On Sunday, 18th October 2020, an estimated twenty-five thousand Chileans took to the streets of Santiago to commemorate the anniversary of last year’s social uprising, commonly referred to as el estallido (the ‘outburst’ or ‘explosion’). In a week’s time, the country would vote on a referendum to rewrite the country’s constitution, which was a holdover from the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. The atmosphere at the demonstration was hopeful but decidedly tense, and it remained peaceful until the afternoon when protesters started to clash with the carabineros (the Chilean police). By evening, news reports were saturated with footage of barricades, looted shops and, most strikingly, two churches on fire — San Francisco de Borja and la Parroquia de la Asunción — in front of which masked protesters danced in celebration.

Mainstream news outlets used the footage to vilify the “mob of lawless vandals”, and, for the most part, refused to engage with the protesters’ motivations. Meanwhile, authorities and media commentators rushed to condemn the church attacks, lamenting the loss of precious religious images and stained-glass windows, the hurt inflicted on religious congregations, and the damage to the city’s architectural legacy. But given the sorry state of so many heritage buildings in Santiago, it was hard to trust the sentiment beyond their words.

Such dissonance raises questions about what buildings are deemed worthy of preservation, and why. The churches, which had already been attacked during last year’s protests, have come to embody the current social order, an order that has its roots in Pinochet’s dictatorship, ideologically as well as structurally. The country’s political and economic establishment is not concerned with heritage preservation so much as with self-preservation.

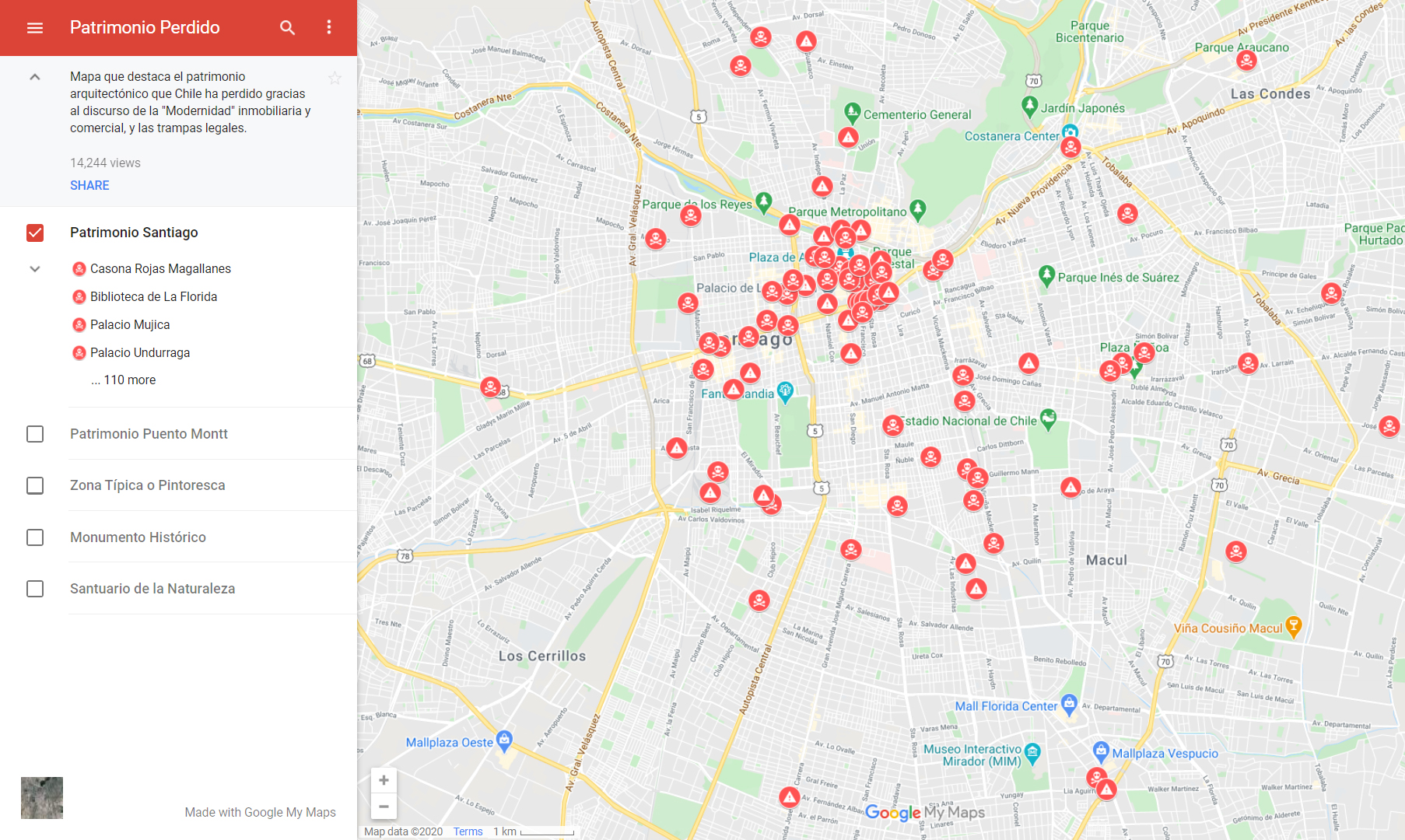

The patrimonia perdido map of Santiago, which highlights the architectural heritage that the city has lost at the hands of real estate and the discourse of “progress”.

A walk through the streets of Santiago Centro, the borough where the churches are located, is a bittersweet experience for architecture lovers: empty churches, old theatres, colonial palaces and modernist buildings are left to deteriorate until they are past the point of salvation, or until a fire or earthquake finishes them off. The outlook is even less promising for the humbler one- and two-storey houses once typical of this part of Santiago, occasionally featuring extravagant concrete bas-reliefs and ornamental columns meant to flaunt the modest wealth of their former owners. A lucky few endure as substandard accommodation for migrant families, who rent them by the room, or as car workshops and red-light bars. However even these are rapidly disappearing to make way for cheaply built, identikit high-rise apartment blocks.

Such disregard for this architectural heritage is a means for real estate developers to maximise profits through the dispossession of residents. The working class and lower-middle-class families who own and live in many of the old buildings have limited means to invest in their upkeep, and existing regulations offer little incentive to do so. As a result, they frequently have no option but to sell at a reduced price. A handful of real estate companies buy most of the plots, often leaving them empty for years, a practice encouraged by the abolition of anti-land-speculation laws during the dictatorship, which further lower the value of surrounding properties. Once a developer has purchased a number of contiguous plots, they take advantage of state subsidies to ‘redevelop’ the area. Building standards, already lax, are often circumvented, producing what Chileans call ‘vertical ghettos’: blocks of overpriced mini-apartments with inadequate facilities. These blocks, in turn, deprive the remaining low-rise buildings of light and privacy, putting additional pressure on their owners to sell.

Historians Cristián Palacios y César Leyton describe real estate developers as the spiritual heirs of the urban development policies formulated during the dictatorship by Miguel Kast (whose brother José Antonio and sons Pablo and Felipe have since held major political offices as MPs, senators and ministers). In the 1980s, a campaign for the ‘eradication of poverty’ resulted instead in the removal of the poor from the eastern and central areas of Santiago. With the help of the military, the authorities relocated at least 29,000 families from their informal settlements, to small ‘basic homes’ at the margins of the city, in semi-rural terrain with almost no amenities. The explicit goal of these policies was the ‘homogenisation’ of urban areas, with the wealthy in los barrios altos (notably, the municipalities of Vitacura, Las Condes and Lo Barnechea), the well-off middle classes in the centre (Providencia, Ñuñoa and, to a lesser extent, Santiago Centro), and everyone else in the western and southern boroughs.

Forty years later, displacing working-class and lower middle-class residents continues to be a winning strategy to increase capital gains and ensure these divisions persist. The referendum results attest to the enduring success of this class-based segregation: of the 346 municipalities that exist in Chile, only five voted to uphold Pinochet’s constitution. Among these: Vitacura, Las Condes and Lo Barnechea (the other two being Antarctica, which hosts a military base and registered a total of 31 votes, and Colchane, a town of 500 by the Bolivian border). A handful of families concentrated in these areas (140 individuals, according to a 2019 report by the Boston Consulting Group), hold 18% of the country’s wealth – a percentage that appears to have grown since the pandemic – and have dominated its politics for the past thirty years.

The estallido started at the beginning of October 2019, when high school students protested a 30 peso (less than four euro cents) increase in the Santiago metro fare by invading stations en masse, chanting, ‘Evadir, no pagar, otra forma de luchar!’ – ‘Evade, don’t pay, another way of fighting!’ – as they jumped over ticket barriers. All over the country, roads filled with barricades, and protesters torched several shops and metro stations. Within a fortnight, President Sebastián Piñera, evidently misreading the degree of public support for the protests, announced a state of emergency, putting the army on the streets for the first time since the dictatorship. “We are at war with a powerful enemy”, he declared, while attempting to draw a sharp distinction between legitimate, peaceful marches and the ‘criminal’ behaviours of angry mobs. He was met with more mass demonstrations and strikes. The protests channelled a wide range of social demands, such as the reform of the deeply despised pension system, a more equitable education system, the right to housing, the de-privatization of water, the abolition of the infamous child protection services (responsible for systematic physical and sexual abuse), and improvements to the overworked public health care system. As a frequently-used slogan explains, ‘no son 30 pesos, son 30 años’ – ‘it isn’t the 30 pesos, it’s 30 years’.

The protests reflected people’s exasperation with the neoliberal model imposed by the military dictatorship during the 1970s and 80s, and largely embraced by the governments that have ruled the country since the return to democracy in 1990. Steered by a group of US-trained economists nicknamed the ‘Chicago Boys’, Pinochet’s regime famously turned Chile into the world’s ‘neoliberal laboratory’. Following the ideas of Milton Friedman, the Chicago Boys advocated privatization, deregulation and cuts to public spending. Under their lead, Chile was the pioneer of what are now considered hallmarks of neoliberal governance, such as school vouchers, charter schools, pay-as-you-go health care and speculative pension funds. To this day, several Chicago Boys (such as Juan Andrés Fontaine and Joaquín Lavín) and their relatives (Sebastián Piñera and the various Kasts, for example) dominate the country’s political scene. More importantly, their ideas continue to be the basis of Chile’s economic and social policies.

‘Your normality is violent’ is another frequently used slogan, a response to the repeated calls for ‘a return to normality’ issued by media and state authorities. Indeed, discussions around what constitutes violence, and which forms of violence are legitimate, have accompanied the protests from the start. On the one hand, authorities decry the looting of shops, the vandalisation of statues, the destruction of pavements and traffic lights, and the disruption of traffic circulation. On the other, they shrug off the violence perpetrated by the military and the carabineros, who, in the past year, blinded more than 400 people using tear gas canisters and so-called rubber bullets, and arbitrarily detained, beaten and tortured many more. Over thirty people have died during the protests, at least six (and likely more) killed by the police or the military.

We generally think of violence as something explosive, instantaneous and sensational, but that is not necessarily the case. Sometimes, as environment scholar Rob Nixon puts it, violence is ‘slow’. It can be unspectacular and incremental, with effects that only become clear after years or decades. For many people living in Chile, ‘normal’ life is marked by the slow violence of chronic debt, rampant inequities, environmental contamination, frequent abuses by state institutions, and, since the start of the pandemic, food insecurity. Although deadly, these forms of state-sanctioned violence are easy to overlook for those who do not experience them firsthand. By contrast, footage of churches on fire and looted shops offers an instantaneous, hyper-real representation of spectacular violence that the government can leverage to generate fear.

Given that the San Francisco de Borja church has been the official church of the carabineros since the dictatorship, it is easy to see why some protesters did not feel inclined to appreciate its neo-gothic architecture, inspired by the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. It also surely didn’t help that the church is located in Calle Carabineros, just beside the fascist-style monument to carabineros who have died while on duty. Last year, protesters attacked the monument by throwing rocks and paint bombs. Now, despite the economic challenges brought by the pandemic, as well as the likelihood of further damage in future protests, the monument has been deemed worthy of restoration works to the value of 80 million pesos (just under 90,000 euros). Mario Rozas, then chief general of the carabineros, widely considered institutionally responsible for the police abuses of past months, told CNN that the attack on San Francisco de Borja made clear ‘who are the criminals, who are the vandals’. The minister for social development, Karla Rubilar, also expressed her support for the church institution on Twitter:

It is an enormous pain to see the burning church of the @carabdeChile, where people light candles to the martyrs who gave their life for us and destroying once more the shared heritage.

The other church that was damaged, the Parroquia de La Asunción, is also symbolically charged: its parish house was used by the political police and intelligence agency during the dictatorship, and allegedly also served as a torture centre. But rather than reminding viewers of this dark history, the TV news gave live updates about the kittens living on the church grounds, who were thankfully rescued by firefighters. That same night, 26-year-old Aníbal Villarroel was killed during clashes with the carabineros in Población La Victoria, one of the city’s working-class neighbourhoods. An investigation to establish the culprit is still ongoing, but several witnesses claim that it was a carabinero. What is certain is that Aníbal’s death received hardly any news coverage. No representatives from the government or the armed forces lamented the death, nor did they contact the family to express their condolences.

Neoliberal regimes tend to justify the need for free market economic policy and limited government spending through appeals to human dignity and individual freedom. Due to the enduring legacy of Pinochet’s violent ultra-nationalist military dictatorship, Chile’s current political establishment combines these appeals with a concern for the preservation of Chilean identity and traditional Catholic values. All of this they hold sacred, but only so long as it doesn’t clash with their more immediate financial interests. After all, these are the people who performatively display outrage at the burning of churches just as they insist that replacing historical houses with tower blocks is a rational, necessary step towards ‘progress’ and economic growth.