When the first phase of OMA’s Norra Tornen opened in Stockholm in late 2018, I hoped these brutalist towers would be different from the increasingly corporatized work that has been coming out of the office for decades. After all, the company’s partner-in-charge, Reinier de Graaf, had made somewhat of a name for himself as the insider bad boy, the critic calling the profession out on its bullshit. This was the guy who, in his 2017 book Four Walls and a Roof, had pointed out that “the same architecture that once embodied social mobility in béton brut, now helps to prevent it”. If there was someone I’d trust not to commodify the #brutalism revival, it would be de Graaf.

At first glance, Norra Tornen’s ribbed concrete facade could easily be mistaken for postwar public housing. The buildings, superficially, check all the brutalist boxes: modular construction, monumental urban scale, and raw materiality. Though, like any good OMA partner, de Graaf used the office’s off-the-shelf combination of shape and programmatic stacking which he hides inside a facade intended to inspire a nostalgia for modernism. A quick visit to the website clearly reveals that the modernist trappings are only skin deep; what we have here is a luxury highrise in sheep’s clothing. Norra Tornen’s developer, Oscar Properties, has built a reputation converting industrial spaces into high end rentals but recently started bringing in big name architects to design new builds, such as Bjarke Ingels’ 79th & Park project also completed in 2018. In a city suffering from a housing crisis, using social housing as a veneer to sell high-end, market rate flats just seems completely irresponsible to me. The flats in Norra Tornen were sold to the few that could afford it while Stockholm’s waiting list for housing passed half a million for the first time during construction. If de Graaf is not fooling anyone, then why the grey face?

Norra Tornen in May 2020

Holger Ellgaard/Wikimedia

In an interview with Stylepark, de Graaf calls Norra Tornen “Plattenbau for the rich”. Upon reading this comment it became clear to me that the towers aren’t some clandestine attempt to smuggle the lost social ideals of modernism back into Stockholm’s luxury real estate explosion. Instead, their facades could only be a Trojan Horse, or just a virtue-signalling wallpaper, believing that co-opting socialist modernism’s concrete aesthetic would also work as a reminder of the time period that birthed it. This rebranding of midcentury architecture as contemporary luxury is closely akin to greenwashing’s cynical flattening of sustainability. Just as greenwashing reduces a progressive movement to a PR campaign to sell products, Norra Tornen’s conceptual pitch and brutalist-pantomiming design is greywashing. To greywash is to package what was once utopian as a commodity for purchase, where concrete architecture is designed to capitalise on the surging popularity of béton brut aesthetics, despite press releases that claim otherwise.

The main theme of de Graaf’s Four Walls and a Roof is that Modernism has been reduced to a style, completely divorced from its ideological tenet of human emancipation, which happens to be exactly the problem perpetuated by Norra Tornen. This thesis appears throughout the book between insider stories of academia, OMA, and how architecture, to the oligarchs and governments that fund it, is about money and power. The essays on modernism feel deeply personal, like a private journal written to grapple with deep contradictions in his life (he’s been clear about his nostalgia for the modern landscapes of his youth). At the same time, de Graaf notes in the book how modernism has always explored many other political projects as vehicles for its realization, beyond just an adherence to state capitalism and social democracy. After all, many of the Italian Futurists gladly embraced fascism under Mussolini, Le Corbusier tried to get work from both the USSR and then the Vichy regime, and Mies van der Rohe built a monument for communists Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht before courting the Nazis for work. There’s a long-established history of architects pandering to power. In the case of de Graaf, it’s hard to argue that with Norra Tornen his motivations are any different.

In Four Walls’ final essay “The Century That Never Happened”, de Graaf writes, “Once buildings are discovered as a form of capital, they can operate only according to the logic of capital. . . . Once modernism can freely be interpreted as a style rather than an ideology, it becomes relatively easy to dissociate a high selling price from a low cost base and reap record profits as a result”. The final paragraph concludes, “The same architecture that once embodied social mobility in béton brut, now helps to prevent it”. How, then, does de Graaf square Norra Tornen with statements like this? The quick answer to this is that he’s a hypocrite. To borrow an example from the nonprofit world, there’s a phenomenon of acknowledging societal problems as a means to cover one’s back, like Jeff Bezos’ Day One Fund for non-profit homelessness charities. This “commitment” fund helps Amazon appear benevolent and self-policed, while actively fighting a bill in their home city of Seattle that would have installed a head tax on companies making over $20 million in order to fund local affordable housing. The result of this maneuver is that the organization is recognized for their lofty goals while being excused for never proposing solutions to achieve them. In much the same way, de Graaf expounds impressive arguments against increasing privatization, accumulation of wealth, and outlines the way in which it chips away at architectural agency — all while doing the same thing.

Norra Tornen apartment, under construction.

Holger Ellgaard/Wikimedia

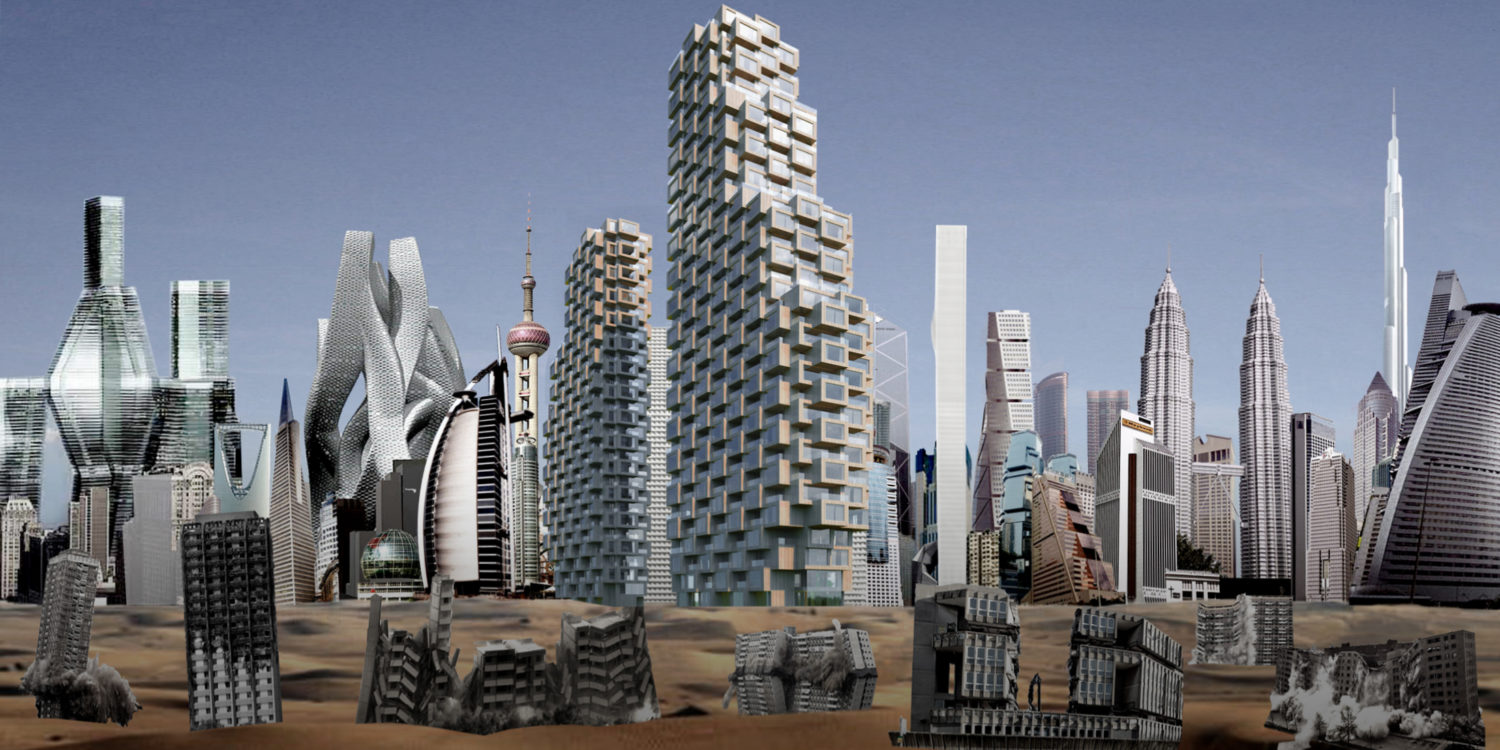

A generous reading of de Graaf is that he genuinely believes what he says and that, in order not to lose his status as a successful principal at a renowned firm, he wants to work within the system. By subliminally embedding his deeply held beliefs, and improving the perception of late modern architecture, people might actually start to look into the social policies and demand more public housing. Yet, as he himself could point out, the only outcome of Norra Tornen has been the appropriation of modernism’s aesthetics to serve capital’s ends. By promoting landmarks as desirable products for consumers and lucrative investments for foreign capital, developers stand to profit more when their projects work legibly as investment opportunities in the global real estate market than when they’re built for the people who live nearby. In the fiscal context of de Graaf’s aesthetic decisions for Norra Tornen, we see how his choice to dredge up historical forms benefits from the popularity of modernist nostalgia and “minimalist” aesthetics. It goes to show how ideologically gutted brutalism has become in an era where utopia isn’t a threat anymore but is instead window-dressing for whatever business model needs a face lift. It has been a waiting game for when the high-end real estate market would inevitably start trying to rebrand late modern concrete architecture as luxury. As writer and cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s said, “all that is solid melts into PR”.

If we leave aside Norra Tornen’s financial motivations for a moment, we see how de Graaf has awkwardly separated the object of his nostalgia from the historical-materialist trajectory, bracketing out the causal relationship of time, and leaving behind a residue of pure form. Calling de Graaf out for nostalgic indulgence is cathartic in the short term but to move beyond criticism of de Graaf’s cognitive dissonance means to trace a trajectory out of a system where nothing really changes and politics are reduced to the management of an already established, self-reinforcing system. Analyzing the paths of lost futures so that we might one day act differently is a recursive process aptly described by Fisher as “hauntology”.

In Fisher’s 2014 book Ghosts of My Life, he claims that “what’s at stake in 21st century hauntology is not the disappearance of a particular object. What has vanished is a tendency, a virtual trajectory”. Fisher calls this tendency “popular modernism“, specifically referring to the last vestiges of the UK’s paternalistic state: robust public healthcare, BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and, of course, brutalist architecture. The difference between nostalgia and hauntology is that the former flattens and inflates the past while the latter aims to resume its lost trajectories. Fisher also borrows from Frederic Jameson the concept of “nostalgia mode” which is “understood in terms of a formal attachment to the techniques and formulas of the past, a consequence of a retreat from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms adequate to contemporary experience”. In de Graaf’s Norra Tornen, modernism’s grand narrative is flattened into a commodified object — with modular construction and brutalism appearing directly in the ad campaign — making Norra Tornen a nostalgic project. The tendency for nostalgia to devolve into commodified mourning risks a cultural and political impotence to change things, as Fisher remarks in What is Hauntology?: “politics [are] reduced to the administration of an already established (capitalist) system”. As an analytical tool, hauntology looks to move beyond a critique of nostalgia, focusing instead on the process of becoming by acknowledging lost futures and moving forward. The impotence of nostalgia is pervasive. In the United States, where I’m living, and in other countries run on the degenerative logic of austerity imposed by financialization, we can’t avoid feeling it in one way or another.

As the partner in charge for a client like Oscar Properties, de Graaf was never in a position to revive the utopian ideals of early modernism. To pretend Norra Tornen will be anything other than a decorated shed obscures pure PR cynicism. De Graaf can’t escape the limitations of his work, he can’t change the consciousness of those in power who can lift them, and he can’t change architecture’s obedience to finance. Despite its apparent novelty, the blatant nostalgia of Norra Tornen is in fact anticipated by OMA’s tradition of cynically appropriating old forms to drape projects in an erudite haze of references. As with Villa dall’Ava, Casa Palestra, the Garage Museum, Parc de la Villette, or the Netherlands Dance theater, the same attitude present in Norra Tornen’s design is found: the past is something that is to be borrowed from. Personally, I’d love to see Rem’s interest in Russian Constructivism move beyond scattered footnotes and towards a commitment to a present day reinvention of our built environment — not in a novel aesthetic way that preserves existing hierarchies, but with an earnest, utopian drive to imagine a better future for ourselves. Additionally, why shouldn’t AMO be used as an actual think-tank to develop policy and post-capitalist futures?

Four Walls and a Roof ends with a 31-page photo essay chronicling the destruction of late modern social housing titled In Memoriam, depicting these buildings at various moments in their collapse. When asked whether the photographs signal a failure of architecture to achieve a better world he responded that “it is an open question if it is really the architecture that has ‘failed’ or whether the demolition of these buildings ultimately sounds the death knell of political ambitions – that when it comes to progressing in solidarity, we have simply stopped trying”. His observation is apt but it’s unacceptable for Norra Tornen to be an example of the profession “trying”. In the end, just as Trellick Tower’s once-public, now-private flats are going for three-quarters of a million pounds, de Graaf’s towers echo the same ideological perversion, even though they have been built from the ground up. If architects and designers are to redpill the profession out of its impotence, hauntology’s focus on becoming might be a method to go farther than personal nostalgia projects which result in the reduction of the subject of its mimesis to a greywashed pitch deck for the sales of luxury flats. That is, don’t conflate the future with past visions of it — and maybe don’t disregard political power, either.