This article is part of the FA series “A City of Our Own: Urban Feminism for the 99%”.

Women navigate Pakistani urban space through various limitations set by social standards. While these limitations are gendered, socio-cultural, and religious, they are also reinforced by the built environment itself. The long-lasting effects of British colonisation on the social structures of the country can be observed in both the physical layout of cities and in the Pakistani home. Gated communities and suburban-style neighbourhoods, which have recently become so popular in the country, could not be further from its traditional urban organisation. Indeed, in their uniformity, these new residential areas manifestly fail to live up to the diverse experience of urban space that was once so common prior to British colonisation. In particular, the distinction between private and public is rigid and does not allow for in-between areas, varying degrees of privacy, and flexible uses.

The transition from traditional spatial configurations to Western ideals had a significant impact on women’s access to urban spaces. A closer look at this transition offers a useful glimpse into the role of architecture in legitimising women’s place in public environments or, on the other hand, in pushing them further back into the confines of their home.

Pakistan has a long architectural history, with its earliest known settlements dating back to 2300 BC. When the British invaded and colonised the Indian subcontinent, the country was mostly characterised by Indo-Islamic architecture (specifically Mughal Architecture) from the 16th until the 18th century, and some remnants from pre-Islamic era, mainly Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist temples. The period following independence brought with it an architectural style that is largely referred to as the “Post-Independence” style, a combination of all the preceding styles with modern architecture. This makes up the large bulk of today’s Pakistani architecture and is heavily inspired by globalised architecture.

Before British colonisation, the traditional subcontinental homes presented various architectural features that had been developed to respond to specific climate conditions as well as cultural traditions. One of the most influential cultural norms was the need for women to maintain a certain level of privacy, strongly reflected in the local architecture.

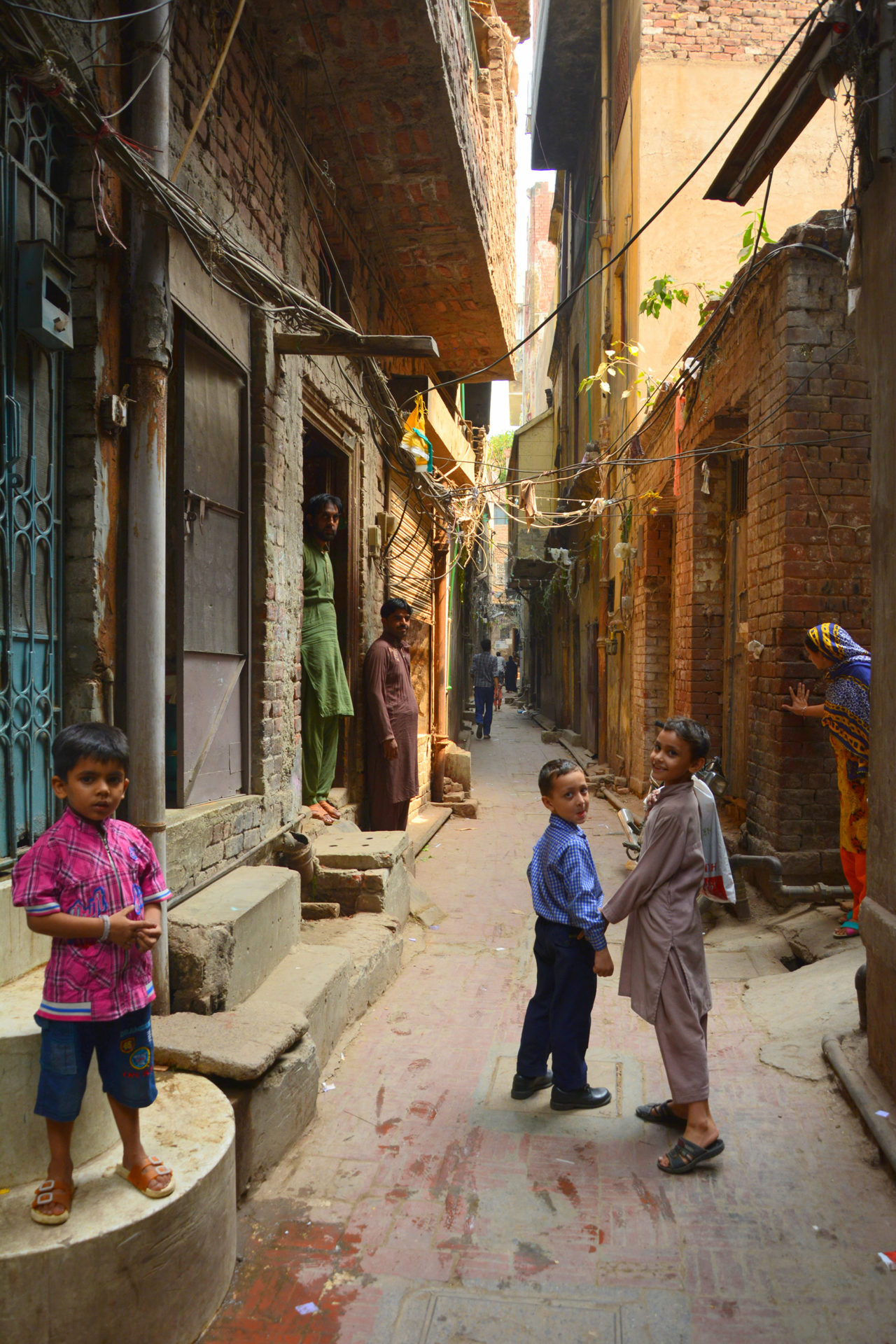

Today, the only surviving large-scale remnant of traditional housing and neighbourhoods in the country is Old Lahore, the historical core of the capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab. The city was formally established around 1000 CE and fortified by a mud wall during the medieval era. Today, the Old City serves as a standpoint from which to understand traditional Pakistani spatial elements, and the resulting social interactions they facilitated, especially regarding women’s presence in the urban sphere.

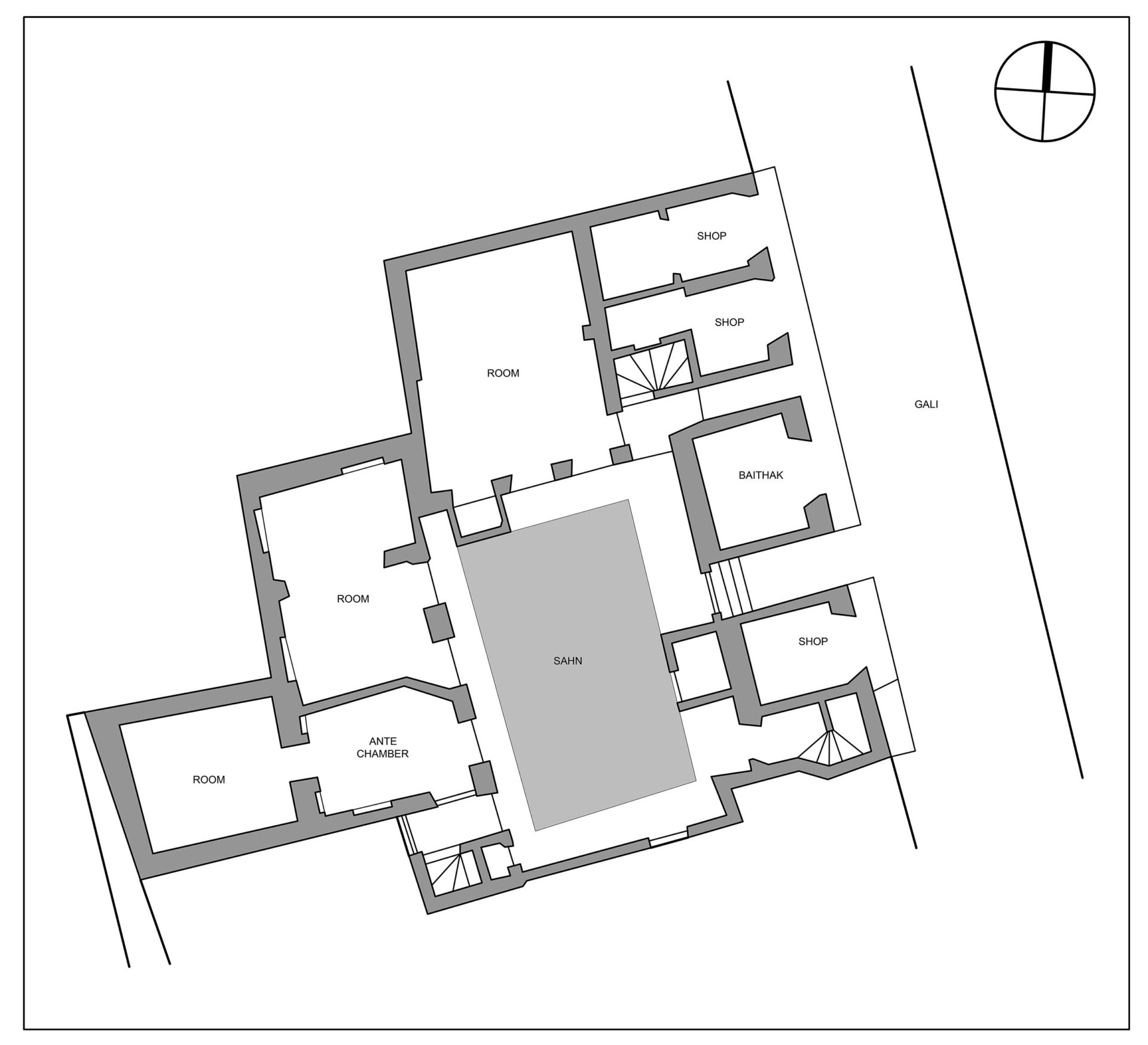

Old Lahore has a distinct street system based on a defined hierarchy of public, semi-public, and private spaces, which greatly influenced social structures. One of these key semi-public spaces is a communal courtyard known as sahn. Depending on the size of the sahn, the houses around it became part of a koocha, a small neighbourhood. These houses are the traditional residences of Old Lahore, the ghar, or in the instance of an ancestral mansion, the haveli.

Traditionally, the ghar, the home, is associated with the privacy of women, and the bahar, outside, is considered the public domain of men. Feminists have often focused on unhindered access to public space as a mark of gender equality. However, the public/private dichotomy has tended to be viewed from a strictly Western perspective. Yet, within Islamic culture, this demarcation is not as rigid – instead, the implications of public and private are predicated on the Islamic notion of mahram and na-mahram. In Islamic law, a mahram refers to any person with whom marriage is forbidden, either on account of blood-relations, marital ties, or breastfeeding. A na–mahram, by contrast, includes everyone that does not fall within the definition of a mahram. For practicing Muslim women, sharing space with na-mahram men becomes regulated, as it requires them to wear a veil. Thus, while spaces per se cannot be seen as inherently ‘public’ or ‘private’, it is the kind of interaction that takes place within that defines them. Places where one is more likely to interact with na-mahram then become the most restrictive spaces.

Since the neighbourhood around the sahn was structured as a semi-private space, the communal sahn led to an urban opportunity for the women to safely interact with one another in a public space outside their homes. Due to the height of the buildings surrounding it, the sahn offered a distinct feeling of enclosure and safety, a cultural requirement for women’s participation.

Upon entering the haveli, the typical house opening on the communal sahn, one would walk through a transitional space to a smaller, indoor sahn. This access was open during the daytime so anyone could walk into it from the public street, while during the night, the doors were closed so it became completely private. Thus, the sahn was the social center of the house, promoting maximum interaction for women due to its inherent openness, all within the privacy and safety of the home. The sahn acts therefore as a private-public space, especially for the women of the household; yet, women’s access can be restricted if the sahn is already occupied, depending on the level of conservativeness of the family. These spaces also aided in passively maintaining the indoor temperature, helping to cool the adjoining rooms during the hot summers and letting the low winter sunlight filter inside in winter.

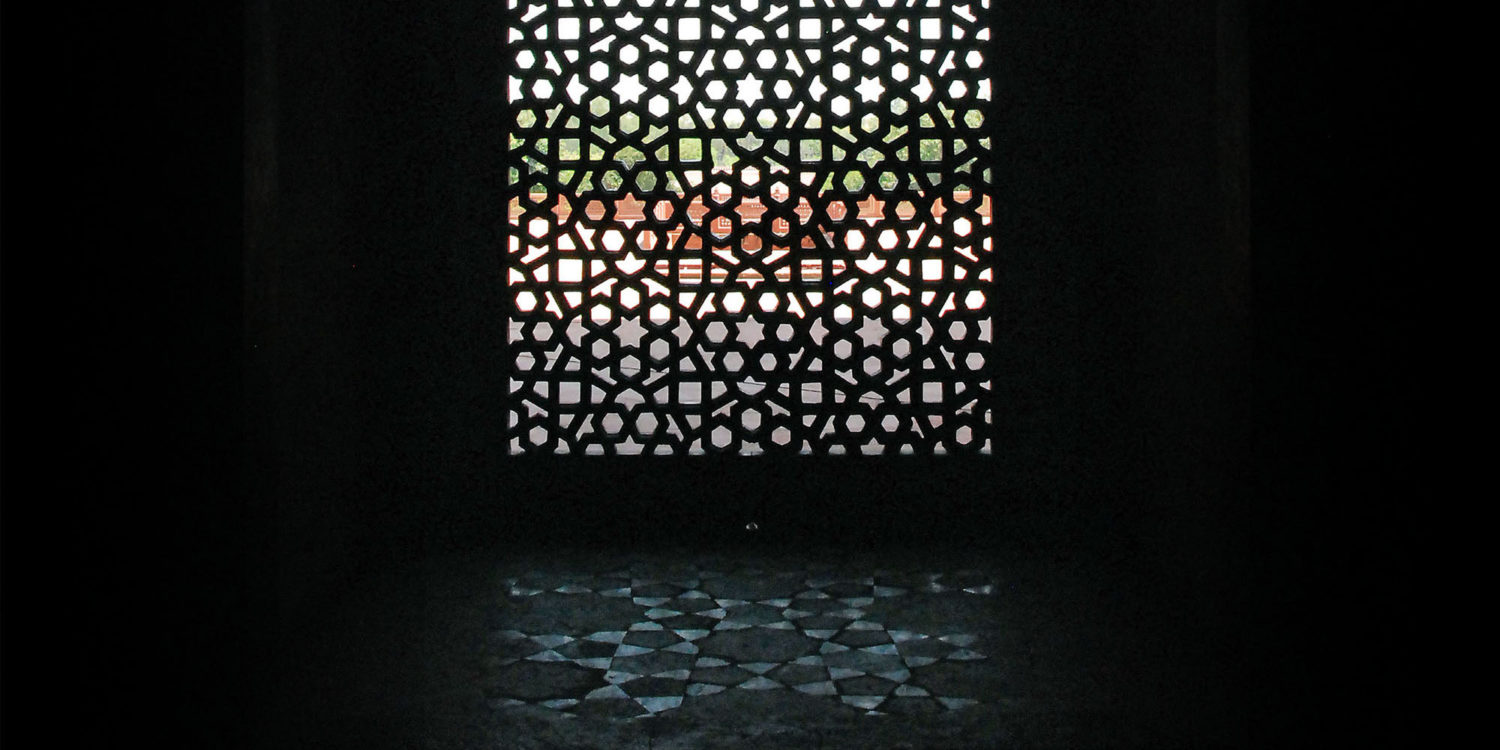

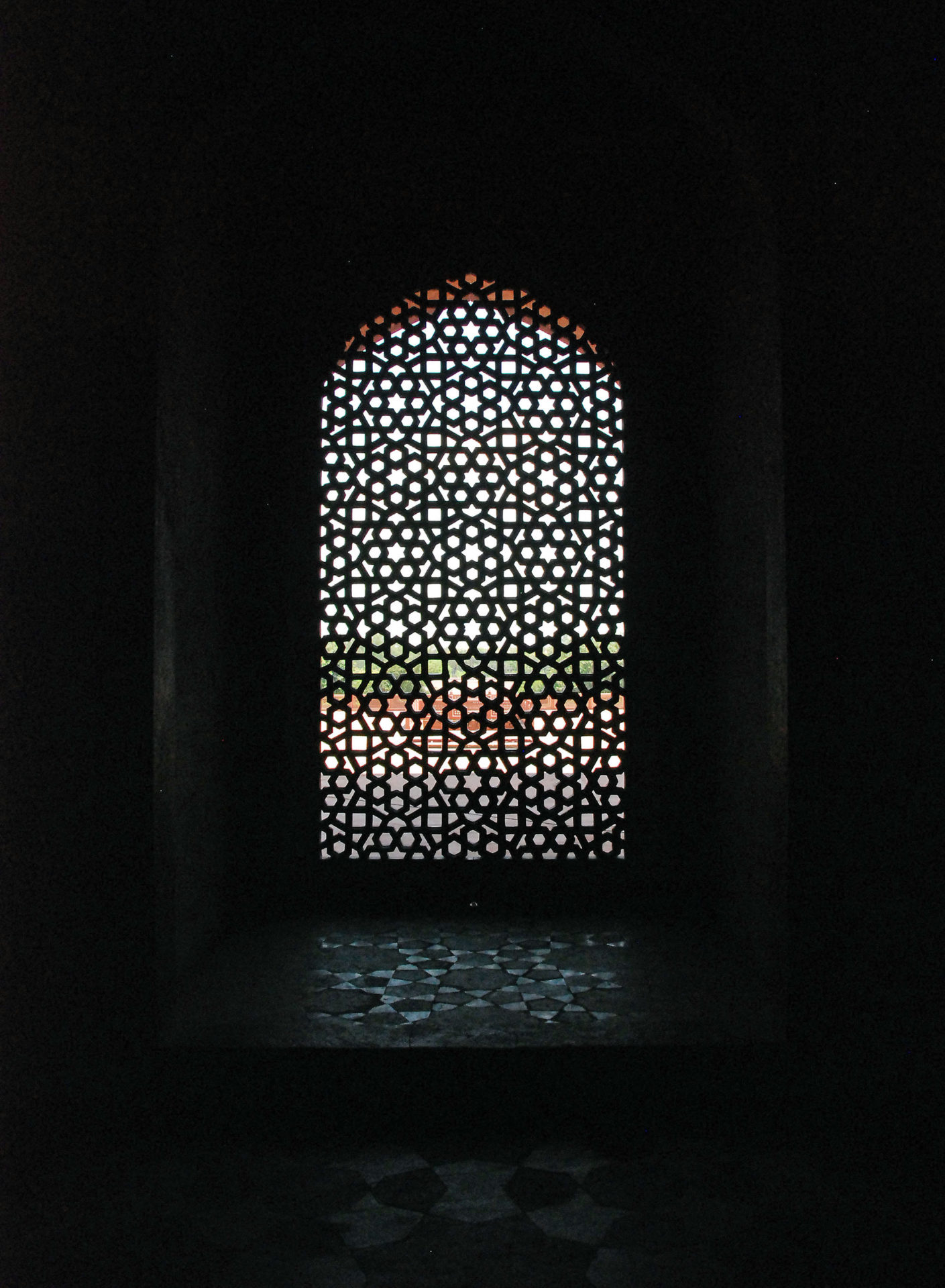

While environmental considerations were a major factor in the spatial composition of the traditional house, the individual components seem mostly designed to facilitate women’s engagement with the public domain. The influence of the veil ordinance on the traditional house is perhaps the most evident example. The jaali was a perforated screen that acted as a direct architectural representation of the veil. It allowed women physical privacy according to their cultural and religious requirements while granting them access to the urban sphere.

Thus, the jharoka, a projected window that utilised the jaali in its composition, became a defining element: it allowed women to interact with one another through neighbouring houses, as well as providing communication to the street below. As everyone knew one another in the neighbourhood, one could stand inside their jharoka and be connected to the outside—it was common for women to ask any of the kids playing downstairs to run errands.

Another important element that encouraged women’s engagement was the tharra, an extended platform in front of the house, which served as a sitting space and facilitated interaction with the neighbourhood at the street level. It was largely utilised by women; in particular, the neighbourhood streets became private for women when the men were at work or in the mosque. With the men gone, the women would socialise and visit each other freely. Within the confines of a neighbourhood, everyone knew each other, which made access for women not only simple but unrestricted. There was no limitation for women moving around because of the watchfulness of neighbours for one another: everyone would look after each other and women’s safety was assured.

As the floor levels moved up, the situation changed. The chhat, or roof, provided the maximum detachment from the sahn but granted contact with neighbouring houses and the street from above. As the street was the domain of men, the chhat became the domain of women, who would access each other’s homes through the interconnected mesh of chhats within the neighbourhood.

In can be argued that maintaining privacy is a reason for the jharoka no longer being a common element in the contemporary Pakistan home, but one of the major factors in changing the local architecture was the influence of British architecture. When the British colonised the subcontinent, vernacular architecture did not seem to satisfy their needs. While their presence was necessary to subjugate the locals, it was not considered prudent to adopt their ‘uncivilised’ dwellings: they were deemed too outlandish and generally inferior to the ornamental Late Georgian architecture that was the reigning style in England at the time. Additionally, the openness of the local house lacked the privacy and the exclusiveness of British residential architecture, resulting in British architecture and urban design making its way into the region.

As a consequence, most local architectural traditions were lost. It became common for locals to emulate the British in every way, as a means to elevate their social standing. The internalised self-hatred that stems from being colonised had rather dire consequences on local architectural design. Even long after Pakistani independence, contemporary architecture no longer utilises traditional elements. This has had not only a considerable negative impact in terms of designing environmentally responsive homes, but also a negative effect on women’s engagement with the bahar. By removing the jharoka from the façade of the traditional home, the women were physically and metaphorically pushed back into the confines of the house.

Although it can be argued that gender designated spaces in the traditional Pakistani home may have curbed women’s presence in the urban sphere by limiting them inside the ghar, it is also evident that the Old City configuration facilitated women’s engagement with the bahar. Women sitting within the comfort of their homes had a direct connection, both visual and auditory, to the bahar as well as to other women. In addition, the urban configuration allowed them to step out together and access bigger communal spaces like the communal sahn. Different spatial hierarchies allowed women to form intimate connections with each other and the bahar. As women’s safety tends to improve by traveling in numbers, for women it was fundamental to maintain an open interaction with neighbours in order to socialise and make connections, using each other’s presence to move into the broader urban sphere.

While traditional elements allowed greater participation for women, they also allowed for less privacy within the sanctity of the home. The traditional architectural elements entailed a certain degree of publicization of the private domain, as the privacy of the home was continually compromised.

Yet, traditional architectural elements were also great passive heating and cooling tools. In contemporary Pakistani homes, air-conditioners and heaters are needed to provide a consistent interior temperature. The need to isolate the interior space from the outside, by keeping doors and windows closed as much as possible, contributes to physically disconnecting inhabitants, women in particular, from the outside world.

With gated communities becoming ever more popular in Lahore, developers are meticulously planning new neighbourhoods with sometimes cookie-cutter houses, in contrast with the variety of the Old City. This has, unfortunately, caused a visible decline in the practice of cultural activities, festivities, and social activities that were strictly connected to the traditional architectural configurations and spatial functions of Pakistani cities. Prioritising a local iteration of suburban sprawl, Pakistan’s contemporary urban landscape lacks the opportunities previously provided to women. It accepts the heterosexual male body as its standard, creating gendered demarcations in access for anyone straying from this norm, including women, disabled people, the elderly, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Looking at traditional spatial elements designed to facilitate women’s engagement with the urban sphere, it’s possible to imagine how new residential neighbourhoods in Pakistan could benefit from incorporating old spatial principles such as urban pockets accessible to marginalized bodies.

While women’s access has been negatively impacted for several reasons such as the socio-cultural setup, religious beliefs, and the general patriarchal outlook of the people, architectural practice and urban design have been complicit in normalizing women’s unequal rights of access. Now, women are finally starting to challenge this spatial narrative. Local initiatives such as feminist collective Girls at Dhabas, stand-up comedy group Auratnaak, and Aurat March (Urdu for Women’s March) are normalising and legitimising women’s access by advocating for women’s rights, and encouraging them to engage with the public domain.

As the adoption of a generic approach to architecture and urban planning led by British colonialism has shown, simply adopting Western-style spatial configurations (perceived as not specifically gendered) is not enough. In fact, it has revoked the degree of movement, connectivity, and independence offered by traditional elements of Pakistani architecture. With the disappearance of the chhat, the jharoka, and the sahn, women and other marginalised bodies have been pushed deeper into the privacy of the ghar, rendering them invisible and reinforcing the notion that the bahar is the exclusive domain of the heterosexual male. In order for this erasure to be reversed, our cities must be reimagined. For the built environment to become a tool to resolve gender disparities, it is necessary that architects and other professionals adopt a gender-sensitive approach that takes into consideration cultural and social norms and traditions.