The former Yugoslavia has always been a breeding ground for conflict. Due to its geographical location between Western and Eastern Europe, many powers, both before and after the First World War, had an interest in conquering this region, resulting in a mix of different cultures, religions, and heritage. After the Second World War ended, Yugoslavia was in ruins. Josip Broz, better know as Tito, became the leader of the country. To deal with the nationalist tendencies within the region, he introduced a strict socialist regime, which emphasised the similarities and mutual dependency of the different ethnic groups of the six republics within the region. Especially after the Second World War, Yugoslavia became a laboratory for making different ethnicities and religions work within the same nation via education, media, theatre, film and architecture.

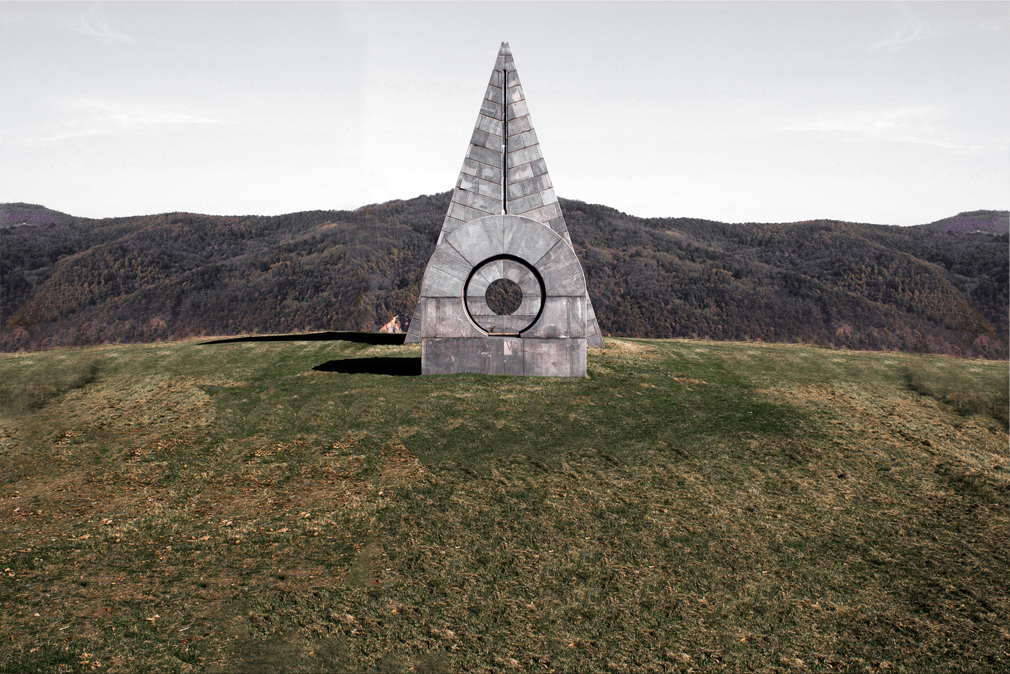

Architecture has played a big role at many different points in the history of this area, particularly during the decades after the Second World War and around the Yugoslav War. Symbolism through monuments or structures had great importance during these events, not only by strategically placing them in public space but also by destroying or avoiding them. From 1960 until 1980, Tito commissioned more than 100 monuments commemorating the victims of fascism. Remarkably, these monuments did not recall the Second World War, but looked towards a future of freedom, equality, independence, progress and a better life for everyone – a future that could only exist thanks to the fact that others had given their life. In order for the monument to appeal to all different inhabitants (regardless of their nationality or religion), a new form of language had to be invented. Consequently, these monuments do not contain the symbols of ideologies, war heroes, or religions. Instead , they are abstract forms that refer to the modern future. In a country with many different cultures, ethnicities, identities and truths, these monuments–regardless of their location–belonged to every Yugoslavian. These monuments parted with a history in which there was always tension and a place where borders were constantly shifting.

The monuments, along with their often natural surroundings, were designed to become public spaces where people could hike or simply lounge. Yearly student excursions to these monuments were organised, where they learned about the history and the origin of Yugoslavia. More important than history, however, students were taught that their comfortable life in Yugoslavia – in which everything was good, equal and developing – was only possible thanks to the battle that the victims of fascism had fought in that very area. This derived from the conviction that unity can only be created when people have a common future.

The monuments are, for the most part, located in areas where the fiercest battles against fascism took place. Each monument – both those in the city and those in more pastoral landscapes – is located at a completely unique place within their context. The visitor has to put effort into getting to the monument (they have to, for instance, climb a long path upwards) and once at the monument, the visitor has the experience of being disconnected from the world. However, all the monuments can be experienced in different ways, as each monument employed symbols that had a connection to the specific location and the events that happened at the spot located. Every visitor experiences each monument uniquely based on his or her connection with the location or with historical events.

Each battle – and the one against fascism of the Second World War is no exception – has winners and losers. The winners, along with the people who chose the side of Tito’s Partisans, saw the monuments as places of victory, while the losers and fascist occupiers regarded them as places of humiliation and surrender. Despite these differences, the prevalent way of thinking was that the Partisans had fought a great battle and had done fantastic things during World War II. This was glorified at schools, or in the many films that were made about the Second World War.

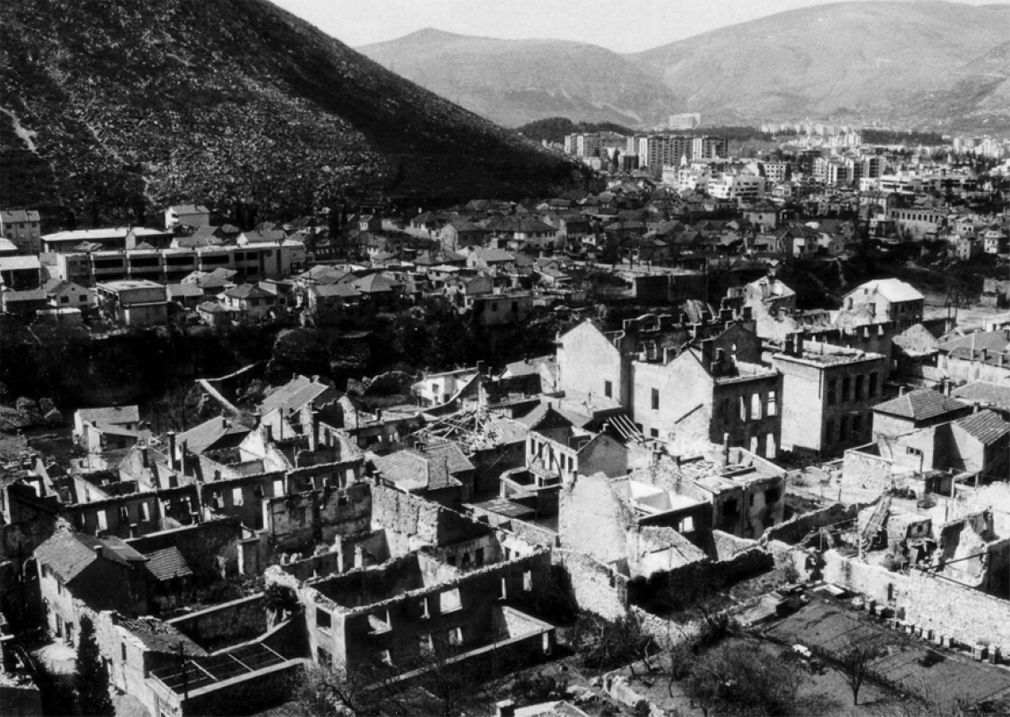

Due to each of the monuments’ location, use of material, construction and sheer size, the monuments could not be demolished during the Yugoslavian civil war. However, because of this war, their meaning has shifted; the majority of them have been either damaged or left to nature. Each monument is a tombstone that reminds visitors of the land that used to be called Yugoslavia. While not all, some of them are located in cities that were mostly demolished during the civil war and are now ethnically divided, such as Mostar (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and Vukovar (Croatia).

Architect and urban planner Bogdan Bogdanović (1922 – 2010), originally from Belgrade, was one of the architects who designed these monuments. During the same period that he built and designed these monuments (1960 – 1980), he wrote 18 books and over 500 articles mostly on subjects like ‘the death of the city’, ‘the city in history’, ‘critique of the modern city’ and ‘utopias’. Besides that, he taught at the architecture faculty of the University of Belgrade, served as mayor of Belgrade from 1982 until 1986, and during the 1990s fought against the ‘ritual killing’ of cities. He spent his whole life studying the rise and demise of cities, visiting many of them at the point that they were in ruins (some examples are Gdansk, Lviv, Arnhem, Rotterdam, Novgorod, Lubeck, Rouen). Bogdanović regarded cities as people, believing that each city had its own soul for which legibility and historical layering is important. He believed that when a city ceased to be legible, it was questionably no longer a real city, leading to its eventual actual demise.

Like the other monuments, the ones designed by Bogdanović lack any symbolism of ideology, war heroes or religion; however, most do employ a language that references old mythology, the Renaissance and the Baroque periods. Consequently, many of his monuments do not refer to a modern future, as is the case with most of the other monuments discussed. Because of their archaic form language, they look like they have been standing forever and remain for eternity. Bogdanović always tried to express one of the elements – fire, water, earth and air – with his monuments. He has made work that was site-specific and employed spatial qualities and materials of the direct environment. One example is Partisan Necropolis in Mostar, which is dedicated to earth and stone. In the rocky Mediterranean city which the monument is set, there is a tradition of carving relief out of tombstones, pebble-paved roads and legacy of building on top of rocks. Following these, Bogdanović designed a cemetery commemorating 810 Partisans from Mostar. He described the monument as an ‘acro-necropolis’ and as a microcosmos of the city of Mostar – a city of the dead mirroring the city of the living. The cemetery has the same pebbles, alleys and gates that are so characteristic for Mostar.

Visiting Bogdanović’ monuments was a special experience. This was because of the mystical nature of the locations, locations that were precisely chosen. Oftentimes the monuments suddenly emerged in the landscape, with very little warning that a monument was nearby. The paths to the monuments were tortuous and the décor was constantly changing. The paths would often at first lead away from the monument, and towards the end suddenly take a sharp turn towards them. Once on site, the visitor was overcome with the feeling that the location was both new and surrealistic, yet a very ancient, location – an environment where one lost contact with the everyday world.

Both Partisan Necropolis and Dudik Memorial Park in Vukovar (Croatia), which was also designed by Bogdanović, are now located in cities that were, for the most part, destroyed during the civil war of the 1990s. The ritual killing of cities, something that Bogdanović had feared, happened in these locations. Once again architecture was used at a turning point in history. Buildings and public spaces that served important cultural functions with which inhabitants could identify were strategically bombed. The legibility of their history and identity disappeared. By demolishing important symbolic architecture (like schools, libraries and museums) a big part of the culture was also destroyed. The cities that housed different ethnicities were hit the hardest.

Currently these cities, once repositories of memories, have become dishonest and opaque as politicians try to keep the different ethnic groups divided via architecture. As the legibility of the history and the identities have disappeared, communication between inhabitants and the city has ceased to exist. History, symbols and memories are currently being erased in these cities by adding unfitting symbols or by removing meaningful symbols in public spaces. This has resulted in an abundance of fragmented, imaginary, self-proclaimed and self-imposed memories. In the case of Mostar, inappropriate symbols and monuments are added to the public space. Street names have been altered, and ethnically and politically biased institutes get prominent places in the city. What used to be one of the most successful public places of the city – café Rondo and the adjacent House of Culture – now has a monument dedicated to the Croatian Defenders (in the form of a cross) placed upon the café, and the House of Culture has been transformed into a House of Croats. Everything that does not fit in with the new ‘history’, such as the Partisan Necropolis, has been neglected. Dudik Memorial park in Vukovar was also heavily damaged during the war as well. While a large part of the destroyed city is currently getting rebuilt, the monument remains in ruins.

Can these monuments acquire a new meaning within this new context, and if yes, what would it entail?

The monuments were a reflection of their time. At a single location, a monument can simultaneously tell something about a country, an area, a city, a battle and a history. It is as much a reflection on society as it is a utopian message about the future. The monuments have the ability to address multiple nations, ethnicities and religions (from over the whole world), which normally would be irreconcilable. These monuments were meant to be ‘isolated’ places from which people could acquire a positive stance towards the future and at the same time would commemorate those who have died fighting fascism. Nowadays the monuments are places that remember the time that the land where the monuments are built on was called Yugoslavia but also commemorate the demise of that country. They represent both utopia (for many, former Yugoslavia is a utopia: a time when everything was better) and dystopia (the civil war of the 1990s and the collapse of Yugoslavia).

What is so extraordinary about these monuments is that they never represent the present, but always the past, the future or – as is the case with Bogdan Bogdanović – eternity. Currently, in the present, the demolished cities that were described earlier employ architecture as a continuation of the battle instead of rebuilding a city after the battle. Nowadays the monuments that are located within these destroyed cities are one of the few places that offer legibility and reflection (societal and historical). This makes them extraordinary places because destroyed cities are places where everything is burdened with tensions, and where truths and meanings are imposed. These cities do not have any counter-places. No places where culture and society are both represented, contested and turned upside down. This makes that the monuments can still fulfil an important role in the destroyed cities. A role that is perhaps even more important than the one they used to have in the past.