Camsoda Press Release, July 29, 2020 – CamSoda unveiled its plan to deploy pop up studios housing individually sanitized pods for models to broadcast from during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pods – the “new normal” for adult webcamming – will help meet demand for increased camming by models all over the world. They will also aid in ensuring the health of webcam models who have to broadcast away from their residence because of spouses, family, roommates and other houseguests who are now working from home. The studios will be within large, centralized buildings to allow for proper social distancing. CamSoda has tested the studios in Colombia and is looking to expand into the United States. The first US based studios are slated to open in Los Angeles, New York, and Miami.

Porn consumption increased considerably after the pandemic, helped along by fewer outdoor distractions and more solo screentime. Pornhub, for instance, registered a 24,4% peak increase on March 25th, after it offered free access to its premium features as a means “to encourage people to stay indoors and distance themselves socially”. At the same time, live streaming sex webcams saw a resurgence, thanks to their offer of an alternative source of income for many people who have faced fewer working opportunities due to the economic and physical consequences of COVID-19. With elevated porn consumption and newly sanitised COVID-proof environments, it now appears that sex camming is evolving into an industrialised, almost factory-like controlled workplace.

Promising a more democratic and unmediated means of pursuing online sex work, adult live video cam platforms seemingly give cammers more control over how their bodies are displayed, how many hours they want to work, and under what conditions. But despite the personal freedom they afford, the virtual nature of these workspaces also contributes to the decentralization of sex camming as a “collection point for labour-power” to use a phrase from Red Schulte in their recent article for The Funambulist, where they describe “The brothel, the bawdy house, the saloon, the massage parlour, the sex theater, the peep show [as] physical spaces that are ultimately influenced by the labor of those who maintain them”.

To be a sex cam performer, now more commonly known as a “cammer”, apparently all that’s required is to register on one of the many platforms that now exist, agreeing to their terms and conditions, giving them a share of any earnings, and complying with each page’s privacy statements. This point of entry already represents a significant difference from the porn industry where porn stars have frequently reported having had to sit in a room full of producers and sign a contract under psychological pressure.

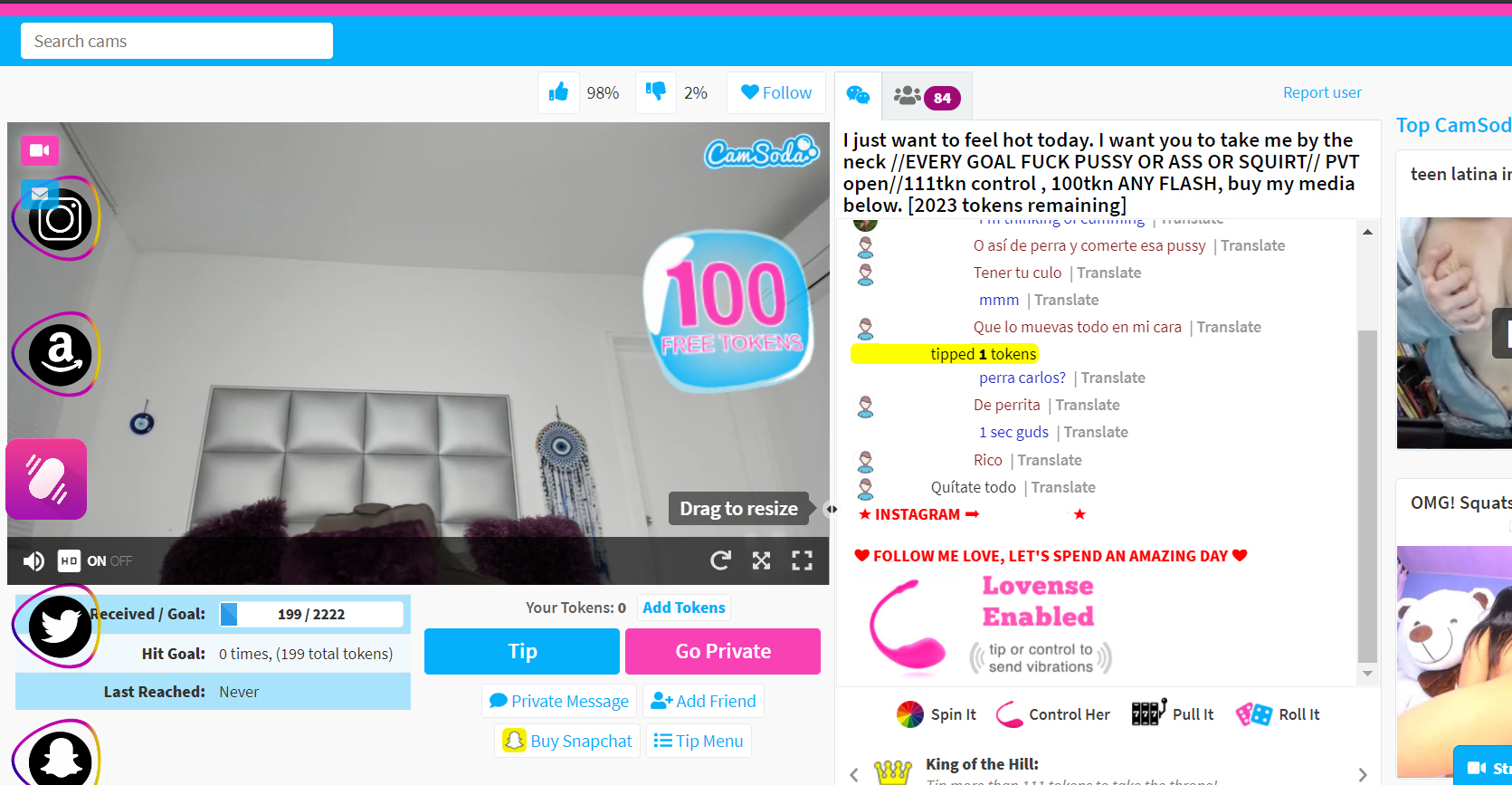

By contrast, in any given sex cam website terms and conditions, a lot of effort is spent trying to deny the fact that sex workers are even using their platforms to earn their money. Most of them describe themselves as a social networking platform. They also include a statement where they deny any approximation to sex work while at the same time incorporating several clauses about sexual conduct and content, and featuring ads from sex work-related services. On the popular sex camming platform CamSoda, the financial exchange is obscured through goals, tokens and commands. A cammer might, for example, write to viewers “I just want to feel hot today”. The goal is reached when viewers pay enough tokens to match the value established by the model. “Tokens” is sex camming-speak for cash. They are often spent on giving video game-like commands to the cammers: spin it, control him/her, pull it and roll it. Except for ‘control him/her’, which works via the use of electronic sex toys that can be paired with a computer, all the other commands direct a slot machine, which will spin a wheel of available commands, and stop at a random one.

Meanwhile, on Only Fans, a website that has seen a particular surge in popularity since the pandemic, sexual interactions take place in an equally indirect way. Also describing themselves as social media, but only for people above 18, Only Fans’ current success seems to come from its emphasis on being an environment that favours self-expression (much like Facebook or Instagram really). Despite this, it is popularly known as an adult content website, which also operates on posts of erotic photos and videos, and not only live webcams. It is not exclusive to sex workers and counts several celebrities among its content creators, including Cardi B. Only Fans’ terms and conditions page states that they do not own user content, are not represented by the users’ views, and are not responsible for any transaction or interaction between users, except if they act as agents to receive payments. Should the latter be the case, which is the only way to access any content, their commission fee is 20% in each transaction.

Porn and sex camming do still overlap in their visual strategy. Both focus on the genitalia and breasts, in close-up, almost suggesting that emphasis on the movement and interaction with the performer’s sexual organs is the most immediate way of catering to the viewer’s pleasure. However, there is a crucial difference in how the engagement with the audience happens in both. While porn is mostly an acted narrative, perhaps except for amateur porn, a sex cam is live. The live stream is a shared experience between cammers and viewers.

Sex camming also technically has no directors, editors or producers. Instead, the directors are the cammers, who orchestrate the images and actions. The viewers take on a more editorial, scriptwriting position, issuing commands and, guiding the sequences, choosing actions via the controls. And meanwhile, the websites take on the role of producers. Social and power hierarchies are different. The employer (the website) is decentralised and is no longer represented by the figure of a person, a boss. More emphasis is given to the employee (performer) as the main organiser of their schedule and content.

While online socialisation has long ceased to be an unfamiliar experience to most people, our bodies have acquired an increasingly digital quality as a consequence of the coronavirus pandemic. Even so, the impact that the combination of technology and architectural space have on bodies during a global pandemic is by no means novel. In his essay “The Architecture of Sex –Three case-studies beyond the panopticon”, Paul B. Preciado illustrates how architecture and design have dealt with sexuality and technology in the context of previous global crises. From the design of a brothel in 1780 as a response to the Syphilis outbreak, to the project of the American suburbs, and the design of the contraceptive pill receptacle, architecture has presented itself as a mass medium through which the state administers racial segregation, controls sexuality, particularly that of women and “homosexuals”, and thereby produces immunity for white heterosexual men. In the specific example of the North American suburbs, Preciado writes “The suburban home was a decentralized factory for the production of new performative models of gender, race and sexuality.”

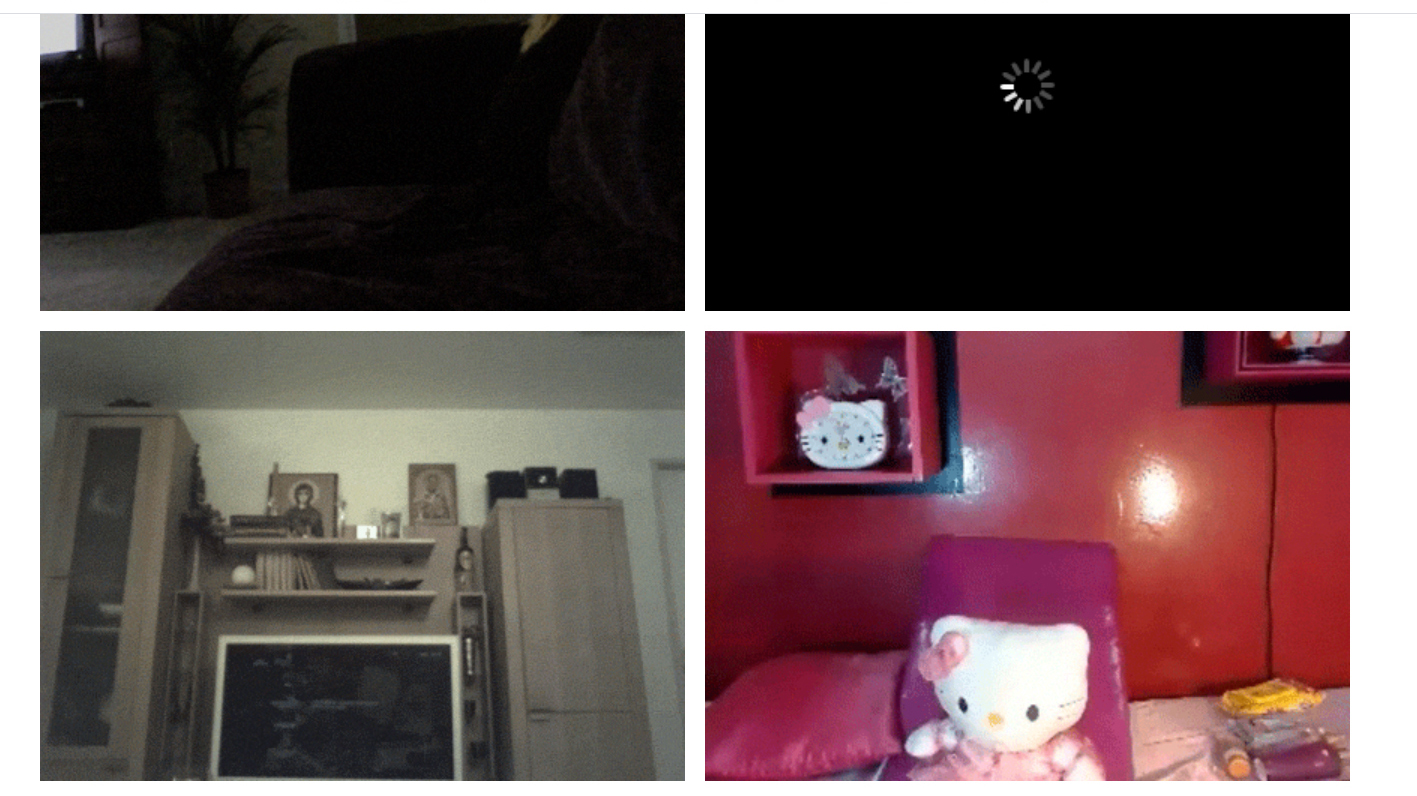

The home as a factory is also evident in sex camming. Unlike most spaces and content designed for sex, where causing wonder through extra-ordinary architecture is often the architectural goal, homeliness is the pre-condition of sex cam scenarios. This was made explicit through the project brbxoxo.com, where artists Addie Wagenknecht and Pablo Garcia collected videos of sex cams only when the performers were absent. As soon as someone appeared in the shot, the video switched to another empty room. Stripped of the action, the rooms make clear that the connection between sexuality and space is also manifest in the territory of the trivial and the everyday. Some of the rooms depicted contained dolls, toys, images of saints, posters of films or plants. Except for an occasional dildo laying around, there’s nothing particularly out of the ordinary. If we did not know the context, it’s safe to say there’s nothing explicitly erotic about the rooms themselves.

This sort of de-eroticisation can be more clearly visualised thanks to the new strategies adopted by camming websites like CamSoda. Warehouses that have been emptied due to the COVID-19 outbreak are now being rented and equipped with corona-proof, condom-like, transparent pods that simulate sterile versions of the usual domestic environment seen in the traditional sex cam setup. Although Camsoda’s press release makes it seem like this is a decent gesture from the company —providing their clients with more stable working conditions— it also represents a worrying opportunity for them to re-establish the employee/employer disciplinary dynamic in physical space. And while these factories do not house all of the cammers registered on their website, the terms and conditions of the websites take away another good chunk of the control cammers had when they were working inside their own homes. Unlike other spaces destined for sex work, like brothels, these factories have no interaction with a physical client base, nor with the city at large. As a result, it’s harder to see these spaces becoming collection points of labour power (to use Schulte’s phrase).

This industrialisation of sexuality in the domestic context, brings us to another argument made by Preciado in “Feminism is not a Humanism”, an essay featured in his recent book “An Apartment on Uranus”: “The first machines in the industrial revolution were not steam engines, printing presses or guillotines…but slave labour on the plantation, sexual and reproductive female workers, and animals. The first machines in the industrial revolution were living machines.” Now, with centuries passed since the industrial revolution, we see in the factory cammer a subtler and more intense spatial manifestation of the living machine, producing algorithmic sex surplus within the confines of industrialised intimacy, a diffuse system of governance masked by a glossy digital interface.