There’s a welcome familiarity to be found in the bright lights, sticky floors, and questionable decisions made in a gay bar. Championing their status as a backbone of the LGBTQ+ community, gay bars began their journey hidden away in marginal areas of the city, providing a secret and safe space for people with same sex-orientations and gender-variant identities to socialise and openly express themselves. Eventually becoming a ubiquitous part of the fabric of many cities, they have since been celebrated as a beacon of progressive values, and even marketed by municipalities as an attraction to outside visitors.

In the past decade however, a wave of transformations within LGBTQ+ culture have altered queer social space beyond recognition. One of these developments is the availability of digital platforms such as Grindr, introduced across mobile devices in 2009. These apps offer their users efficiently arranged hookups with the same convenience that one might order a taxi or take-away, allowing these encounters to happen away from public view. With 3.8 million daily active users, Grindr’s popularity is evident. But after decades of queer visibility increasing in the public realm, it is important to question whether digital interactions can live up to the rich history that has been cultivated in the spaces between darkrooms and dancefloors.

Such a digital addition to the culture comes at a time of huge threats to the existence of queer space. Even prior to the coronavirus lockdowns, it has been well documented that gay bars have been closing at an alarming rate across Europe and North America — London alone lost over half of its LGBTQ+ venues over the last decade, while San Francisco’s last remaining lesbian bar closed its doors in 2015. While many critics have been quick to blame these closures on the rise of the aforementioned apps, there are a number of more complex factors at play. Shifting attitudes towards some members of the LGBTQ+ community in recent years have led to more assimilation and acceptance in many parts of the world, and therefore changed the habits of a number of queer people. Those with more assimilationist leanings would argue that with legal equality brought about by the advent of gay marriage there is no longer a need for venues specifically catering towards LGBTQ+ clients. But this fails to take into account the diversity of needs within the broader LGBTQ+ community. The reality is that while a young, white, cisgendered, gay man may have the privilege to drink anywhere, there are a number of more marginalised queer people for whom these spaces still provide a vital safe space and support network.

Cultural and technological shifts may have changed the social habits of some LGBTQ+ people, but the overall role these have played in the closure of gay bars is negligible when compared to the unwavering hand of the property industry. The reality is, many venues can no longer afford to pay their rent. Gay people, so the cliché goes, have often been among the first to gentrify inner city neighbourhoods – it is therefore ironic that queer communities, among other minority groups, are very much the subjects of this process. As Sarah Schulman stated in The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, gentrification “replaces most people’s experience with the perceptions of the privileged, and calls that a reality.”

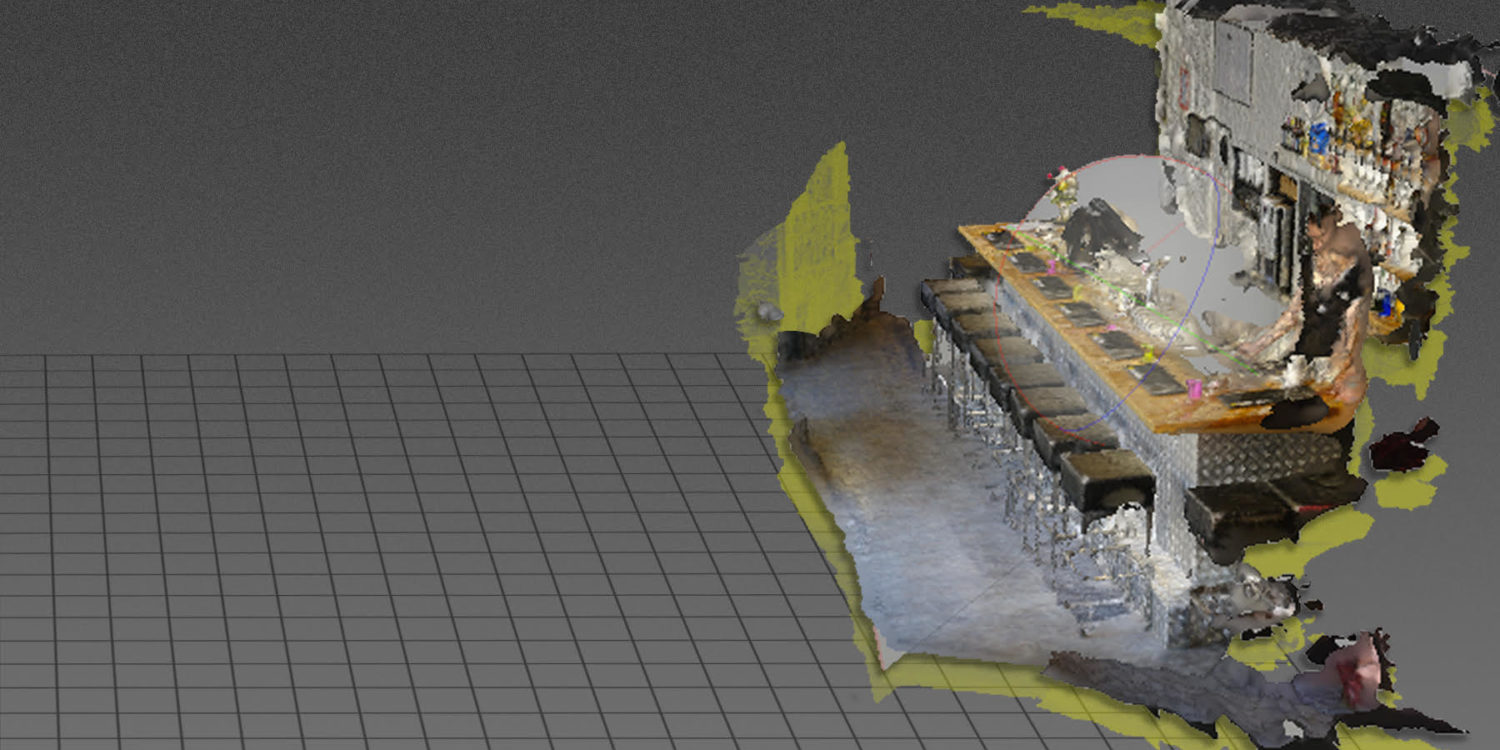

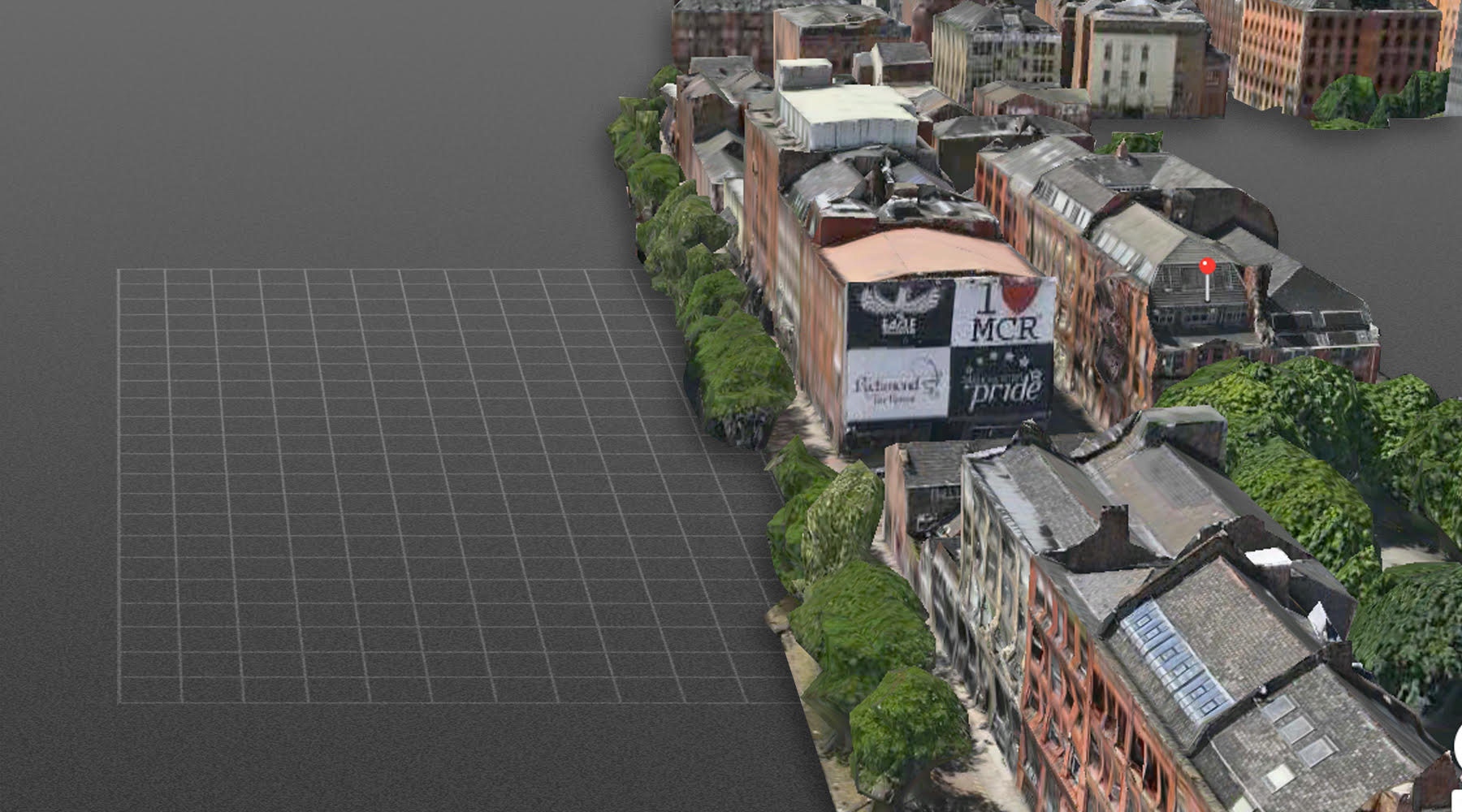

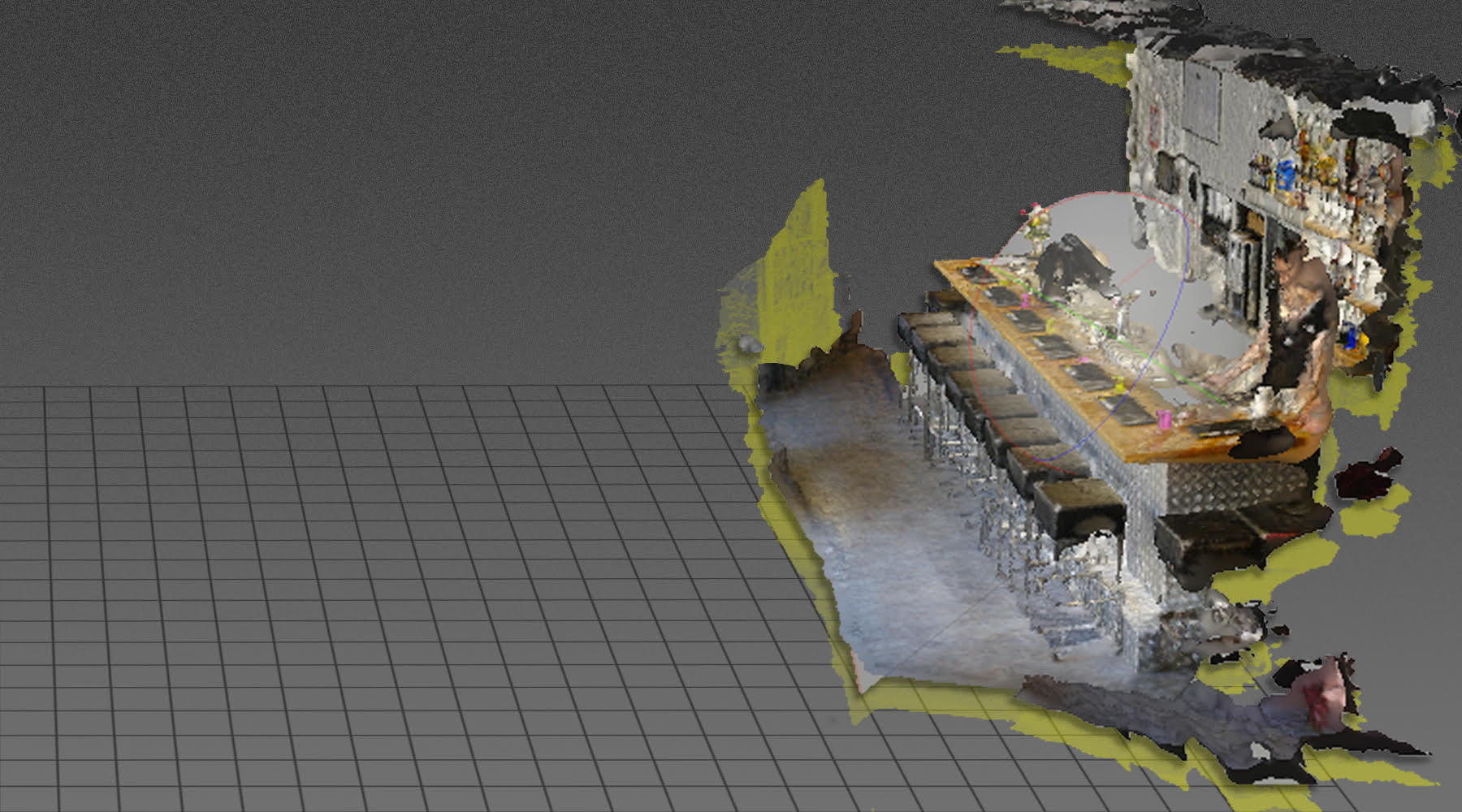

As a result, local authorities prioritise the concerns of newer, more affluent residents over those who may have originally formed a community in a given area. For example, a controversial 2018 regeneration masterplan for Manchester’s “Gay Village” – an area once proudly marketed as a spectacle of the city’s post-industrial cosmopolitanism – sought to re-brand it under the more palatable name of “Portland Street Village”. Although this attempted erasure was later put down to an ‘administrative error’ by the Council, they also announced that for the first time in its 30 year history Manchester Pride would happen outside of the gay village. With a wave of new property developments happening in the area, there simply wasn’t enough space left to host Pride in the village, so the annual event became an inaccessibly pricey off-site festival.

While Pride events increasingly bend towards sponsorships from large corporations to pinkwash their credentials, it must not be forgotten that such events have their roots in a riot that responded directly to police brutality in the late 1960s. Initiated to a great extent by trans women of colour, the event that is often proclaimed to be the birth of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement centered around the now infamous queer venue of New York’s Stonewall Inn. Visibility is important, and much of the progress made since would not have happened without this physical presence.

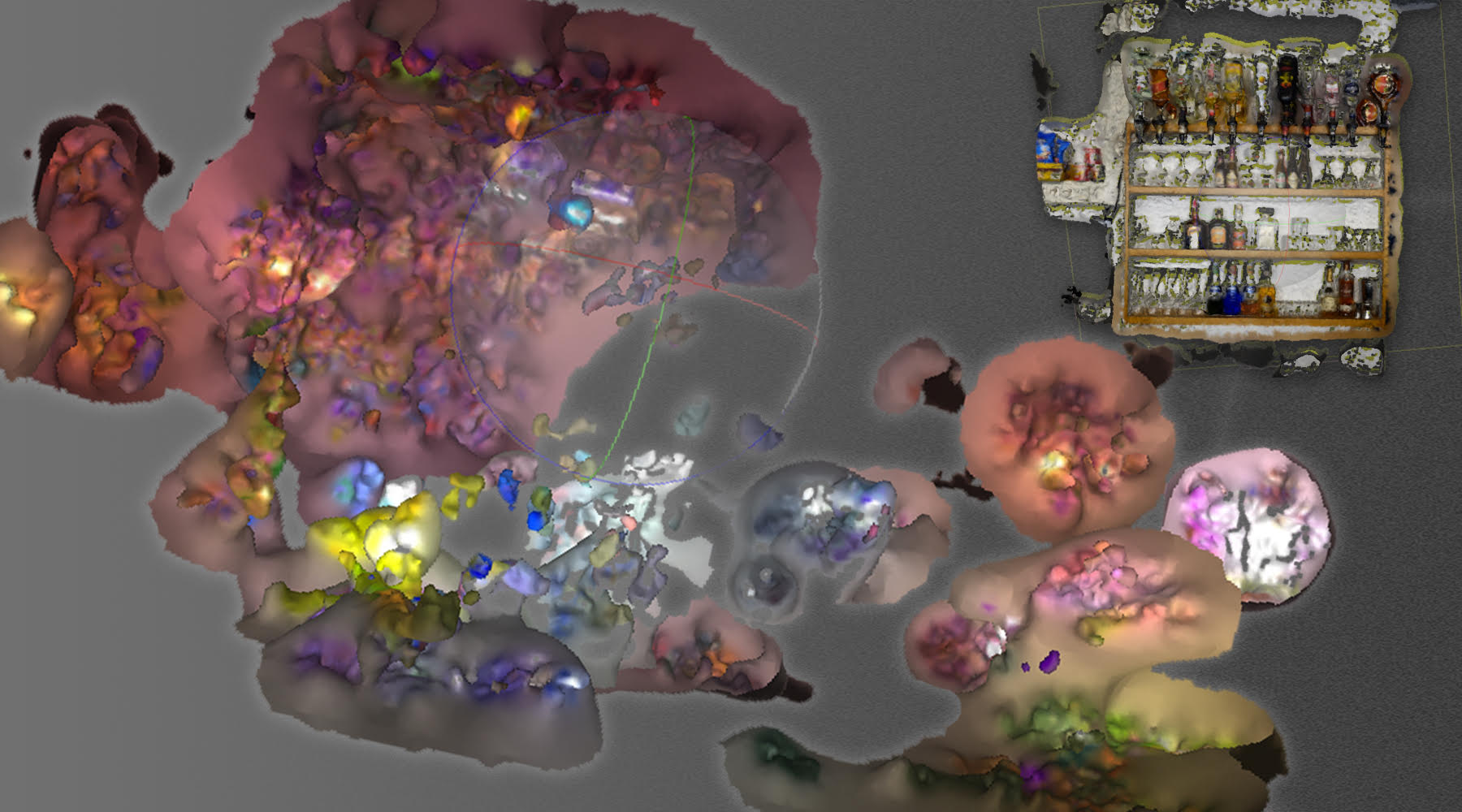

While queer spaces haven’t been completely erased from our cities yet, it is important to speculate on what is available to fill the cultural voids left behind by their depletion. In the contemporary city, digital platforms can be used to mediate most interactions between users and their physical environment. Locative geosocial apps such as Grindr and Hornet show the proximity of other users to the nearest metre, allowing strangers to connect to those nearby. This online marketplace allows for hookups to be arranged nearly instantaneously, after a short transaction of exchanging pictures, preferences, and pinpointed locations. The contemporary counterpart to cruising has benefits for many of its users — the convenience, discretion and comfort, fall in line with how smooth user interfaces permeate so many other aspects of urban life. From the perspective of the city authorities too, such encounters being initiated from the private realm of the home removes any seediness associated with sexualised public spaces. But this only addresses one aspect of queer culture and primarily caters towards gay and bisexual men.

This isn’t to deny that a primary function of gay bars has always been to facilitate sexual encounters – they’ve quite rightly provided a safe space for exploration. But while sex has played a large role in their existence, there is equally a sublime sense of community solidarity imbued in their walls. This became particularly vital at the most challenging of times, notably throughout the AIDS crisis years of the mid 1980s, or in the mobilisation against Margaret Thatcher’s Section 28 Law in the same decade. This solidarity has in turn extended towards other marginalised groups, such as the infamous ‘Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners’ campaign, or with the present intersections between LGBTQ+ liberation and racial equality. It would be a concerning movement then, for a digital platform to facilitate the spatial fragmentation of community. If encounters between LGBTQ+ people are now more likely to happen from a network of interconnected bedrooms than in communal spaces, queer people ironically retreat back, behind the screen and into the closet, reversing decades of activists fighting for visibility. Moreover, queer space is completely depoliticised when a once vibrant culture is mediated by a private technology company and flattened to the surface of a smartphone.

Important questions of privacy also come into play when a community’s interactions move online. Particularly in the case of dating apps used by LGBTQ+ people, there is incredibly sensitive data being entrusted to a privately owned technology company. Grindr has for a long time adopted a remarkably progressive policy regarding users’ HIV status, encouraging users to share it on their profile, thereby reducing stigma while encouraging regular HIV testing. Now consider the sense of betrayal when, in April 2018, it was revealed that Grindr had been leaking users’ HIV statuses to third party corporations. In an age where people are more acutely aware of how much information they are willing to share online, it would be a shame if this lack of trust in a company would cause users to retreat backwards from this progress. Moreover, the location data entrusted to the app can be highly sensitive, as the exact position of a user can be pinpointed by simply triangulating the distance between others. This is particularly dangerous in countries such as Egypt and Iran, where it has been reported that Grindr has been used by police to track down gay men to be arrested.

While the efficiency of these apps undoubtedly provides many benefits for their users, the question remains as to whether the adoption of digital interfaces can substitute the sense of community fostered by physical social spaces. In an essay in the 1996 book Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, George Chauncey wrote that “there is no queer space; there are only spaces used by queers or put to queer use”. Perhaps then, the nature of queer space can be seen as a moveable feast, adapting to the changing nature of our spatial environments. With so many interactions with the city now mediated by network technologies, the notion of digital platform-based queer space was inevitable. Recent circumstances have proven that this prospect is not entirely gloomy: as dancefloors across the world have closed as part of COVID-19 quarantine measures, a glimmer of salvation emerged with the unexpected arrival of online queer clubbing.

Subverting the intended use of the ubiquitous business conference calling platform Zoom, Club Quarantine hosted over fifty consecutive nights of DJ sets, performances, and defiantly queer entertainment, allowing for hundreds of visitors to virtually escape the confines of their homes each night. Although intended to bridge a gap while physical queer clubs closed due to the pandemic, Club Quarantine has been able to connect those who might not be able to access such physical spaces otherwise – young queer people living with their parents, people in rural areas, those with a disability who might have trouble accessing a nightclub, and those who would prefer to avoid alcohol. Additionally, unlike many platforms designed solely around sex and dating, Club Quarantine is not confined by physical proximity. In many senses, this network spawned by COVID-19 is altogether more accessable than many physical queer spaces. If trends such as this are to continue beyond lockdown, there would be a hint of irony that once again, LGBTQ+ culture will have been vastly reconfigured by a pandemic.

Queer spaces, in all their iterations, occupy a unique position in our cities. They have laid the foundations for groundbreaking activism, provided a platform for self expression, the construction of new identities, and given rise to an unfaltering sense of community. But the reality of their diminishing presence cannot be ignored. In the aftermath of COVID-19, who knows how many more gay bars will have been lost. In addition to this, existing alongside digital platforms is an inescapable reality. Platforms such as Grindr do attempt to fulfill a need around dating and sex, meanwhile Club Quarantine has suceeded in throwing much lauded worldwide parties. But is there a singular spatial or digital typology that caters to all? Has there ever been? Perhaps to conceptualise the idea of the gay bar as a utopia, would be a dangerous act of historical romanticisation – no space has ever been entirely immune to the structurally ingrained social inequalities of our society.

Nonetheless, one thing is certain: queer space can be considered as the direct antithesis to the heavily controlled and scripted realm of the neoliberal city. We must therefore fight for the survival of the radical potential of queer space – whichever form this might take. If its next iteration is mediated by the smooth surface of the screen, we cannot let this detract from what once made the gay bar so special.