On the eve of March 26th, Demetra nudges me with a sad, sobbing tone, “sweetheart, Michael Sorkin died.” The news breaks my heart. My insides squeeze tight. I drift away for a few minutes, allowing that tear to find its way out. I text Deen; he must be devastated.

I would like to imagine Michael among us, with a nonchalant demeanor, a smile that’s almost a smirk, and gesturing hands weaving connections and making sense of the worlds that tie us indiscriminately. “No rest for the wicked,” he would tell me. There is no time to reminisce, only to act, ethically and courageously.

Starting from the busy streets of his beloved New York, Michael advocated for collective, neighbourly, and walkable cities, while also practising architecture and urban design in ways that embraced these same principles. Even so, his shrewd wit always recognized the fallacy that architecture can change society by itself. “Architecture is never non-political,” he told Aleksandra Wagner in a 2006 interview “it always reinforces a set of social relations, whether within the family or between the ruler and the ruled”.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Michael’s work totally shaped my early consciousness of urbanism and infrastructure. In the late 1990s, while studying architecture in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War, “the end of public space” from Variations on a Theme Park had become my political mantra. Michael’s edited volume on the American (sub)urban landscape does not lament a loss. Instead, it recognizes a change and describes a path forward to endure and persevere through desires for collectivity, proximity, and intimacy. A young version of myself was fascinated with such prowess to critique and look forward simultaneously. It was also during this time that many urbanists and activists advocated for a more vibrant public sphere and public space in the highly controversial reconstruction project of Beirut’s old center.

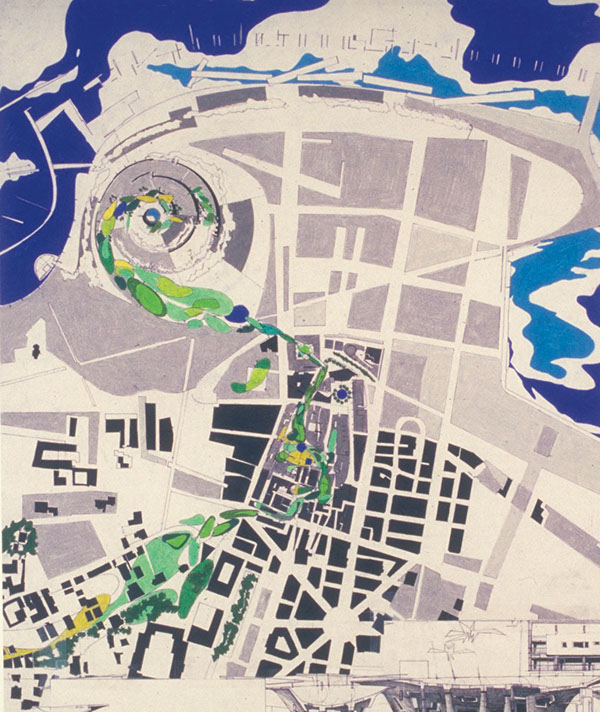

In their competition entry for redesigning the Beirut Souks, Michael Sorkin Studio proposed to reweave the divided city’s everyday life through a series of public spaces and urban programs that thread through its fabric, expunging the isolation of the center and breaking the new corporate grid of real estate planning. Alas, another architect designed the souks. They now exist as one big mall, a version of what Michael described as a theme park: “the place that embodies it all, the ageographia, the surveillance and control, and the simulations without end.”

Later, in a second-hand copy of the Architectural Record from July 2002 that I bought from Bargain Books in Beirut (a mini miniature of NYC’s Strand Bookstore), I read Michael’s article about politics through infrastructure in Occupied Palestine and how a sewage network might be the only common thing between Palestinians and Israelis sometimes (if any). It was not easy to grapple with my self-discovery back then. I realized how a hegemonic, cultural ideology pervaded our domestic urban and architectural pedagogy of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Until we read Yiftachel, Yacobi, and Weizman in “American” graduate school, our understanding of space, planning, and design romanticized a bygone version of Palestine all the way down. There was politics, then design. Michael’s writing showed me the opposite.

I met Michael many times after that.

An inspirational force to me since my days as a student of architecture, I felt an overwhelming mix of joy and awe when I first met him. It was 2012, and my first visit to New York City. I was considering a return to school as my ten-year milestone post-practice mental check. Being the busy New Yorker that he was, Michael met me with his graduate students at The City College of New York. We talked about Beirut, Palestine, urban design, and moving to New York. He graciously accepted a copy of my book on Beirut’s park Horsh Al-Sanawbar, and in return, offered to continue our dialogue and collaborate. A little pleasure that felt the world to me.

During my collaboration with Visualizing Palestine in 2013, I shared with Michael the Uprooted photomontage – a negative re-presentation of NYC’s iconic park. Equivalent to 33 Central Parks, the landscape depicted shows how the Israeli Occupation has uprooted 800,000 olive trees cared for by Palestinians since 1967. Michael replies:

Hi Fadi, Great work! I may have mentioned that we’ve begun a new publication – UR – as monographic journal of urban research … Kindly think about doing one! Hope to see you soon and to hear your take on what’s going on in that part of the world.

Best, Michael

PS We’re having fun in urban design! Come see!

Three autumns later, I reconnected with Michael when I pursued graduate studies at The New School. In his Lower Manhattan studio, he took me on an office tour and introduced me to the lovely Terreform staff. He invited me to collaborate on the Open Gaza project, among a brilliant crew of academics and practitioners. There was no better opportunity than this to loop the fantastic work of Visualizing Palestine into this corpus. Michael’s Against the Wall and The Next Jerusalem were already inspirations. This is what Michael facilitated: vigorous networks, relevant projects, and instrumental platforms for alternative imaginaries of what the world could be. How could urbanists think about the future of Gaza and Occupied Palestine? What theoretical and practical tools do we need to do that? These are not unique questions to this project, but damn right, they are among a few of such kinds of collaborative efforts.

So many others were closer to Michael. So many others are more qualified to speak of how we lost an architect, urbanist, activist, author, and teacher with Michael’s passing. To me, we lost a forceful and inspirational presence for social justice, Palestine, and humanity.

I am not sure how hard Michael’s last days were as his body struggled with this grim-reaping virus. Still, I would like to imagine from the safety of my home-lockdown in Manchester, UK, that he looked the virus in the eye and smirked at it infinitely. My sincerest condolences to his family, the Terreform crew (Deen, Vyjayanthi, Maria Cecilia, Isaac), the Open Gaza crew, and all fellow inspired urbanists.

This is a celebration of life. Stay ablaze with us Michael Sorkin, for there is “no rest for the wicked.”

Share your memories of Michael on this page.