Anyone searching for a place to live in Amsterdam knows the city is dealing with a critical housing shortage. The waiting list for social housing is long, rental prices in the private sector continue to rise, and students have an increasingly difficult time finding an affordable room. Put simply, demand outstrips supply, which has created tension and imbalance in the housing market. At the same time, Amsterdam has continued to be an attractive destination for a wide range of tourists, who overcrowd the city center and pressure its capacity.

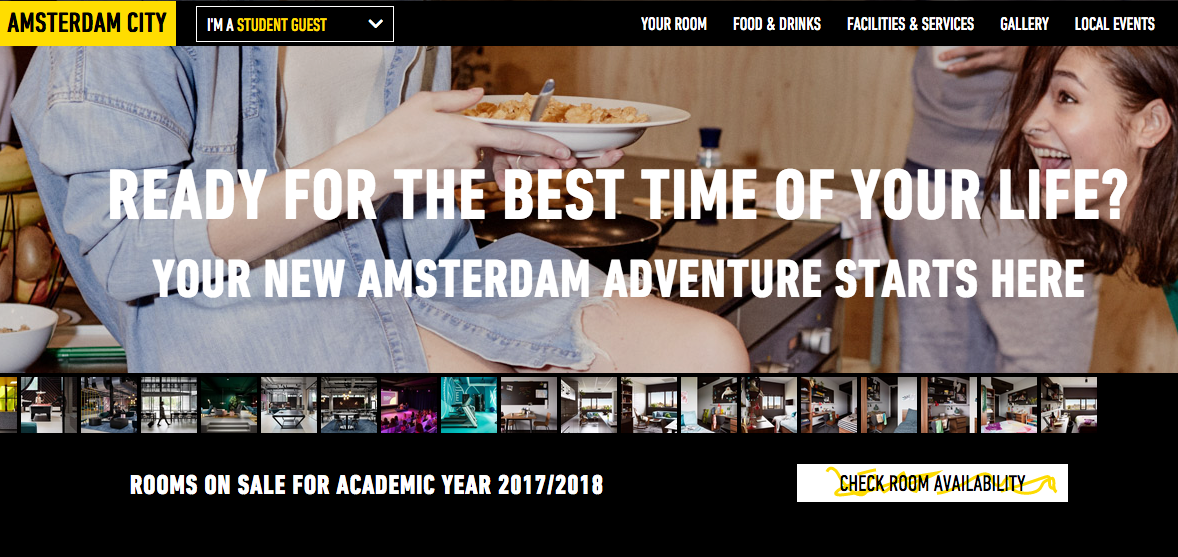

Two years ago, in response to the consequent lack of student housing and hotel accommodation, The Student Hotel opened its flagship location on the Wibautstraat, one of Amsterdam’s major traffic arteries, and a hotspot in the making. Introducing a new hybrid design concept that combines student residences, hotel accommodation and luxury collective living, The Student Hotel is a pioneer in the housing market.

Pursuing this innovative vision, the originally Dutch company creates student housing all across Europe. What started in Rotterdam in 2012 is now rapidly growing, with two locations in Paris and Barcelona and future hotels planned in over seven countries. The locations in the Netherlands are all hybrid models, housing both students and hotel guests.

The critical housing shortage has caused models of cohabitation to appear more and more often in the Netherlands, albeit with different intentions than those behind The Student Hotel. In Utrecht and Amsterdam for example, there are collaborative housing projects focused on housing students and refugees under the same roof, and in Deventer, students get the opportunity to live for free in a nursing home in exchange for thirty hours helping with the care of its residents. These two examples are not simply responding to accommodation needs, they also encourage the support of the more vulnerable groups in society. In contrast, The Student Hotel does little to support the creation of an open, inclusive and diverse city.

The company portrays itself as a community, a place that brings people together and where everybody is on the same page. However, The Student Hotel allows students to stay only for a maximum of ten months, which creates a community with a very short life cycle.

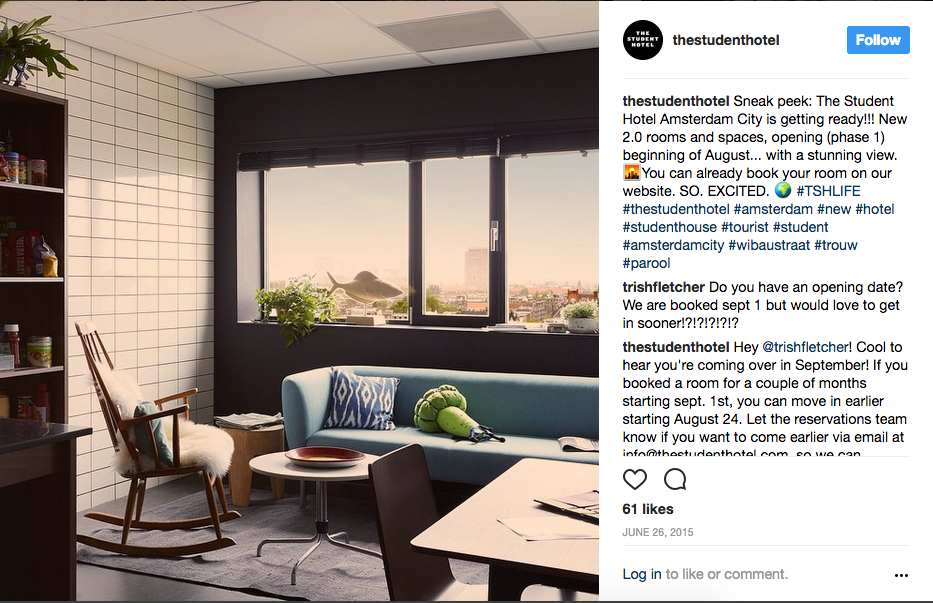

The hotel’s short lived communities are usually housed in converted buildings, where different design strategies are pursued. The company claims to forgo corporate identity and says every hotel is unique, complementing local traditions instead. However, all the hotels do have a similar current in their design pushing what the company sees as hip, trendy and cheeky.

A first glance at the Wibautstraat location does not suggest the presence of a trendy hotel. It is only when you approach the complex by foot, that you encounter a completely refurbished public space and a beaming new entrance, resulting in an interesting urban constellation, full of contrasts between the old and the new.

The complex consists of the thirteen-story ‘Parool tower’, former office of Amsterdam newspaper Het Parool, and the lower-story longitudinal ‘Trouw building’, former office of national newspaper Trouw and a popular nightclub before making way for The Student Hotel. Governmental regulations stated that the original architecture and materials of these late 1960s and early 1970s office buildings should be kept intact, so the company could not get rid of the sober exterior of the buildings.

Nevertheless, The Student Hotel still managed to extend the former newspaper headquarters by adding two new stories on top of the former Trouw offices. With their brown color and coarse structure, these stories seem slightly out of place on the grey, sleek concrete of the rest of the building, looking more like a temporary solution than a permanent addition.

Another major mismatch exists between the new entrance and the two existing buildings. In order to unite the two buildings, spatially and functionally, a large lobby was created with an entrance designed to give the sense of walking into a young and modern workspace instead of an outdated office block. This entrance does not open out directly to the Wibautstraat, nor is it in line with the other buildings. Instead you must walk away from the noisy traffic artery, across a square flanked by obnoxious bright yellow lampposts, over to the low black entrance that announces, again in obnoxious yellow, the presence of The Student Hotel.

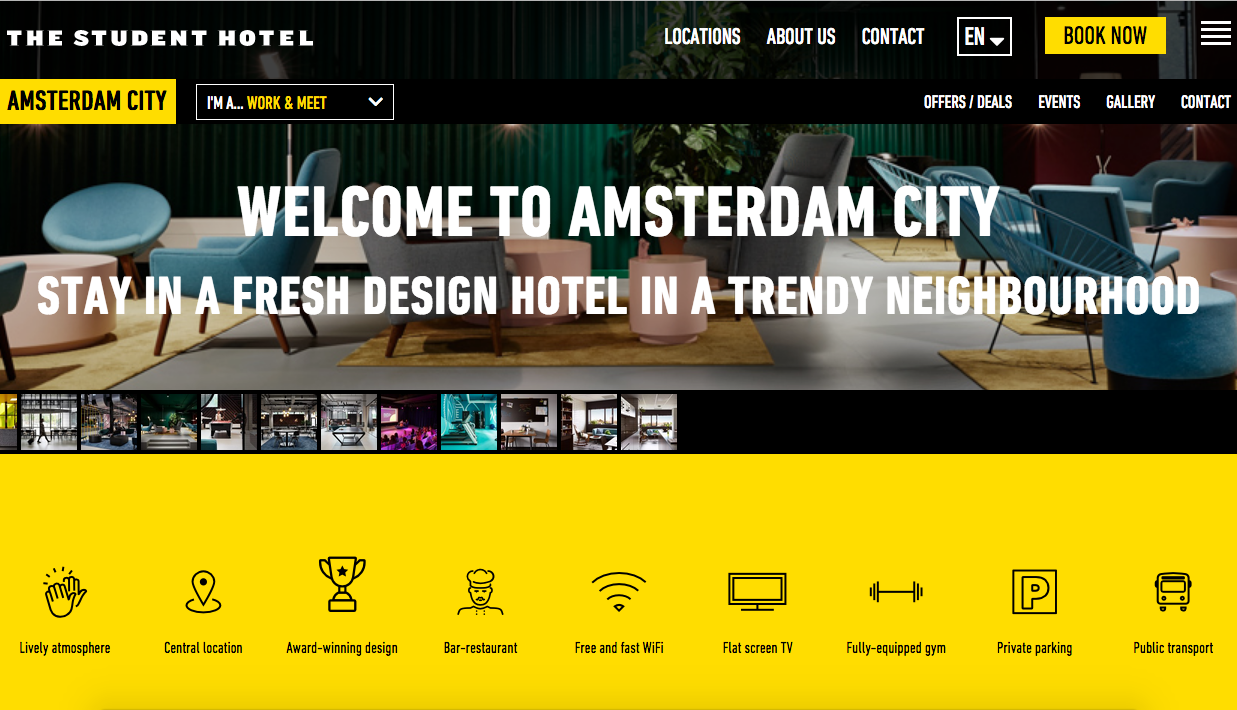

Upon entering the location, you immediately encounter a cacophony of styles and designs, something that is becoming a recurring characteristic of trendy hotspots. The Student Hotel’s attempt to be young and trendy is painfully obvious here. The lobby consists of many seating arrangements in all sorts of designs and colors, topped off with a bright yellow reception desk. To the left of the reception area we can find the student residences in the Parool tower, to its right are the hotel suites, the so-called play area, the food and beverages section, the laundry room and bicycle shed.

Apart from providing student housing and tourist accommodation, The Student Hotel also aims to be a workspace, with ‘flex’ areas where everyone can work, including a large auditorium as well as smaller meeting spaces. The common areas all have this eclectic combination of designs, reminiscent of the showrooms of a furniture retailer or vintage design store. This artificial atmosphere is a flaw recurring throughout these common facilities. Despite the goal of making people feel at home by providing the familiarity of vintage and eclectic designs, there is no domestic warmth to be found here.

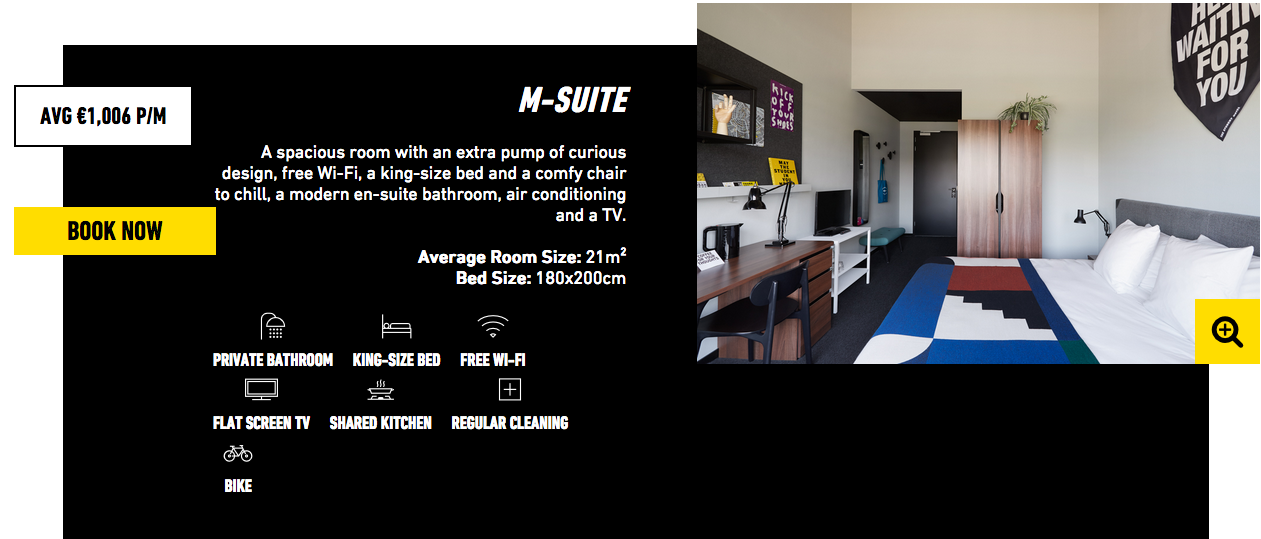

The brightness and diversity of the common areas is as extreme as the blandness of the hallways, individual rooms and communal kitchens in the Parool tower. This stark contrast between public and semi-private is striking and the dreariness of the rooms feels as a relief after the flashy and obnoxious environment of the public spaces downstairs. These basic looking but well equipped student rooms cost approximately between 875 and 1032 euros a month, with sizes varying between 14 and 19 square meters. Each comes with a small private bathroom, whereas the kitchens are communal. These prices are far above average for student accommodation – one wonders how students can afford to rent a room for 875 euros, let alone a so-called ‘panorama executive’ suite with an extraordinary skyline view for over 1000 euros.

The Student Hotel exemplifies the approach of contemporary luxury communal living arrangements for ‘millennials’, legitimizing high prices by adding a large amount of superfluous facilities, such as the free to use ‘play area’ with ping pong tables, large television screens and game consoles, a small gym and various food and beverages sections with an obligation to consume.

With all its shared facilities, organized parties and the overall idea of having everything under one roof, The Student Hotel presents itself as ‘the complete connected community’. But perhaps it is more accurate to say it is a modern and incognito gated community. Although there are no physical gates or barriers preventing unwanted guests from entering the community and though the lobby of the hotel is in fact accessible to all, The Student Hotel is only accessible to few. While the barriers between work, play and life might be breaking down for those inside, new barriers have been established by its exclusive luxury features, thereby enclosing the community from those outside.

For the wandering tourist, a stay in this hotel does not seem to be the worst of all options; the rooms are clean and comfortable, the location is excellent and the common areas create the vibrant atmosphere of a youth hostel but with more comfort and space. The price to quality ratio is also fair given the current state of competition in the tourist accommodation business. When it comes to the student housing aspect though, one wonders: why would anyone want to live there unless absolutely necessary?

With prices starting at 875 euros a month for a single room, the concept of The Student Hotel is inclusive in the literal sense. Dutch students, for example, can currently take a maximum monthly loan of 1033 euro. Above all, we should not only question if this is what students need, but also if this is what the city needs. A city should be open and inclusive to every section of society, whereas businesses such as The Student Hotel foster segregation.

Their concept creates a group of people that will indeed form a community, but a very exclusive one. It is not just the unaffordability that keeps people out, the extra luxury commodities along with the insular social circles will keep members separated from those without the right means. The residents and visitors of The Student Hotel might be connected to those within their bubble, but not to the outside world.

If The Student Hotel truly aims to revitalize neighborhoods and to create diverse communities, why provide even more for these wealthy segments of society when they have already so much to choose from? Why not provide cheaper rooms with less luxury commodities and strive for a truly open arrangement? The answer to the last question is obvious: it is not as profitable.

According to The Student Hotel’s CEO Charlie MacGregor, renting out small rooms for a small price does not fit into a profitable business plan. By licensing the company as a hotel, he found a loophole in the property valuation system on which the maximum rent is determined. In the case of a hotel, you can make the room any size you want, and ask any possible price for it. Furthermore, you are not locked into a contract and can evict people whenever you see fit.

The continued exploitation by companies such as the Student Hotel makes Amsterdam increasingly segregated. The neglect and carelessness of the municipality and national government has allowed this critical situation on local housing markets to proliferate. There is no time for idleness – immediate intervention is necessary.