Much like one of Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Vilnius presents itself to the traveler as a city of memories, a city of dead, a city of signs. Its cobblestone streets and winding walls contain multiple cities from the past: invisible, but lingering. Vilnius, Vilna, Wilna, Vilne, Wilno, it is impossible for a visitor to fully grasp the character of any one of them, so that today’s Vilnius captures the imagination with a feeling of being there and, at the same time, somewhere else, somewhere other. In the intricate topography and the fascinating toponymy, signs of the different identities that claimed the city over the centuries appear everywhere: Czarist buildings and Jewish street names, Soviet statues and Christian imagery, Lithuanian grand-dukes and Polish kings. Meanwhile, like other post-Soviet capitals, Vilnius seems to be looking for new meanings, new creative and commercial identities, new forms of urban participation. Arts festivals, informal protests, and urban reclamations intertwine with widespread gentrification, archistar-designed buildings and a hipsterized city apparently intended for touristic consumption.

This is all to say that Vilnius appeared to me as a heterotopia, a place defined by the juxtaposition of several spaces in a single physical location. What’s more, several places in Vilnius can be read as examples of what Michel Foucault termed ‘heterotopias of deviation’ (spaces parallel to society, such as prisons), which serve to exclude unwanted members in order to attain utopian conditions but which are also characterized by diversity, coexistence, and non-hegemonic interactions. In Vilnius, the rapid succession of conflicting ideologies that ended up stacked on top of each other often entailed the annihilation of unacceptable symbols and functions, an attempt to cancel traces of urban memory. These strategies of exclusion have turned it into a city of otherness, with an enormous potential for a new identity based on freedom and independence. Nevertheless, the current trends in Vilnius’ urban development seem to suggest that the void left by departing powers and ideologies is promptly going to be filled again with yet another power, yet another ideology.

The following examples are indicative of the groove left by history in the city’s urban landscape. Though spatially unrelated, these places share a history of exclusion, a sense of otherness, and elements of diversity. Mapping them through collages, I tried to render the coexistence of different, somehow invisible cities within Vilnius in a way that suggests their physical traces in space.

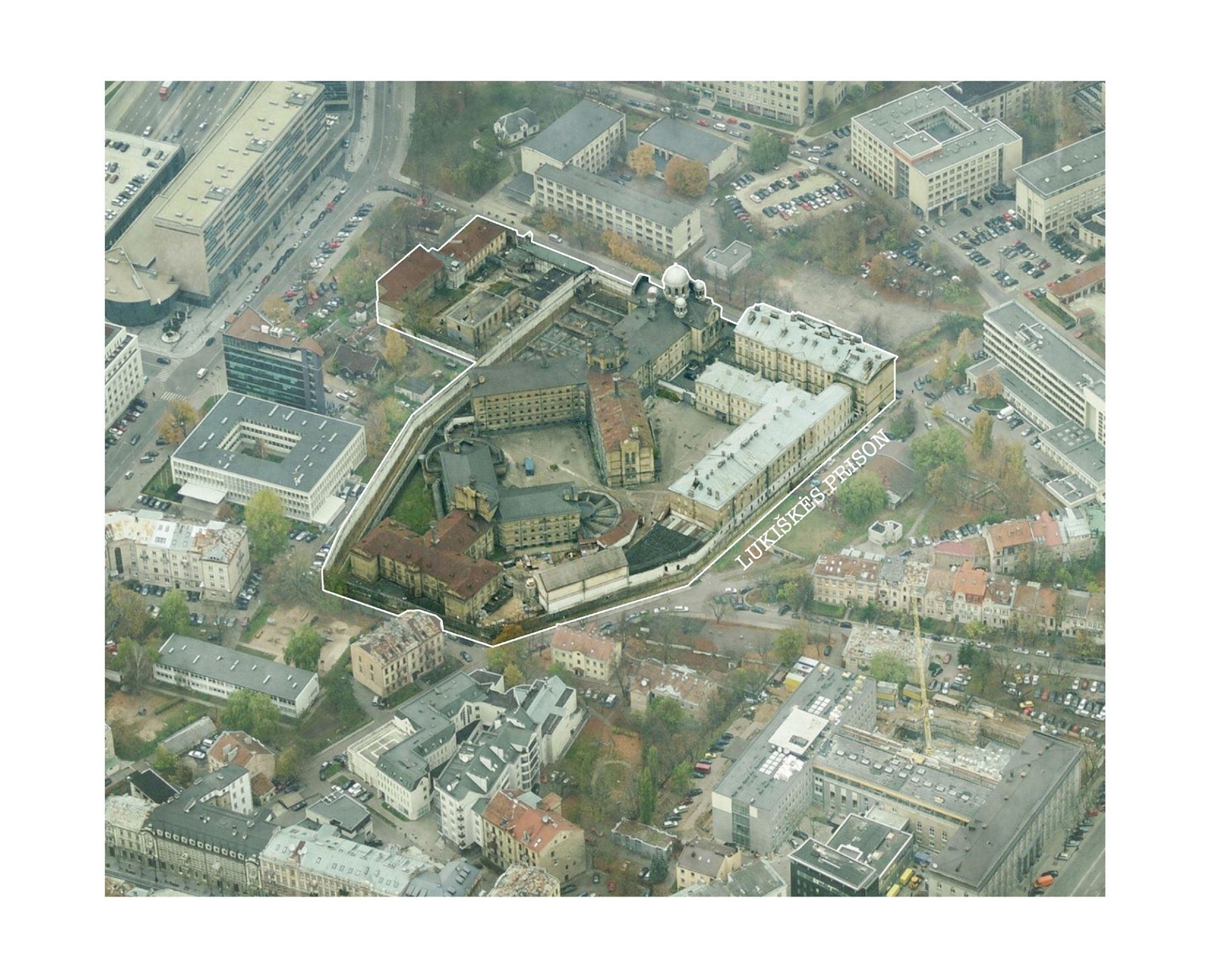

Surrounded by an unsightly wall, a prison stands in the very heart of Vilnius. Planned at the end of the Nineteenth Century, when the area was still removed from the city centre, Lukiškės Prison was completed in 1904, when the urban growth of czarist Vilnius had already engulfed the site with yellow-brick townhouses. Following the panopticon model, czarist planners designed two symmetrical three-wing buildings where the central cores were occupied by a Catholic Chapel and a Synagogue. Religious facilities also included the Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas, a detached building with a prominent position inside the complex. In his essay about the prison, Felix Ackermann explains that religion played an important role throughout the prison’s history. Not merely an instrument of re-education, religion was part of the prison’s own surveillance system: the watchmen in the two cores of the panopticon were, in fact, the rabbi and the priest.

Used time and again by different powers as a space of exclusion for political enemies, Lukiškės hosted prisoners with different backgrounds: communists and anarchists; Polish, Lithuanian, and Belarusian nationalists; Jews. Under German and Soviet occupation, the prison became a gathering point for mass deportations and executions, with death sentences and interrogations being carried out regularly on the premises. Lukiškės Prison was often at the center of political movements aimed at changing political equilibria. Now struggling to meet the standards of a modern detention centre compliant with EU regulations, the prison is said to be awaiting relocation. Rumors suggest that the complex, surrounded today by contemporary developments driven by the rising value of real estate, will be transformed into a museum about the history of Lukiskes. In Ackerman’s words, today the prison remains “a diverse place echoing the remaining diversity of the city’s inhabitants.” Its history as a hotbed for political dissent shows how a place of exclusion can have the potential for change and revolution.

The Green Bridge (Žaliasis tiltas in Lithuanian) was completed in 1952. It is the most recent attempt to connect the Vilnius centre to the district of Šnipiškės, the previous bridge having been destroyed by the Wehrmacht in 1944. The current bridge was built under Soviet rule and originally named after General Ivan Chernyakhovsky: after Lithuanian independence, it acquired the more popular name of Green Bridge, which had been in use among the population since one of the previous versions of the bridge had been painted green. The four corners of the bridge used to host statuary groups in Soviet social-realism style depicting students, peasants, workers, and soldiers. That is until 2015, when these statues were replaced by flower vases. This removal was presented as a safety measure given the statues’ decay and the municipality’s unwillingness to restore them, and it followed a long debate in Vilnian cultural circles about ways to deal with this uncomfortable heritage. One of the proposals entailed the construction of a cage around the statues.

The debate seems to have resolved into a bright yellow Audi Q2 appearing on the pedestal where two of the statues once stood, together with a large advertising banner. The historical series of destructions and reconstructions of the Green Bridge, a crucial infrastructure for the city, has given way to superimpositions of different symbolic meanings. Given the literal and metaphorical role of the bridge as a means of connection, replacing the Soviet statues with a car ad can be read as a nod to the transition from Communism to Capitalism. The void left by Soviet power has promptly been filled by the tyranny of consumerism, yet another ideology wishing to inculcate Vilnian citizens with these new values.

The history of Jewish Vilne is especially tragic and left an irreparable hole in the heart of the city. When the Wehrmacht invaded Soviet-occupied Lithuania, almost 40-percent of Vilnian population was Jewish. The new occupants established two ghettos in the old city, separated by Niemiecka Street and enclosed by wooden fences and barbed wire. After the population was decimated by several mass shootings in 1941, the situation started to stabilize, and albeit secluded, urban life continued in Jewish Vilne. Several cultural and educational institutions became spatial instruments for social exchange, providing room for art and culture, and for political resistance. When the ghettos were liquidated by the Nazis in 1943, only a few inhabitants managed to survive. With no Jews left to reclaim their property after the war, Soviet occupants destroyed whatever was left of the old town and partly rebuilt it into a modern style to accommodate unskilled migrants from Belarus and Russia. After the independence, only a few buildings were returned to their original owners under the Restitution Law. The rest was quickly sold by the city. The area underwent a restoration process after the Vilnius Old Town was included in Unesco World Heritage Sites in 1994.

A recent project to rebuild the 16th-century Great Synagogue (whose site is now occupied by a school) and turn it into real estate was highly criticized by the Lithuanian Jewish community, who considered it an attempt to exploit the religious significance of the location. The former Jewish district is now populated by charming boutiques and cozy cafes. While the city is appreciably moving forward instead of living in its past, the few plaques mentioning the history of the area don’t seem to do justice to the memory of the Jewish population. Given the current neoliberal approach to urban planning in Vilnius, it is not surprising that any attempt to restore the ghetto’s historical significance is pursued only insofar as it is profitable. At the moment, an independent project mapping the ghetto’s history seems to be the fairest and least divisive attempt to preserve its fragile urban memory.

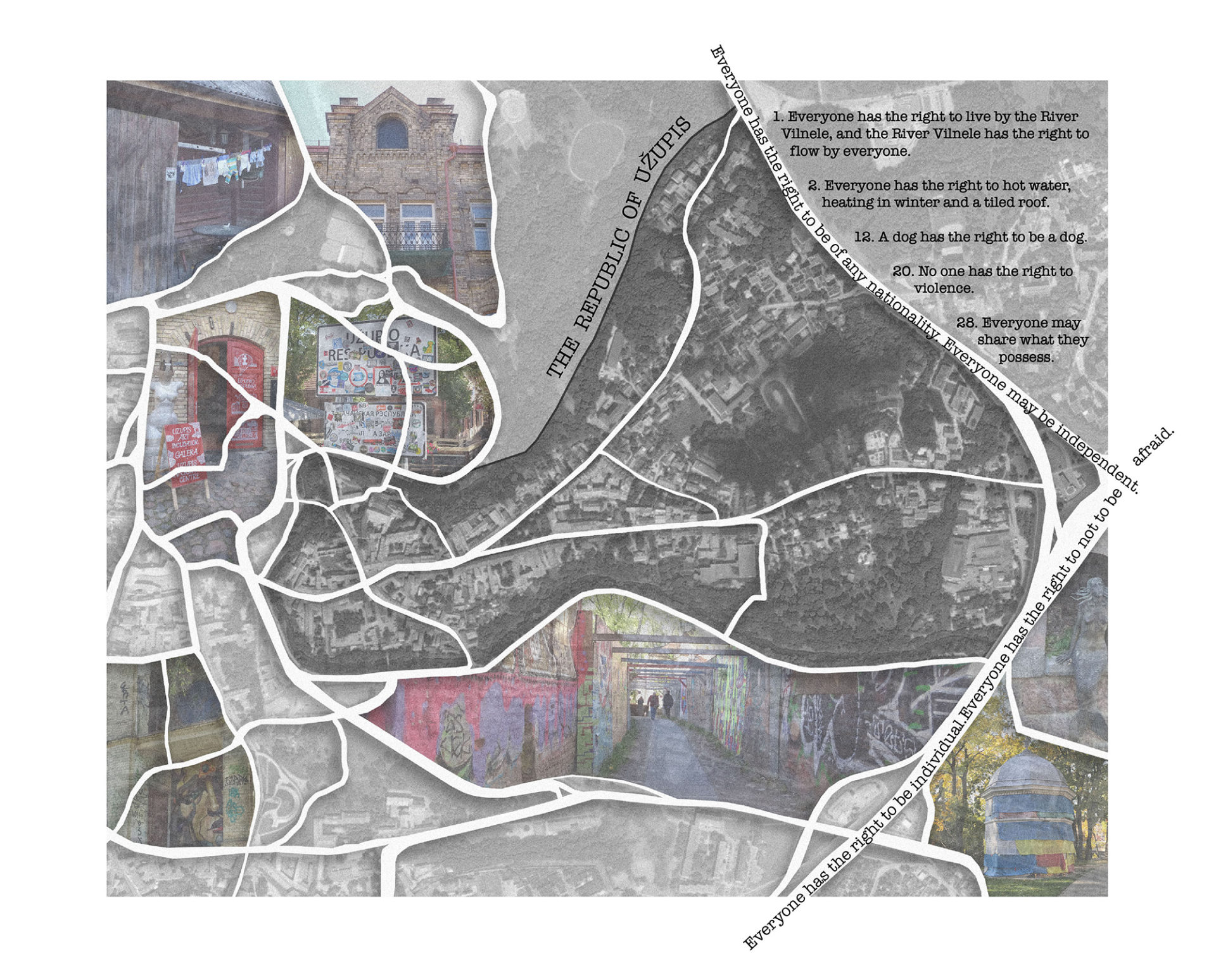

Dating probably to the 15th Century, Užupis is the oldest suburb of Vilnius and is located on a hill separated from the Old Town by the river Vilnia. In the 17th Century, the banks of the river were occupied by craftsmen who used the river as an energy source and lived in characteristic wooden houses—today a touristic sight. An analysis of urban development in Uzupis suggests that in 1981, when the Academy of Fine Arts was established in the district, the area had a seedy reputation. Inhabited mainly by ethnic minorities, it was considered a place for outsiders and misfits. Artists graduating from the Academy gradually started to take residence in Užupis, where they could squat run-down flats or rent them for very little. Although the area was becoming more charming and diverse, newcomers did not have the means to renovate the buildings and the rise of real estate prices was moderate.

In 1998, when Vilnius was swept by a climate of rebellion against the old symbols of the occupations, a few artists founded the Republic of Užupis. They drafted their own constitution, touching on human rights, references to the city’s difficult past, and quirky jokes. Over time, the district’s lively artistic program, famous honorary citizens, and thriving subcultures started to turn Užupis into a fascinating tourist destination. A new wave of residents started to move in. Counting on government-funded restoration plans and gentrification to eventually remove traces of the old ethnic minorities, entrepreneurs and professionals colonized the Republic, contributing to its current appearance as an upscale residential neighborhood. The supposedly liberal and artistic atmosphere, now confined to a few designated locations, is commodified and served to tourists in the form of expensive craft products, nordic-inspired hippie countercultures, and selected artistic projects. Meanwhile, the residents enjoy their vantage point over the city of Vilnius.

At present, a new museum designed by Daniel Libeskind is opening its doors in Vilnius. What may look as a sign of the city’s willingness to invest in culture and art, is upon further inspection indicative of how Vilnians are still struggling to have their voices heard twenty-eight years after Lithuanian independence. The new museum stands on the site of the Lietuva, a former modernist theatre built in 1950 and active until 2005. The building was for decades one of the main cultural centres in Vilnius, and after the city sold it to real estate developers, inhabitants organized several demonstrations in an attempt to save it. Yet developments carried on, and like many of the city’s other historical theatres, the cinema was demolished to make room for a new, high-profile establishment that would increase the real estate value of nearby lots. As with the other examples, the case of the Lietuva movie theatre shows how the heterotopian potential of the city has being sacrificed to a profit-driven identity all too familiar to the Western world. Despite this transformation, however, a heterotopian character still permeates the city. The frequency of urban protests in the past few years allows us to hope that the invisible cities within Vilnius are not lost forever.