Journeying through the vestiges of DDR urban development, Bram Esser traces a playful sketch of the shifting social climate of Berlin’s Lichtenberg district. Uncovering its past and present, while predicting its future, he reminds us that apparent urban failure can often conceal a thriving local community.

I. Herzbergstrasse 100. From the street, an innocuous office building, typical of the DDR. A monument signalling the frontier of Soviet bureaucracy, still standing strong while the society that produced it has long since crumbled. One era’s workplace, though, is another’s playground, and now the synchronized clack of clerk’s type-writers has been replaced with distinctive hum of Berlin’s underground.

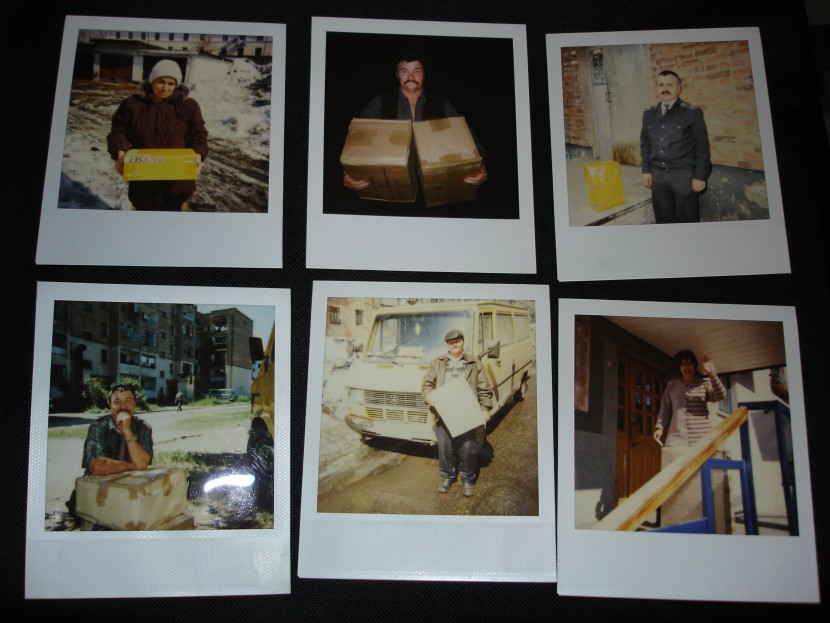

We enter through the basement, and a long dimly lit hallway greets us. We see no one, but hear the muffled sounds of drums, synthesizers and guitars. Following the music we enter a room and are met with a wall of distortion, hitting us with a cold beat which jumps from our heels to skulls. We move downwards and leave the office building through the back gate. We are in Lichtenberg, Berlin. The city’s historic attic space. A place where things are kept out of sight and expected to gather dust. Scrap-yards, overgrown plots and disused factories litter the horizon, broken up by high-rise apartments used to house mass influxes of immigrants. This is a land of pre-fabrication, with 150,000 plattenbau erected from 1976-1989 on once fertile farmland. Homes for settlers arriving from Russia, relocating to almost carbon copies of their previous USSR dwellings. Being from German descent, these immigrants were granted citizenship and quickly acclimated to their environment, creating a postal service to send care-packages to close-ones back in the USSR. A system that is still operational today, with packages collected in small shops attached to the plinths of apartment buildings.

Walking down Herzberstrasse we pass an Autohaus Europa. Pristine vehicles await prospective buyers. Between the plot and a two-storey apartment block we notice a small but deep stretch of land leading to an old railway track. A clothing line hangs between a fence and a sign forbidding trespassing. Passing under the trousers and shirts we follow the train lines into a thicket of trees and bushes, and survey the landscape which emerges from beyond the undergrowth.

II. ‘When my clients have collected enough fridges, car parts or televisions they order a shipping container with me and we send it to Africa.’ The owner of a local shipping agency, Contruck, tells us. Anybody can drive up to his business and sell goods, as long as they match the company’s standards. As we discuss the intricacies of his business, behind us, a container is being filled with worn out tires. Junk to our eyes, but a necessity in some parts of Africa, where second-hand rubber is used to fill empty spaces in cars’ frames, combatting the effects of harsh roads on delicate machinery.

Leaving Contruck we walk past warehouses and garages furnished with flower-beds and cactuses; hallmarks of Vietnamese culture. During the eighties many Vietnamese worked for Elektrokohle, the sole producer of graphite under the DDR, but after the ‘Mauerfall’ the factory went bankrupt, leaving the area impoverished. In 2005 Dong Xuan centre opened, rejuvenating the district. Consisting of nine hangars, which contain three hundred shops, the centre inundated the area with thousands of jobs, whilst flooding the local market with Chinese made curios. Walking through Dong Xuan local merchants present their wares, making impromptu bargains on clothes, electronics, flowers and the occasional toilet seat adorned with dolphins. Leaving the complex a group of germanised Vietnamese youths smoke Marlboro cigarettes in the car park, and we make our way past a makeshift shed bordered by a plastic Christmas tree and empty water tanks. We step onto fallow ground, marking the edge of the Vietnamese part of town, to wonder aimlessly between the cliffs of the plattenbau.

III. Encompassing Hohenschönhausen, Marzahn, and Lichtenberg and reaching all the way to Alexanderplatz, the plattenbau of East Berlin were primarily constructed by the housing corporation Arbeiterwohnungsbaugenossenschaft Elektrokohle Lichtenberg (AWG EKL) . In Lichtenberg alone 35 thousand people live in these buildings, most of which were renovated in the nineties.

Conceptually the plattenbau were born in Denmark, but came to represent Soviet socio-economics, being mass produced behind the Iron Curtain, with their distinctive grey facades visible from the Siberian tundra to the Afghani steppes. The buildings cold outer shells purposely offered shelter, but not warmth, being designed with a communistic concern for puritanical living. Of course people weren’t so easily shaped by this socialistic mould, and the contrast between the building’s plain facades and their interior decorations was impressive, with residents filling their flats with personal effects and designs. Even the exteriors of the buildings weren’t immune to alterations, and it was common to see painted doorways and walls decorated with motifs depicting scenes of local importance.

Today these buildings are often associated with social problems, harbouring poverty and criminal elements behind their dense concrete walls. A fact emphasized in modern Lichtenberg, where gentrification is rapidly dividing neighbourhoods. Two blocks away from Herzbergstrasse, newly built family homes appear on the edge of an old cemetery, territorialized by high garden fences, anticipating an influx of new settlers: middle-income workers.