Design Competition, proposes to ensconce Lower Manhattan in a continuous, 10-mile-long amenitized flood protection zone, creating new parks and public spaces that would function as a barrier during storm surges. Initiated in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, the project is branded, in part, as an attempt to protect nearly 100,000 vulnerable low-income residents on the city’s Lower East Side. But the Big U team is not shy about selling its barrier primarily as an investment for protecting a local economy generating more than $500 billion annually — especially through tourism, to which the megastructure itself hopes to contribute significantly.

Notwithstanding the scaling back of promises made to the (increasingly displaced) low-income communities referenced in the plan, the Big U’s lip service to “social infrastructure” rings somewhat hollow when considering that it is sited adjacent to some of the wealthiest areas of one of the wealthiest cities in the world, as well as that city’s most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. Not surprisingly, the plan wishes to have its cake and eat it too: to mitigate storm damage, while also spurring economic growth with the addition of highly-coveted public space, funded, in part, with private dollars. Even less shocking is the fact that The Big U is, by a wide margin, Rebuild By Design’s best-funded project, and the centerpiece of an ensemble of mitigation plans for NYC that privileges economic points of interest and more affluent risk zones.

While The Big U continues to navigate the complex logistical and political nuances of building in an actual city, other proposals, less bound by realism, flourish in New York’s architectural scene. In response to a 2017 commission by New York Magazine to imagine the future of the city’s built environment, Mark Foster Gage Architects developed a dramatic proposal to dam the East River, effectively draining it to a new “valley” with over 15,000 acres of new gardens, farms and parks. The bravado of such a proposal and its fantastical renderings certainly spark the imagination. But along the edges of verdant rendered pasture — punctuated by structures echoing the designer’s typical sci-fi, kit-bashed aesthetic — one finds a city that looks exactly like the one which exists today. Though the proposal’s “epic-scale thinking” accounts for increased food production (“Catastrophe prevention is always better when it includes fresh produce”) and provides an “unparalleled opportunity for the city to engage in the construction of massive, next-generation, geothermal wells,” the political economy of such a huge transformation is not even so much as an afterthought.

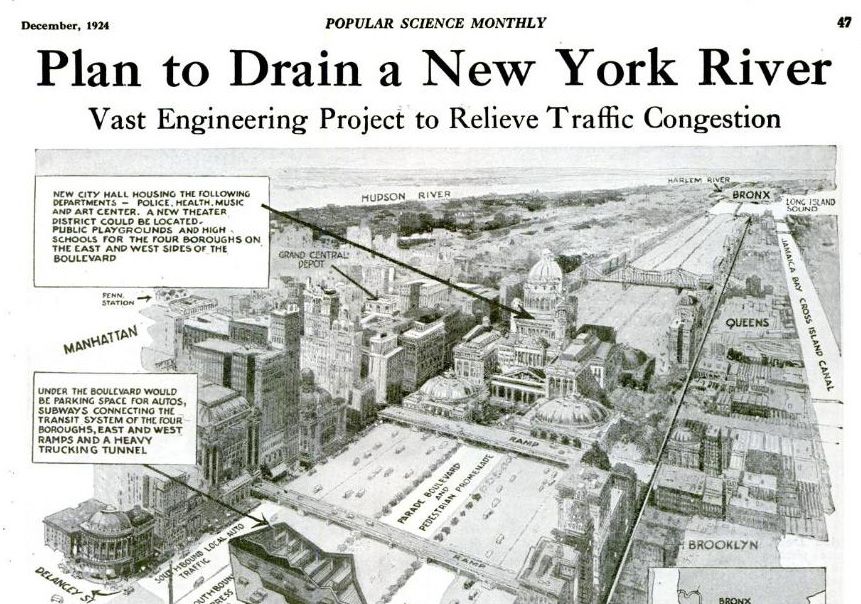

Ironically, ambitious plans to drain New York’s rivers have gained traction in the past, though with different goals, such as alleviating traffic, increasing density, or connecting Manhattan to New Jersey. And though these schemes may seem just as preposterous as an East River Valley, they actually speak more truthfully to the realities of capitalist real estate development and American notions of infrastructure planning. The creation of new terra firma, even for the purposes of mitigating climate change, is the creation of more exploitable land. The architectural speculation of Mark Foster Gage would necessitate (assumes?) an unprecedented social, public investment of the kind that just simply does not happen in a modern, neoliberal economy.

In all fairness, there is something innately appealing about the design affordances of a Big U, or the sheer ingenuity of a East River Valley. And it would be a mistake to retreat into total cynicism or nihilism — we simply cannot afford that. But looking beyond the conflicts posed by increasingly public-private (or just private) means of addressing it, there is a widespread inability within architecture as a discipline to meet the coming climate crisis on its own deeply ecological terms. Spatial solutionism takes on a vaguely ridiculous tone in the face of change that threatens existing patterns of human habitation (see: seawalls) or even human existence itself. The impulse towards optimism is not without virtue, but the familiar refrain that speaks of climate change as an “opportunity” undercuts the true gravity of the situation, especially for the people who will suffer most, or have already suffered, because of it — disproportionately people of color living in the Global South.

The never-realized “Great Garuda” seawall in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Architecture, in practice, too often feels culpable in the delusion that the neoliberal city can be made more resilient — so that its exploitative qualities may endure in the face of its own horrific blowback. Despite their audacity, existing climate megastructures often betray a conservative development logic: that even planetary ecology must conform to norms of economic growth, private property, and land use. Yet architecture, in its more theoretical dimensions, also does not seem up to the task of grappling with the severity of climate change. Having been long depoliticized, and more closely allied to philosophy (from which it frequently gleans only purely formal ideas) than disciplines like sociology or anthropology, architects too often lack a real praxis: a connection to the real struggles of people seeking to exert more power over their own lives and places, and by extension, over the response to existing and future climate crises.

Confronting climate change will require engagement with efforts to dismantle material and ideological systems driving mass extinctions, food and water scarcity, political oppression, inequality, violence and war — products of our current social order which are already, or will be, exacerbated by rising temperatures and sea levels. Climate megastructures might have some role to play in such struggles. But it is only through an activist lens that we might be able to answer that question — what exactly are we trying to save? — that can link “epic scales” to the lived realities of a precarious future.