At the industrial edges of Luxembourg sits a warehouse, discreet and servile to its surroundings. It is high-security modernism materialised. Within this mass of concrete purportedly exists an economic model for a future Britain outside the EU customs union. Its name is Le Freeport, one of several global complexes affiliated with notorious art dealer and “freeport king” Yves Bouvier. Obscured by both its economic make-up and physical architecture, it conceals the largest yet most classified hoard of paintings, cars, wine and other luxury items in all its tax-free solace. Gilded in mystery, Le Freeport embodies architecture’s increasing role as a tool of exclusion: erecting walls, drawing borders, reinforcing barriers.

Like its namesake, Le Freeport is “a port area where goods are exempt from customs duty”. The contemporary resurgence of freeports has until now been quietly established within the economy of luxury goods, investment procurement and business, attracting a multitude of companies due to the lower regulations they facilitate. Some are inaccessible sites containing unfathomable art collections, others are fairly banal business complexes often located in or near airports, ports and other sites ulterior to an everyday city dweller. However, they often share a discrete exterior architecture, demonstrative of the consistently murky operations inside.

Beyond their architectural subtlety, a firestorm of reports have explicitly associated these sites with tax evasion, curtailment of money-laundering laws and, even, terrorist operations. Their reputation precedes them. And yet, since the beginning of Brexit negotiations, the UK’s Conservative Government has been working on plans for up to ten, “supercharged” tax-free economic zones across the country, according to Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

This comes as part of the government’s post-Brexit “levelling up” strategy, which intends to bring the economies of regions beyond London up to speed with the capital. Notwithstanding the fact that these freeports come nowhere near to redressing the country’s deep structural imbalances, they also essentially double-down on globalised free-market policies that created these imbalances in the first place. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the wider economic context could not have been less auspicious for a national policy focusing on global free trade. As writer Richard Seymour explained in a recent Patreon essay, the pandemic “has just turbo-charged deglobalisation.” Thanks to the fragility of long-range just-in-time supply chains, “trading systems are likely to be regionalised… a long-term trend exacerbated by COVID-19 – rather than globalised further.” In short, these freeports provide a potent symbol of the various contradictions that characterise the UK’s contemporary political economy.

Centuries before their current iteration, the freeport’s presence was already inextricably tied to special privileges and tax breaks on items such as tobacco and alcohol: from medieval Cinque Ports in southern England and along the port cities that comprised the Northern European Hanseatic League, to bonded warehouses in the 19th century. They reemerged during the modern era in 1956, in the small town of Shannon on the west coast of the Republic of Ireland. The Shannon Free Zone (SFZ) gave over 100 companies special tax breaks if they operated within the 600 acre area.

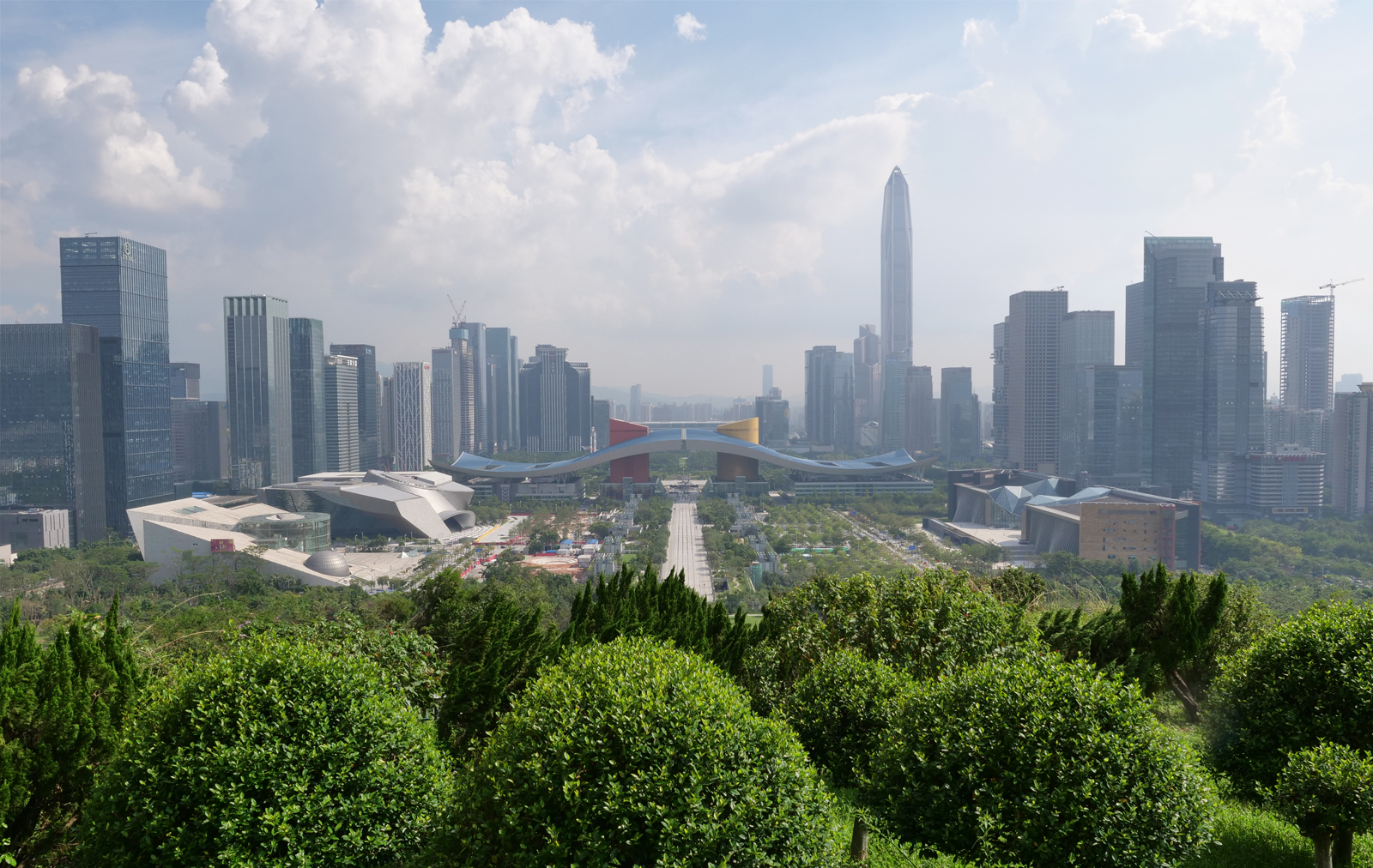

Just over three decades later, China under General Secretary Deng Xiaoping employed the freezone as part of its radical “Opening Up” strategy. The first of its Special Economic Zones (SEZ) was established in Shenzhen, which helped transform what was a collection of small fishing communities numbering no more than 30,000 into a city that has long since surpassed its neighbour Hong Kong in terms of both population and economic output. Allowing individual provinces and local municipalities to invest in industries they viewed as most profitable, Deng’s so-called “market socialism” radically transformed the country, creating millions of jobs for communities in rural towns and villages.

Futian CBD, Shenzhen in 1998, as viewed from Lianhuashan Park

wanghongliu/Wikimedia

Futian CBD in 2018 as viewed from Lianhuashan Park

Sparktour/Wikimedia

In 2018, Conservative Tees Valley Mayor, Ben Houchen, in collaboration with construction firm and consultants Mace Group, commissioned a report detailing a plan to create seven of these “supercharged” freeports across the UK’s Northern regions, in ports at Grimsby, Hull, Liverpool, Manchester Airport, Teesside and the Port of Tide. As with the Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) that emerged in the 1990s following the Thatcher era, freeports are packaged in the language of acceleration and economic solvency, yet centre on the increasing privatisation of public space. As British writer and architectural historian Anna Minton argued in a 2006 publication What Kind of World Are we Building? The Privatisation of Public Space, written for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, BIDs are “sterile places which lack connection to the reality and diversity of the local environment” which pose drastic “effects on cohesion, battered by the creation of atomised enclaves of private space which displace social problems into neighbouring districts”.

In the same way, it is difficult to see how freeports benefit nearby communities considering that they are by definition “fenced enclaves for warehousing” of goods that are in “permanent transit”. In an article for Artsy, journalist Atossa Araxia Abrahamian, noted that local residents and neighbouring employees to a newly opened freeport in New York’s Harlem heard nothing of job opportunities, social improvements or the new local inhabitants (multi-million dollar artworks). Conveniently named ARCIS, or “fortress” in Latin, the US’s Foreign-Trade Zones Board granted this freeport, owned by real estate giant Cayre Equities, special economic zoning and $13 million in tax breaks based on job creation promises – all of which have gone unfulfilled. As Atossa explains in the article, “employment at art storage facilities typically goes to aspiring artists who know how to handle, crate, and transport the art, or employees with specialised skill sets similar to those of a museum registrar.” The freeports that house such valuables have also been the subject of interrogation and criticism within the art world, with artists such as Hito Steyerl coining the term “Duty Free Art”. Yet, their dubious nature has still largely evaded public consciousness.

The UK’s December 2019 general election delivered a sizable majority to Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party, including 106 new MPs into Parliament, several dozen of whom hail from constituencies in the North of England that had long been considered Labour Party strongholds. Johnson was quick to recognise that these seats were temporarily “on loan” to his party. In this context, freeports have emerged as a focal point of the government’s economic strategy for the coming years. Evidently, the need for a plan that appears to resolve the logic of Brexit while rebalancing wealth in favour of the “left behind” parts of England trumped the reality of a global economic situation which had already been moving against global free trade even before the pandemic.

With support from the aforementioned Mace report by construction firm and consultants Mace Group, Northern Conservative MP Simon Clarke went to parliament to claim that “if freeports in the UK were as successful as those in the US, we would create an additional 86,000 jobs”. Earlier this year, the UK’s Trade Union Congress outlined its concern over this projection in several key points. Specifically, workers in freeports are likely to have less security and protection than those in the rest of the UK, through lower pay and typical “gig worker” contracts. Furthermore, the TUC report highlights that the tax-free rupture in the UK’s economic system could lead to less money paid towards key social provisions, such as the NHS and education services.

The pervasive aesthetic of these sites often evokes what architecture critic Owen Hatherley calls a “pseudomodernism”: “a modernism of concealment, a stylistic shell left after all the original social and moral ideas have been stripped out”. In Luxembourg, Le Freeport sits adjacent to Luxembourg Findel Airport, with its very own internal road for transporting cargo straight off the runway. Comprising 6,400 cubic meters of concrete across four stories and spanning 22,000 square meters of land, its physical architecture is concealing, formidable and fortress-like. The exterior caged grey stone walls, excavated from the local site before construction, encase a configuration of strong rooms, vaults and safes that are kept at a consistent temperature of 21°C and 55% humidity. In a press release, Le Freeport’s architects 3BM3 Atelier D’Architecture provided an obscure caveat: “the legal requirements become an excuse for a volumetric game that breaks the banality of a simple box and creates formal tensions.” Superfluous language obscures the problematic function of the building: “volumetric games” and “formal tensions” masquerade legal formalities as artistic intention, while seemingly absolving the architects of any responsibility for what happens inside.

In February of this year, the UK government announced a consultation, which set out their freeport policy agenda and called for responses from relevant stakeholders. While the results will be shared later this year, we can already get a measure of the government’s thinking from the document’s ministerial foreword. Tellingly, the ministers seek to quantify its merit with reference to the Ancient World, where Greek and Roman ships were “piled high” with fine oils and wines. This overtly romanticised vision is grossly out of step with the current urgent and stark economic context. Instead, we can expect an architecture that speaks not of prosperity, job creation or economic rebalance, but of economic efficiency and concealment.