Urban exploration and ruin photography have gained enormous popularity in recent years. Naturally, Failed Architecture is interested in this trend, as well as in the increasing fascination with urban decay. In this vein, we talked to photographer Matthew Emmett, who runs Forgotten Heritage Photography, about the views and motivations of an urban explorer (although he prefers to call himself a heritage photographer).

Following the interview is a selection of photos Matthew kindly shared with us.

Can you explain why the places you photograph fascinate you?

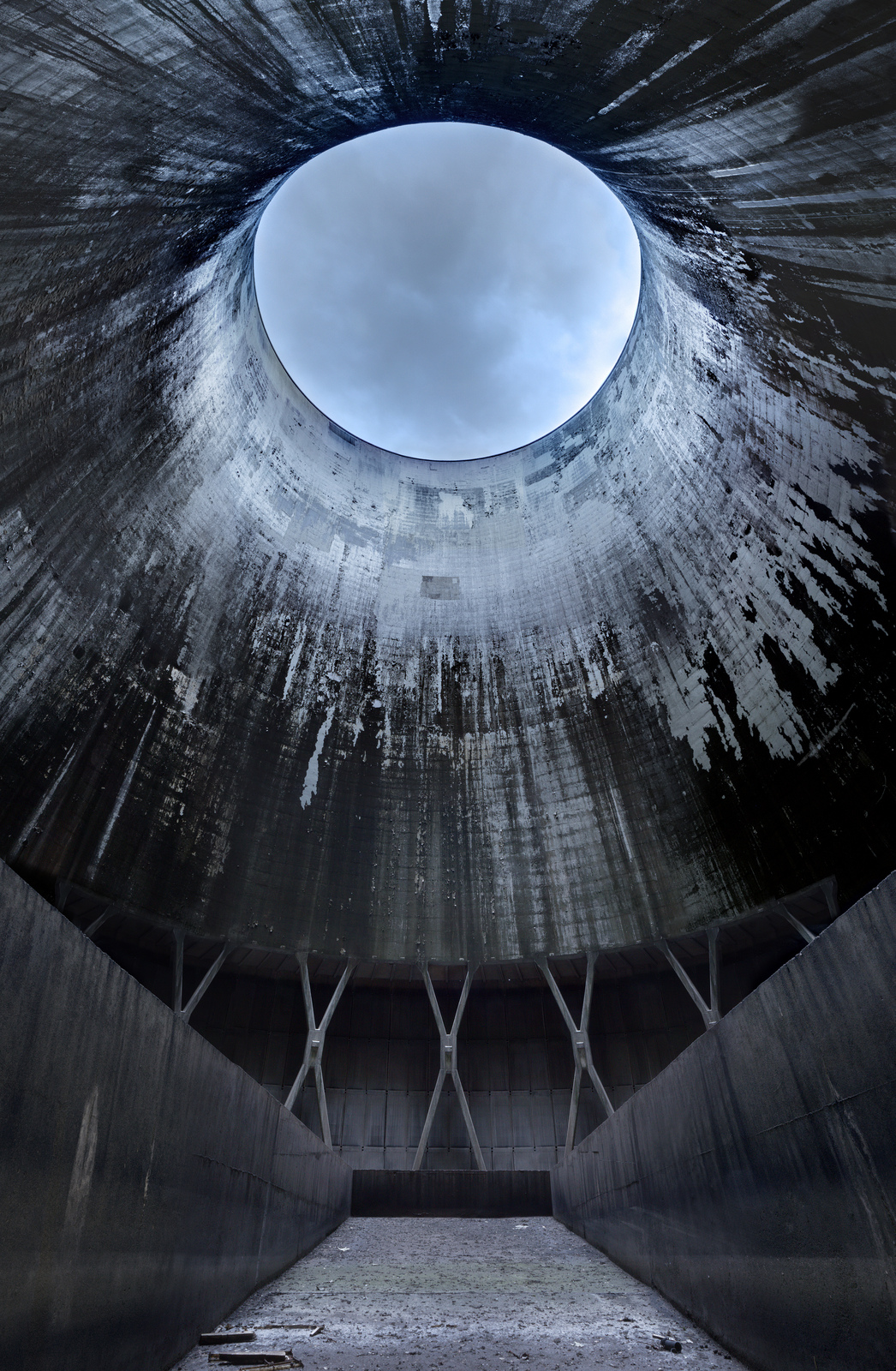

There is a thrill in exploring an environment that allows you to step into a previously unknown world and discover something first-hand, taking your time and noting the details as you go. Having a camera with me allows me to prolong that thrill long after the building is gone. It’s an often quoted cliché but there really is a strong sense of palpable history present in abandoned buildings, the items left behind like paperwork in a drawer or plaques or signs in an industrial plant, allow you a glimpse into the past. I consider experiencing these places to be a great privilege.

From the point of view of a photographer there is a total lack of distraction in the stillness of a derelict building; the sound and movement associated with people or workers has been removed, for me this makes them far more sensory than when they are occupied. Your mind can easily focus on what is around you and takes in so much more. The building’s voice is clear and a character and visual aesthetic emerges that was much harder to notice than if it was a busy, populated environment. Capturing this character and stillness comes across well in the photos and is something my target audience tell me they love about the work.

Do you conduct any research on the sites you visit?

I always read about a location before I visit, I try to have an idea of when it was in operation, what its purpose was, when it was abandoned and why. Depending on the impact the location then has on me I sometimes go much deeper and find out as much as I can. One such site was the National Gas Turbine Establishment (NGTE) in Fleet, UK. It was the leading site in the world from 1951 until 2000 for the design and testing of mostly military jet engines and naval gas turbine engines. The Concorde project had its own huge test cell built to fly its Olympus engines at over mach2 and at the cruising altitude of 57,000 feet. The site was magical and I quickly became completely obsessed with exploring it and discovering as much as I could find out about it. It brought me lots of new knowledge; like the detailed workings of a jet engine and the history of jet engine development.

It was demolished throughout 2013 with none of the plant, its unique structures or its technology being preserved or saved. To me this was criminal folly on the part of local government, considering the site was such an important part of the UK’s industrial heritage and aviation history, it is a sad indictment of the UK government’s commitment towards heritage. Now, a huge retail distribution depot will sit in its place (due in mid-2015).

Who would you like to reach with your photographic work and what do you think it communicates?

I am pleased when the work reaches and connects with any audience. I have followers on my photography page that love to simply look through the images, some then read further online and others use the work as a springboard for their own projects. Many people have commented that they plan to go out with a camera and discover what there is around their local area, which I think is fantastic. I also have work listed in several galleries and have recently had interest from a partner at one of the UK’s major architectural practices.

I hope the work communicates that there is impermanence in all things. All things rise and all things fall, human life and our creations. Life is a fleeting moment when compared against the passage of time on a cosmic scale; people should pull themselves away from the reality TV and games consoles and connect with their environment around them, something tangible and real.

People have different takes on ruins, abandoned buildings and other remnants of the past. Some want to break with the past, others call for preservation. What is your opinion?

I would prefer a location with a rich and important history to be preserved in some way. Funding for heritage projects is low down on the agenda for today’s cash strapped governments but also I think the wider public should take some responsibility for their lack of interest in the environment and heritage. I spoke to FAST (Farnborough Air Sciences Trust) about the preservation of some of the jet engine test cells at the NGTE. They said they had already looked into the possibility and it just wasn’t going to be cost effective, a relocated test cell would need to be made into a visitor attraction to make the cost of saving it viable and people on the whole were simply not interested in these kinds of things. The reality of the situation is a little depressing and I have no answers on how we move away from a culture obsessed with things like celebrity and reality TV.

There’s a discussion going on about the aestheticisation of decay, or ‘ruin porn’. Photographers are accused of beautifying distressing situations, without paying respect to the social or political reality of such places. What do you think about this, and how does your work relate to this debate?

I make no apologies for finding something positive, an uplifting or beautiful aspect to a situation that others may find distressing. Photographers didn’t cause the site to fail and fall into a derelict state and with my own work I don’t feel there’s a parallel with photographers who shoot among the ruins of a town like Detroit and the human tragedy unfolding there. The buildings I am interested in are uninhabited shells. I am interested purely in capturing the aesthetics, character and history of the building, showing the passage of time and the effects of nature on a structure that is no longer being maintained.

To use the example of the previously mentioned National Gas Turbine Establishment, the site closed because technology (computer simulations) had progressed to such an extent that the physical testing of engines became financially hard to justify. The government made no provision for preservation and it was passed for redevelopment. The photographers who entered the site have created an extensive and publicly accessible visual record for future generations and I can find nothing but positivity in that.

Why did you select these photos to be included in this article?

With a definite bias towards industrial and workplace locations, the selection of images I include with the article represent a good spread of the typical locations I photograph. More often I will try and capture the architectural ‘character’ of the structure as opposed to the human aspect of items left behind for example. I process the images to emphasise aspects within the scene but like to think I don’t go too far beyond the reality of what was. I hope the images convey my passion and respect for these structures and also inspire others to take an interest in their surrounding environment.