British press recently revealed that Junya Ishigami + Associates, architect of the 2019 London Serpentine Pavilion, uses unpaid interns within their office. Though it may come as no surprise to those working within the profession, it was news to everybody else: even renowned architects don’t pay their staff. Yet while there are exceptions to be found, the practice of employing unpaid interns is a defining element of a working culture where labour exploitation is rife.

Current surveys from the British Architects’ Journal (Working in Architecture, Student Survey, Race and Diversity Survey) paint a concerning picture of what it’s like to work in architecture. According to just a few of the findings, 24% of participants were victims of racism in the workplace, 1 in 7 women have experienced sexual discrimination and harassment, women are paid up to 24.5% less than men, and 40% of participants work over 10 hours overtime per week. These findings are further supported by a recent report which found that 23.7% of professionals had contractually agreed to waive their right – afforded to them by the Working Time Directive – to work no more than 48 hours a week. Any agreement to give up this right must be voluntary, and pressure or discrimination on the refusal of this is illegal. Nevertheless, the same survey also revealed that almost a quarter of the people who signed the clause had felt like they would not have gotten the job unless they opted out.

Faced with this level of acquiescence, the case for unionising the profession becomes compelling. As a regulator of working conditions and a protective body for workers, a trade union would force the industry to adapt to healthier working conditions; without these decisions being left to the leading staff and management who are themselves usually under pressure to attain expected productivity levels.

Trade unions are behind some of the most cherished aspects of contemporary work culture: the five-day working week, annual leave, minimum wage, and the abolition of child labour. Among many other standards we expect in today’s workplace, these are the product of the historic struggles of worker organisation, protest and demand. Countless sectors have benefitted from unionisation and collective bargaining with their employers. These benefits have concerned not only industry-specific working conditions, but also issues of public interest. For example, the British Medical Association has been lobbying for medical and public issues for nearly 200 years, whilst campaigning continuously for fair pay and conditions in the sector. Architecture needs to catch up.

The current professional body for architects in the U.K. is the Royal Institute of British Architects (the RIBA). The RIBA functions across many different levels: campaigning, promoting, exhibiting, awarding, publishing and offering a private venue for rent in its large central-London space. It also offers many client-facing services, such as client advisor roles, ceremonies and project competitions. However, it is not a trade union, as evidenced by the fact that it has made no commitment to reprimand or regulate employers who normalise poor working conditions to date.

At a debate in London last February, Lucy Carmichael, then Head of Professional Communities at the RIBA, stated that a trade union would be “an indictment on the professionalism of architectural practices”. Given the threat that a union could render the RIBA irrelevant, it’s unsurprising that she would be dismissive, but the claim that a union would jeopardize the architect’s professionalism is a dubious one.

As a professional category, architects might be completely alone in thinking that unionising would damage their professional image or status. Many other professional groups have recently taken industrial action against precarious contracts, falling-pay and working hours. Junior doctors fought the NHS in 2015, and in 2018 barristers took on the Crown Prosecution Service and higher education staff took strike action against their institutions, all while keeping their professionalism intact.

Workplaces more similar to architectural practices have recently gained a lot of ground in collectivising demand and reforming the way they work. One international group whose footsteps architects could follow is the U.S. ‘Tech Left’, groups of tech industry activists promoting labour representation and teaching their colleagues that “tech work is work, even though it doesn’t take place in a factory”. According to these groups, many tech workers are employed on temporary, unpaid or minimum wage contracts, they’re not paid for their overtime and they often work excessive hours (sound familiar?). This often occurs in start-up companies, where employers sometimes even fail to pay basic wages on time. Recent efforts from groups of workers such as Tech Workers Coalition (TWC) and Tech Solidarity have produced and staged numerous successful campaigns, pledges and protests – all geared towards exposing unethical industry practices and exploitative labour conditions among all members of staff (including non-qualified workers), while also establishing a digital support network for workers.

These groups represent a new generation of white-collar activists who refuse to be complicit in unethical corporate practices. For example, in 2017 members of the Tech Left took to the street outside Palantir Technologies headquarters, responding to the revelation that the company would be producing intelligence technology that could be used by immigration services for the purposes of deporting people.

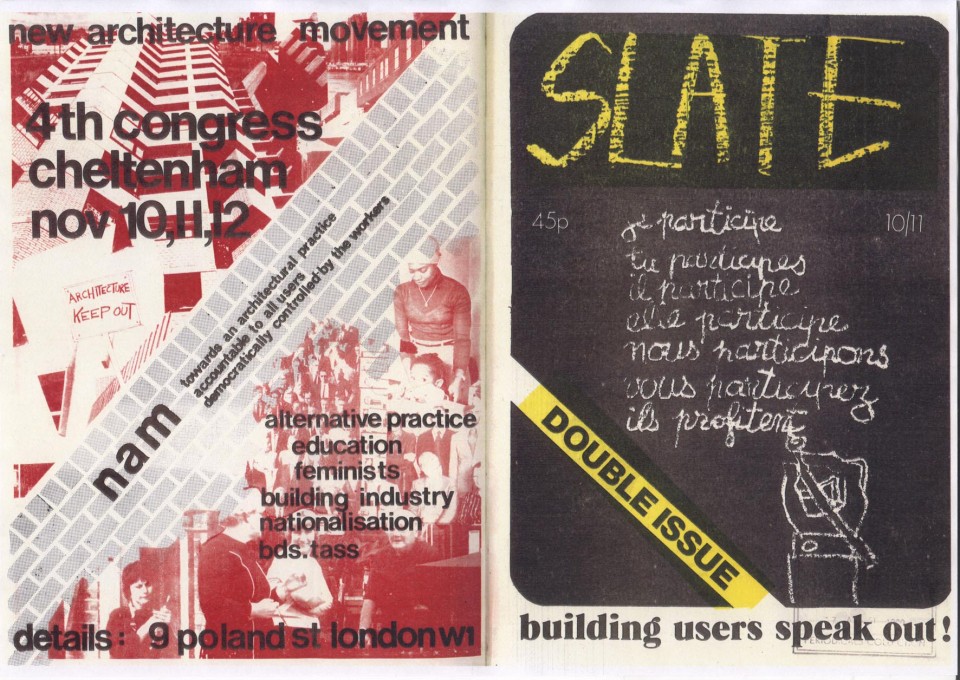

Interestingly, there are some important historic precedents from within the UK architectural profession to draw upon. During the 1970s, the Architects Revolutionary Council (ARC) and the New Architects Movement (NAM) were already coming to see the RIBA as incapable of either supporting workers or promoting high ethical standards. Instead, they called for a new, sole architectural union. NAM published a magazine called SLATE, which provided a discourse on ethical concerns such as gender in architecture, architectural education, and social causes. The pamphlet they published in 1977, titled ‘Working for What’, still resonates with today’s debate around union action and the need for unity in the architectural sector. It recognised that “architecture is first, and foremost, a business” and outlined the issues of the division of labour within the workplace, stating that architectural workers are not only those registered professionals, but all those employed within an architecture studio.

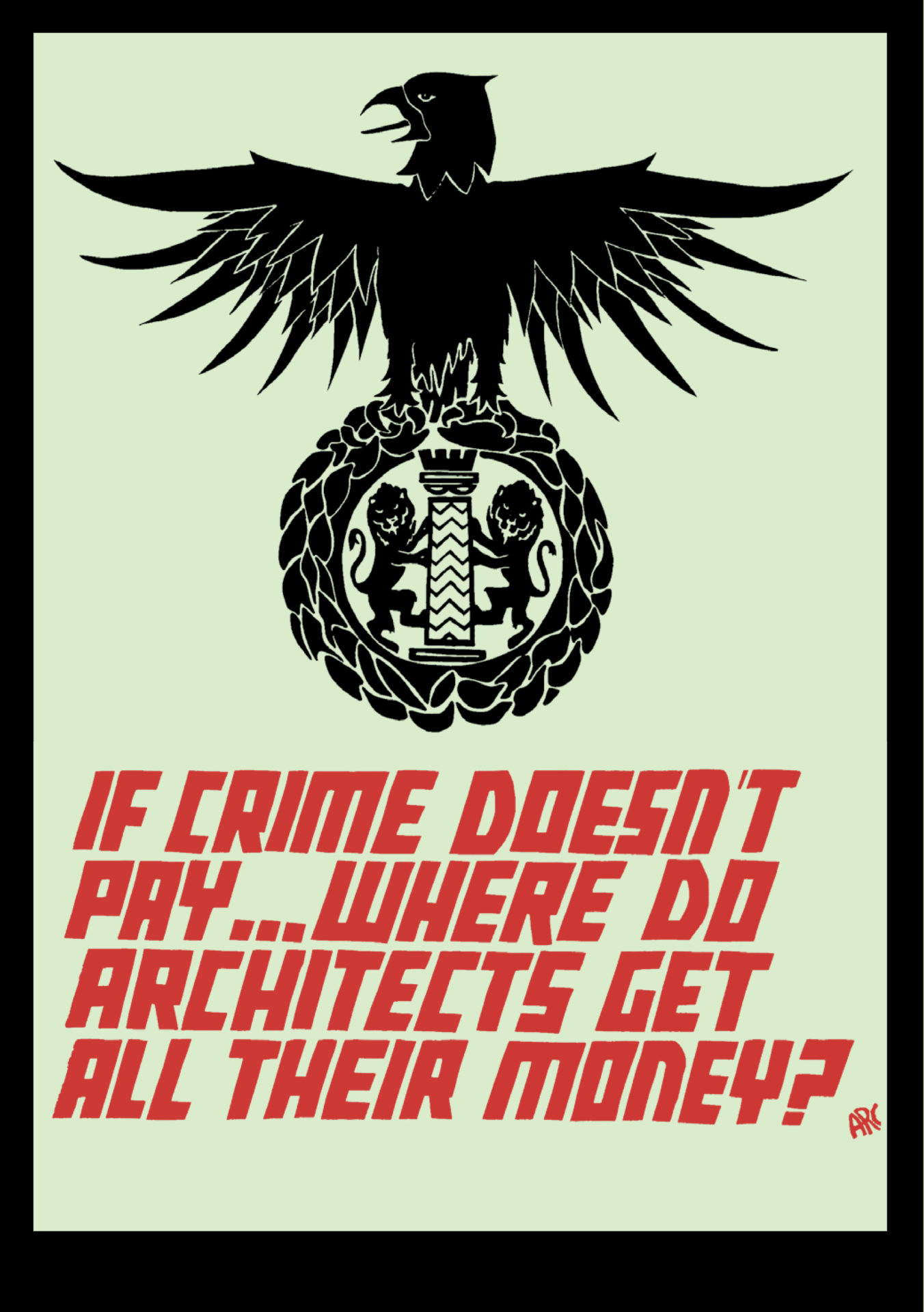

“Working for What?” cartoon from SLATE.

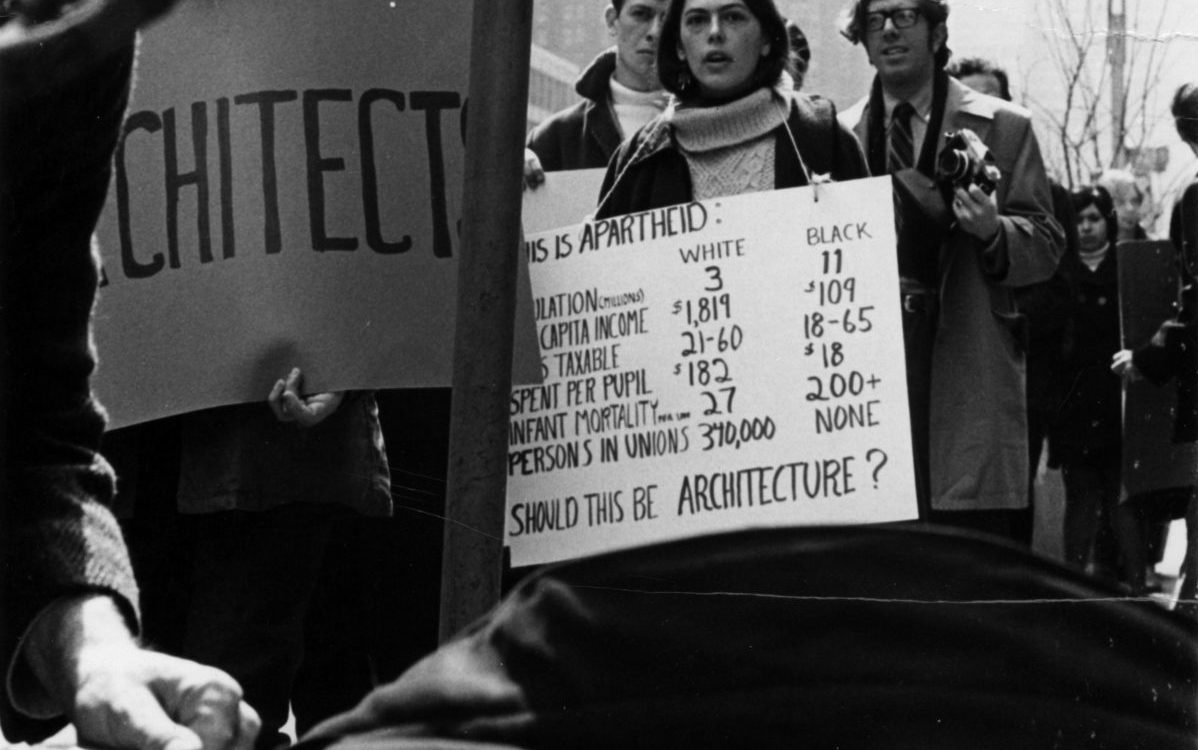

Photo by Spatial Agency.

Their calls for action included campaign demands for an architectural union: protecting jobs, salaries, reasonable working hours, reducing wage gaps and lobbying for equal opportunities in the workplace. Furthermore, NAM focused there attention beyond internal culture, questioning the politics, morals and ethics surrounding the architectural service as a whole. More than 30 years later, architects are still facing the same issues and have achieved little meaningful change.

Architects Revolutionary Council, meanwhile, was a student body led by Brian Anson during his professorship at the Architectural Association in the 1970s. One of the group’s founding members was Peter Molony, who, after leaving the AA, went on to campaign as a housing activist and became a project manager at Hackney Council, a local government authority in North West London. According to Molony, the initial impetus for the ARC was to raise the ethical standards of architectural practice. This includes the internal treatment of staff and the inhabitants of design projects. He believed it was ARC’s role to promote and prioritise these issues, as architecture is for him “potentially the most influential medium for the betterment of people’s lives… I didn’t consider it architecture, I considered it community action work”.

Despite these efforts, neither the ARC nor the NAM were ever able to establish a formal union. Since then, the arrival of new forms of work has led to the emergence of new challenges for workers. In recent years, industry work in the U.K. has been steadily declining in accordance with the transition to post-fordism (specialised, automated and flexible production).

Book covers from SLATE.

Photo by Spatial Agency.

The specialisation of labour and consequent creation of more hierarchies in the workplace has also led to an increasingly fragmented and divided workforce. Architecture offices today have a myriad of individual workers in different roles: the design-team alone can have five different kinds of architectural professional working on one project, and that’s without considering the many other support staff, such as marketing, human resources, front of house and any premises workers, who contribute to the business. While interpersonal divisions are a bad reason to accept poor working conditions, this extreme fragmentation between different roles may well be one of the factors preventing architecture workers from standing united in their demands.

And yet, earlier this year, a branch for architectural workers within Unite was successfully established by the Union of Architectural Workers (UAW). Unite is the second largest general workers union in the U.K.; the branch for architecture workers, called LE800, entitles members to all the union benefits, such as legal representation, claims, and employment rights. This is a huge feat, which should remind us that a job in architecture should be as regulated as other jobs in the U.K. Yet it is still not a solely-architectural organisation.

In light of this gathering momentum, Joe Kerr (one of the UAW’s founders) made a stirring call to action at the Spatial Practices debate ‘The Way We Work’ last year at Central Saint Martin’s. A union is our only instrument of change: “We can no longer leave it to the contemporary institutions and structures of the architectural industry to claim that they’re sorting it out. We have to cease debating and interpreting this issue; the point must now be to change it”.