‘El mejor anuncio de la historia’, or ‘the best ad in history’ is a picture taken in February 2008, which neatly encapsulates several aspects of the city’s urban landscape: the formal, the informal and the promotional.

At the time it was taken, 54% of Caraqueños (as the inhabitants of Caracas are called) lived in ranchos such as those featured in the top half of the image. Ranchos are the forms of informal housing that cover the hills surrounding the city. Clusters of self-built ranchos form larger neighbourhoods referred to as barrios – similar to the Brazilian favelas.

Meanwhile, in the lower half of the picture, beneath the ranchos, lie the more formal infrastructural elements of the city. Both the highway and the tunnel were completed in the 1950s, a decade which saw Venezuela’s most significant modern transformations, most notably in mass housing and infrastructure.

Besides the sharp contrast between the formal and the informal in Caracas, propaganda and advertising are another crucial element in the city’s landscape. Large political or commercial posters are mostly added to the city’s tall buildings which dot Caracas’ verdant valley.

The advertisement featuring in the landscape of El mejor anuncio en la historia is unique as it covers an entire block of informal dwellings, tying them together in a single promotion for Maggi. In this rare instance the promotional acts to draw the informal closer to the formal, providing us with an insight into the fitful history of the city’s development and conveying an intended modernity which was never properly consummated in Caracas.

The Black-Golden Age

In the 1950s, Venezuela struck black gold. Overnight, it went from an insignificant Spanish post-colony to a country promising modernity and opportunity. During this period, the government of President Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952-58) carried out their principal improvements to the country\s physical environment.

Under the Nuevo Ideal Nacional (New National Ideal), the country was completely reorganised. Highways and other infrastructural projects made way for industrial conglomerates and multinationals, setting an example for modernisation in Latin America. Venezuela developed into a nation of consumption and in the process the visual identity of Caracas became ever more reflected in the excess of advertisement. All the while, international influence on the economy started to translate into international influence on society.

Filled with optimism at what a new life in Caracas could offer, thousands left the countryside to seek their fortune in the big city. Accommodation had to be arranged for the new inhabitants and inspired by Le Corbusier’s Cité radieuse, massive housing units were designed and built to host the new citizens, 23 de Enero becoming the most famous of these so-called superbloques.

However, the housing solutions provided by the government could not keep up with the rapid rural exodus. Besides, the housing units increasingly failed to meet the ambitious expectations of the original plan, proved too segregated and often developed into dangerous no-go areas. Little by little, waves of ranchos engulfed the hills surrounding the Caracas valley. Creating their own informal settlements, the citizens expressed their dissatisfaction with the inadequate policies of the country’s politicians in the only way they knew how.

As Justin McGuirk, author of Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture, comments: ‘From all its bravura, Latin America is where modernist Utopia went to die. Today, 23 de Enero is paradigmatic of the problems that beset this ambitious and single-minded vision of mass housing. Crime ridden and overcrowded, it is a viral law unto itself, a place where the police seldom go if they can help it. Around and in between the super bloques a carpet of slums has grown, an organism that now seems to bind the blocks together in some symbiotic relationship. These are the kind of hybrid forms that are developing in Latin American cities, where the rational vision of the mid twentieth century is giving way to the ineluctable logic of the informal city.’

Pejoratively dismissed as ‘slums’, these informal cities tend to be associated with criminality, but they also carry another message. With a minimum of resources and a collaborative approach people build their own homes according to what best suits their needs. Building the ranchos is a highly social activity in which local materials are applied in ingenious ways. The community builds its ranchos on a healthy diet of shared knowledge and mutual aid. Independent of the professional intervention of architects or urbanists, those low-income citizens who were excluded from the super bloques have actively made their mark on the city’s built environment, spreading the ranchos all over the hills and developing tight communities in their barrios.

For an understanding of Caracas and its built environment, the ranchos that cover the hills of Caracas clearly provide a rich vein of insight into life in the capital. But this form of settlement has now gone beyond its natural context and spilled over into the city’s tallest building. This more recent development suggests that these informal units have the unusual ability to transcend typical housing typologies.

The vertical barrio

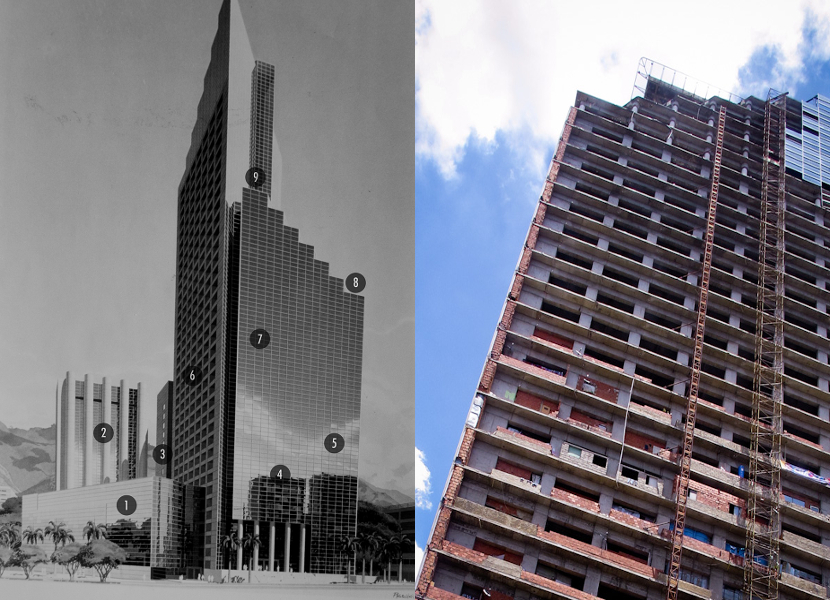

Torre de David was originally designed to be the tallest building of a wealthy city, providing the headquarters for the Centro Financiero Confinanzas, the country’s biggest financial company. Between 1990 and 1995 Venezuela remained the Latin American country with the highest (registered) income per capita. But these records did not reflect the reality of growing poverty.

A moment that unmistakably marked the decline of wealth was the bankruptcy of Centro Financiero Confinanzas. Torre de David, the skyscraper that promised to be a modernising project and symbol of economic power, was abandoned unfinished.

From that moment, Torre de David began to serve as a perfect articulation of the wider socio-economic situation. In 2007, large groups of poor individuals and low-income families affected by the housing crisis in the country carried out an illegal occupation of the structure, at the time aided by a law which stipulated that any unoccupied building could be taken up as a residence.

The way the Tower was inhabited bears a great resemblance to the mass occupation of the hills around Caracas after the economic boom. So too does its reconstruction by the new inhabitants: rancho house-types were built inside the Tower, using the same bricks and types of windows. During this period, the inhabitants of Torre de David mimicked the organic life in the barrios.

From a dilapidated ruin, Torre de David was born again as the home and indeed working space for 1156 families. In August 2012, the Venice Biennale of Architecture awarded the Golden Lion award to the Torre David / Gran Horizonte presentation. The building’s inhabitants did not receive the prize, but they certainly got attention. Maybe too much attention, since in July 2014, the government initiated a process of relocation of all its inhabitants.

Housing Solution: The main message

Moving such a large group of people meant the implementation of a wide-ranging governmental strategy. The relocation of the Torre de David inhabitants was included in the Gran Misión Vivienda (Big Housing Mission). Started in 2011 by Hugo Chavez, this plan had already emerged to try and solve the continuing housing problem of Caracas. It should come as no surprise that such a grandiose and top-down strategy bore striking similarities to the earlier super bloques solution applied in 1953. Again, huge buildings containing multifamily units have been built all over the country, some of them on prime locations in Caracas, while some have ironically been settled next to already established barrios, further from the urban centre. En masse, the idea of home and communal integration is once again being forced upon large groups of people by governmental planning.

In a predictably short space of time the Gran Misión Vivienda constructions have gained notoriety as conspicuously dangerous places, much like the super bloques that came to ghettoise the population 60 years before. And so people keep going back to the reliable autonomy of the barrios model, and construction of ranchos continues unabated. It’s a fact that seems to have eluded the government, who are clearly yet to consider them a final solution.

All this is a shame because the bottom-up housing revolution that has organically presented itself over the years could be more than a temporary expression of poverty. Even more excitingly, it could be seen as an attempt to develop a specifically Latin-American housing prototype.

All these years, caraqueños have expressed a spontaneous manifestation of urban development through their dwellings. Over a period of more than 60 years their efforts have shaped the habits of a large community. At this moment, the previous inhabitants of Torre de David are being moved to a Misión Vivienda project, outside of the city. Meanwhile, Torre de David remains a mark of Venezuelan times, lacking a clear purpose, and sporting the biggest political poster in the country.

Venezuelan politicians are still exploring ways around these problems, ignoring the answer that is staring them in the face: the barrios. Alas, they remain wedded to a wholly inappropriate top-down modernist solution that has failed once already. Meanwhile, international brands such as Maggi have been much quicker to articulate these local behaviours, integrating their brand communication with the natural urban environments of the city. By embracing them, they get the opportunity to use it to their advantage. Maggi understood very well that ranchos are an undeniable part of Caracas city life.