The ongoing pandemic, coupled with economic chaos and a conflagration of demonstrations, has produced a condition in which everything seems to be going impossibly fast while standing perfectly still. Yes, the pandemic is still on, a fact that seems to be rapidly becoming a cudgel, even as police forces across the United States attempt to break the back of protests in cities across the country. Any hope of a concerted governmental response to coronavirus in the United States has exploded, even as the number of confirmed cases surges well past the two million mark. For some, however, there are glimmers of promise in a technological fix succeeding where medical and public health approaches have thus far failed. These fixes fall into three general categories — digital contact tracing, symptom tracking apps and immunity certification. Of these three, digital contact tracing has been the most widely touted as a silver-bullet palliative impeded only by the success of getting people in so-called “free countries” to live with it.

Detractors of digital contact tracing slot it neatly into a familiar narrative which treats surveillance technology as a titanic force, locked in eternal battle with individual “liberty”. The ceaseless focus on the personal as the unit of surveillance cleverly shifts the rhetorical focus away from collective considerations. Spaces, and the masses which pass through them, are the subject of surveillance, and both are animated and given form by remaking the city, through the addition of sensorial capacities, into a data extraction machine. Surveillance is not interested in uncovering personal secrets, but in the ability to track movements in space en masse — like soldiers and enemy combatants in a theater of war — and then to turn that collective activity into decipherable patterns.

Contact tracing (the non-digital version) has been the undisputed de-facto response to infectious disease outbreaks for years. It is the manual process of tracking and reducing possible cases of a disease by pairing tracers with infected individuals to build timelines of transmission and preemptively isolate those that may have come into contact with the infected. Contact tracing is a process, not a cure — and an extremely laborious one at that — but it has been proven effective in disparate locations and dealing with a variety of diseases. Contact tracing lives and dies by the number of tracers that can be brought to the field. Public health policy experts have recommended that the US have 300,000 contact tracers working full time, yet as of April 28th, it was estimated that under 8,000 tracers are currently working in the US.

That’s where digital contact tracing comes in: it offers the illusion of a competent response to the pandemic, while simultaneously solving this labor problem by automating the entire discipline. Where originally building a model of transmission was the object, digital contact tracing instead obsesses over predicting the already infected to an acceptable degree of accuracy. If analog contact tracing is focused on the activity of community relationships, the digital version views space as a pure, empty topological field where networks are ignored in favor of adjacency, and individuals are reduced to geotagged points of data. Once rendered down in this way, data can then be sieved through algorithms to guess one’s infection status, with the hope of arresting transmission at its source. Automation only succeeds by mutating the original task of contact tracing beyond recognition.

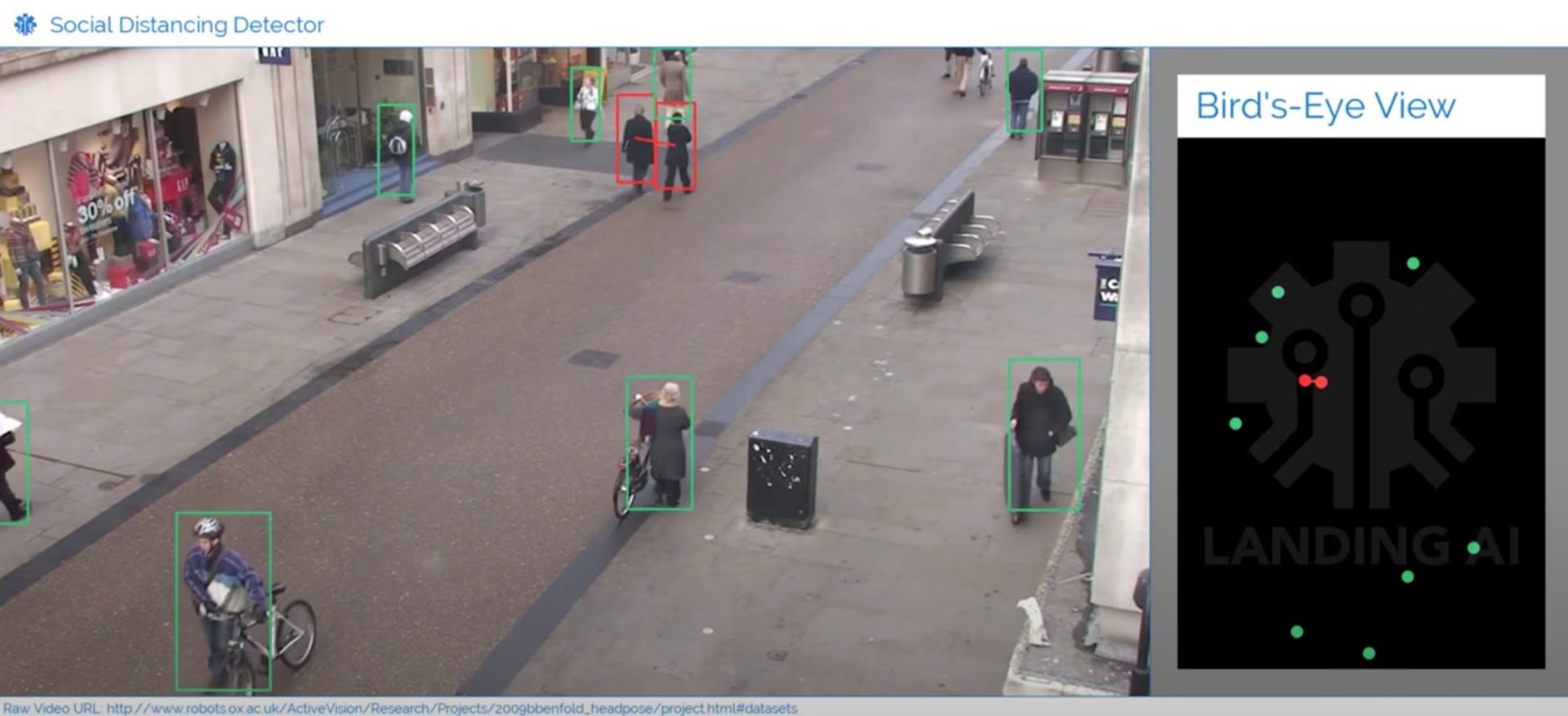

There are several proposals in play right now. Google and Apple are working on a “decentralized” system using Bluetooth signals from a user’s phone, with plans to eventually embed this functionality into their respective operating systems, used by three billion people globally. At the same time, the US Department of Health and Human Services has contracted with data analytics behemoth Palantir Technologies for a “centralized” contact tracing system using the company’s Gotham and Foundry data suites, organized under the umbrella of a program called “HHS Protect Now”. The Protect Now platform is designed to collate 187 datasets such as hospital capacities, geographic outbreak data, supply chain stress, and demographic info datasets into geospatial predictive models with the express goal of determining “when and where to re-open the economy”. Other notable, but tertiary, approaches include landing.ai’s AI tool to monitor social distancing in the workplace or the infrared camera system in place at Amazon warehouses, Whole Foods stores, and some factories owned by Tyson Chicken and Intel, both of which represent technologies which may easily be deployed at scale in public spaces.

Still from a video demo of landing.ai’s “Social Distancing Detector” software, deployed on a public street.

Google, Apple, Palantir, and the constellation of smaller tech companies poised to rake in enormous profits off pandemic platforms are not just in the right place at the right time to “offer their services”. Healthcare is an intensely lucrative line of work, and the tantalizing mirage of skyrocketing profit draws startups and giants alike, unconcerned with an admitted lack of healthcare knowledge. Both Google and Apple have been scratching at the door of healthcare for years, hoping to carve out a piece of what in 2018 in the US was a $3.6 trillion market. Palantir expects to hit $1 billion in revenue this year, built largely off the back of government contracts such as those it has with the HHS. Claims that this close working relationship constitutes an unprecedented merger of “Big Tech” and governmental bodies are inaccurate. To these corporations, coronavirus offers a perfect opportunity to establish a beachhead in public health — not in order to clear red tape or lend a helping hand, but to swallow up an untapped market. That they are not offering anything in the way of actual healthcare services (precisely as the miserable state of US healthcare continues to crater) is irrelevant. Digital contact tracing is not a health service, and does not replace or make efficient any existing public systems. It is merely another opportunity to realize profits. Corporations have no other impetus.

Though a few dissenting voices do exist, the prevailing tone among even critical accounts amounts to a sort of slack-jawed wonder at the possibility of demiurgic powers creating a new, pandemic-oriented technological apparatus “overnight”. Proponents accompany this awe with admonitions that we all do our part and heroically donate our data to the collective cause. Criticism, where it appears, often appeals to “liberty” and fears that individual privacy will suffer too much under the massive contact tracing regime to come. But it is not, as the LA Times puts it, a question of “lay[ing] the foundation for a potentially massive digital contact-tracing infrastructure.” That infrastructure is already here, and has been for decades.

Senator Ed Markey, who recently demanded transparency from facial recognition company Clearview AI to disclose partners who bought their software in response to coronavirus, sounded the noble-sounding warning that “we can’t let the need for COVID contact tracing be used as cover … to build shadowy surveillance networks.” But this is absurd. Clearview is not selling the promise of a future network to its clients — it is pushing a fully operational system, one which most recently has been deployed in Minneapolis to identify protesters. Speculation that digital contact tracing will spawn unprecedented surveillance practices a studied ignorance of the fact that these systems are already everywhere (and constitute a $45.5 billion market), the product of an decades-long and often hidden program of technological accumulation which we are at last beginning to see in their full and terrifying majesty. Many of these digital contact tracing infrastructures were originally developed for applications of counterterrorism, law enforcement, or corporate security, to name a few. These same systems are now being also sold as tools to detect isolated individuals and predict outbreaks, accompanied by a rebranding and the abandonment of military aestheticization and purpose for the adoption of a more compassionate posture. We are meant to understand that surveillance is no longer the god-cop but the god-doctor, when in reality it wears whatever mask necessary in order to expand its remit and collapse discrete theaters of operations into a single, vast datascape.

There’s a tendency to treat these systems as if they’re as “ephemeral” as the data they generate, only occasionally given form in conspicuous cameras, “benign” Ring doorbells, or facilities like NSA’s TITANPOINTE ops center in Manhattan. The reality is that urban space in general is riven with sensorial capacities. Cities across the United States, large and small, already employ an arsenal of systems which fall under the umbrella of “urban analytics”. Marshalling users’ phones, a network of sensing products, or both, urban analytics services offer “smartness” in marketing materials, which usually translates into an increased capacity for enforcement on the ground. There are no shortage of “Video Surveillance as a Service” (VSaaS) options available for the forward-thinking city official, running the gamut from products which overhaul existing camera grids — as in Arxys Appliances’ “City-Wide Video Surveillance” system for McAllen, Texas — to new age “smart” systems like Numina’s test cases in Las Vegas’ “Innovation District“and the Brooklyn Greenway. The most public-facing and savvy of these systems adopt design principles intended to present as approachable apps, while others lie in technocratic, specialist repose, offering no-nonsense datasheets of raw info. Regardless, the intent is punitive first, and everything else a distant second. These systems studiously attempt to pass themselves off as apolitical, draping themselves in wonkish and forgettably pleasant rhetoric about “solutions”.

What surveillance has always offered is the quality of feeling safe — “security theater” as a way of life — and coronavirus simply offers yet another valence of safety achieved through the addition of technology. This is the dream of “smart cities” realized: finally, sufficient technological investment is remade into a method by which to impose an impenetrable system of rational control onto the chaotic reality of everyday life without anyone noticing. Or, put another way, at the core of the smart city dream is the realization by those in power that urban warfare is easier to win not only by rushing the field with military hardware and legions of cop-soldiers, but also by preemptively modifying urban space itself so at all times it is a readymade battlefield, a universe of precision. It is not hard to see, nestled within overt presentations of luxury-predictive algorithms, that in the event of a crisis or emergency, that same ability to track, quantify, and adapt can quickly become the tip of the spear of military power. Every facet of life has been made quantifiable in order to make this all possible. The effect is not a “digital panopticon” (yawn), but something more akin to the Jesuit redução communities of colonial Portugal, in which streets were built elevated in order to allow the colonizers to look in through the windows of private residences. Fundamental is the extension and diffusion of power, until it becomes easy to ignore because it’s just the “way things are”. But as dull and avoidable as it is, the violence it wields is effortless and capricious; targeted individuals and malign behaviors can be identified and dealt with with callous ease. The effect is, in many ways, a permanent occupation — by a force with not only overwhelming firepower, but which selects the terms and environment of engagement.

This is by no means a new development, as breathless commentators on the age of “surveillance capitalism” repeatedly attest. The first factories were spaces under surveillance, as were colonial holdings, and the tactic was absolutely essential in maintaining slavery at every stage, from ship’s hold to plantation. Dilating on surveillance in its present form presents it as a temporary aberration which has thrown us off the historical path to freedom, when in reality, it is a well-practiced tactic that has simply reached a new stage of development.

The metabolism of surveillance historically similar to that of war: in the interest of protecting property, innovation is achieved through the use of technical artifice to turn money into as much firepower as possible. The timescale for innovation is historical; as Amazon’s one-year moratorium on facial recognition technology attests, it can afford to wait, knowing the game is rigged in favor of its passive accumulation of force. Peace of mind has always been a commodity, whether you’re hiring Pinkertons or installing biometric sensors at the door to your apartment complex. Spatial surveillance perfectly unites technological development with authority, locking the two into a complementary union.

Look to security company Cellebrite, which is plugging its hacking software, usually used by police to gain access to locked iPhones and extract location data, as a method of limiting the movement of coronavirus infected individuals; the Israeli counterterrorism unit Shin Bet has turned its data registries over to tracking coronavirus cases; and the same data suites Palantir has sold to the HHS are (famously) also in use by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Likewise, landing.ai and Amazon’s infrared cameras are secondarily technologies to enforce social distancing and primarily workplace surveillance suites, but are being developed with an eye on integration in public space, as landing.ai’s recent demo shows. Critiques warning that digital contact tracing threatens to “turn the US into a surveillance state” are saying far too little, far too late. Nearly every state is already a surveillance state — coronavirus merely adds a mandate and a smattering of new terminology. Even the phrase “contact tracing”, a newcomer in the public lexicon, has already seen itself pressed into service as a method of identifying and tracking protesters, used by none other than the DEA.

So what of all of us, trapped in this diabolical, all-seeing machine? Even now, as the pandemic exploits the weaknesses of states and institutions, and before new political structures (designed to help some live with a coronavirus which never ends) coalesce fully around existing technological ones, hope in “restarting” has slowly resigned itself to an incremental approach or else none at all. Surveillance — or, to be more abstract, technology in general — has, in the messianic way traditional of Silicon Valley, been offered as a readymade fix to a problem. In actuality, all that has been achieved is the spectacle of disease control. Focusing on contact tracing sidesteps the brutal fact that confirmed infection is not the end, but the beginning of a torturous journey through a failing healthcare system — and even the possibility of testing is a privilege which can be wrested away. At the end of the day, technological contrivances are proposed in order to put a bandaid on a bullet wound. But technological artifacts never cured anyone on their own, and the crusade of smart city logic into the public health sphere is at best a pharmakon: a disastrous cure.

Digital contact tracing will not change the fact that the road to the “post-corona” promised land will be paved in bodies. If these sacrifices have any value at all, it is only as an offering to the capitalist Moloch — that is, only because they let the rest of us eke our way along, day after day, drawing nearer to the moment when it is demanded we exit quarantine and are made to return to whatever work remains in a world suffering from what Mike Davis has called “the arrival of something worse than barbarism.”

Cover illustration by Kevin Rogan, based on Herbert Bayer’s photomontage “Lonely Metropolitan” (1932).